Beauty in Decomposition: The Environmental Message of Compost

By David Strunk

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

R ot. Spoil. Decay. As the saying goes, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but what is perceived as beauty isn’t always easy to discern. Rot. Spoil. Decay. Close your eyes. Isn’t what comes to mind as you envision those three sharp words more often than not associated with disgust? A lingering foulness, perhaps? For me, it’s the hoard of rats that live in the trash cans in front of my downtown apartment building. Scurrying and squeaking, they catch my attention—running amok in the ruins of discarded dinners—basking in the spoiled, rotting, and decaying remains of this week’s old fruits and vegetables.

Artist and scientist Carll Goodpasture does not subscribe to the same negative connotations that I had previously held. Goodpasture’s series of photographs, Compost, is made up of over 350 images of decaying fruits, vegetation, and dead animals. The inspiration behind the number of pictures is a connection to the protest group 350.org, founded by activist author Bill McKibben. The name “350” derives from the ideology that for the planet to continue to flourish, its carbon dioxide emissions must be reduced to 350 ppm. Currently, carbon emissions are in the 400s.

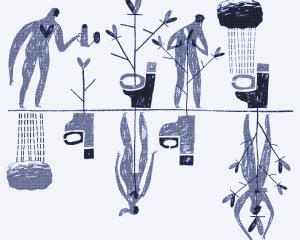

For seven straight years, Goodpasture took a photograph of his family’s compost every week. Carll calls Compost, “one family’s ‘everyday’ interactions with the natural world via consuming food, celebrating with flowers, and maintaining a garden.” The collection not only provides an unusual diary of a family’s communal fellowship but also forges acknowledgment and a relationship with what we think of as “waste.” His collection of photos requires a double take. The old food, dead mice, and dead birds appear blissfully stuck rather than on their way into the abyss. Though peace is present, the photos are also incredibly chaotic, indicating that a significant change is happening. A new phase in the cycle of life is beginning. These multi-vibrant flowers, bones, and vegetation provide a farewell victory lap for organisms that have lived their lives but can still serve a purpose. A legacy yet to be set.

Arguably, the idea of legacies is what led Carll to create Compost. After twenty years in research science, he decided he wanted to be a teacher—that it was time for him to be the one doing the mentoring. Through teaching introductory biology, Carll saw both the positive interactions that science and art could have on each other and the alarming realization of the lack of appreciation for “societal dependency on the biosphere.” Over time, Carll concluded that there is a fallacy in the belief that an intellectually informed group will make the correct decisions. Facts alone are not enough; there is still a disconnect between the reality of a fragile Earth. Art—specifically nature photography—became the empathizing answer to this problem.

Compost opens the door to a new way of encountering the living world around us. These images of decay create a unique, yet accessible path to understanding our fragile world. Looking at the compostable rot, we’re reminded of mortality, the fact that we and our world are not indestructible. But there is a silver lining: a legacy being made.

Composting is the process of creating a mixture of decomposing wastes and materials and using them as plant fertilizers to improve soil health. The sum of the ingredients in plant food is rich in beneficial organisms, including bacteria, protozoa, nematodes, and fungi. It’s a simple process of mixing green waste and brown waste and then adding it to the soil. Not only does composting combat soil-borne diseases, but it also tackles the ongoing food waste battle and helps prevent nearly one-third of food waste in America from occupying shrinking landfill space. Perhaps most importantly, composting plays a role in fighting global climate change and greenhouse gas emissions. Practicing composting in your local garden lowers greenhouse gas emissions by sequestration—removal—in the soil and preventing the usual emissions of waste by decomposing it in the soil. The lasting legacy of the spoiled vegetation photographed is not of it rotting, but of the waste being used to create anew.

Carll Goodpasture uses nature photography as a mode of expression to reveal his feelings surrounding our constantly changing planet and, at times, facilitate both concrete and ideological change. Unfortunately, Goodpasture is right when he says that correct information does not always lead to correct decision-making. But let that not deter us from the individual change we can create in our own habitats. As always, conservation begins with the individual, and composting is a great way to start—either by starting your garden or contributing to a local community program. Beginning a consistent ecological dialogue with your local environment is an important step in the fight to protect our planet. We as individuals will not always walk this Earth, but our offspring and their offspring and so on will. It is not too late to decide what our legacy as climate conservationists will be. Let us be like the rotting fruits and vegetables that I troubled over earlier and provide for our Earth in the same way she has done for us.

David Strunk is a dramatic writer based out of New York City by way of Alabama. He works with World Sensorium Conservancy as a contributing editor and producer for WS/C Kids. You can reach him here.

Plantings

Issue 38 – August 2024

Hugelkultur: Where Environmental Art Meets Permaculture

David Bacharach

The Benefits of Buying Wedding Flowers Locally

By Gayil Nalls

The Oldest Ecosystems on Earth

By Ferris Jabr

Albert the Great: Remembering a Medieval Polymath Who Paved the Way for the Renaissance and Holistic Thinking

By David Strunk

Recycling Animal and Human Dung is the Key to Sustainable Farming

By Kris De Decker

Sprouted Pumpkin Seed Salad

By Actor Matthew Modine

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.