Hugelkultur: Where Environmental Art Meets Permaculture

By David Bacharach

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

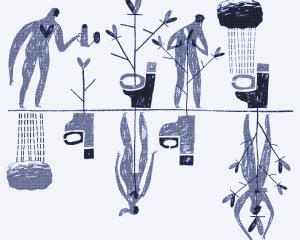

O riginating in Germany in the Middle Ages, the farming technique known as Hugelkultur has recently emerged as a beacon of sustainability in today’s fight against environmental degradation. Hugelkultur, or Hill Culture, revolves around creating elevated planting beds designed to enrich the soil and improve water retention or drainage. As an artist, I’ve reimagined this ancient technique to address urgent, present-day climate issues, weaving the utility of Hugelkultur with my statements of land art.

The Concept of Hugelkultur

Hugelkultur’s essence lies in constructing raised mounds made from logs, branches of all sizes, leaves, and other organic matter. As this material decomposes, these mounds transform into self-sustaining ecosystems that enrich the soil with nutrients, soaking up moisture and releasing it slowly, creating a thriving environment for plants. This versatile method is highly adaptable and suitable for various climates and terrains, from flat fields to steep slopes.

Embracing Invasive Flora

Over the last ten years, I have developed an application for Hugelkultur in environmental art. Utilizing only non-native, invasive plant material instead of native flora, I create land art sculptures that serve both aesthetic and ecological functions.

These sculptures, some reaching up to 100 feet long, are designed to provide people with the opportunity to process the idea of climate change visually and to raise awareness of the adverse effects of excessive greenhouse gases on the atmosphere, the pollution of our oceans with plastic, and the long-term impacts of industrialization and urbanization on the land.

The choice to use invasive plants was deliberate and impactful. Invasive species spread aggressively and outcompete native species, providing minimal benefits to local ecosystems and often eliminating native insects, plants, and animals. The environment is immediately improved by removing this invasive material, setting it aside to dry out and die entirely, and then constructing Hugelkultur mounds with it, paving the way for the resurgence of native flora and fauna. This act of removal and repurposing transforms a detrimental element into a positive force for ecological restoration and education.

The Artistic Vision

Each land art sculpture I created using Hugelkultur techniques is not merely a practical gardening project but an artistic statement that reminds us that we are working for the beauty of the natural world and our connection to it. Each sculpture, made entirely from invasive plant materials, is a testament to the transformative power of ecological awareness and action. They symbolize a commitment to long-term investment in the land, paralleling the proposed climate crisis solutions that require sustained effort and dedication.

I recently completed three such sculptures at the Irvine Nature Center in Garrison, Maryland. They are large-scale environmental art pieces that engage viewers on multiple levels. The massive scale of the mounds—up to 100 feet long and 18 feet high—commands attention and invites contemplation. They challenge the viewer to consider the impact of invasive species, climate change, and environmental degradation. By integrating art with ecological restoration, these sculptures serve as educational tools, raising awareness about the importance of biodiversity and the impact of invasive species. They encourage viewers to consider the broader implications of their actions on the environment and hopefully inspire a sense of stewardship for the planet.

Creating Art from Nature’s Materials

The process of creating these Hugelkultur mounds as art begins with the careful selection of the site and preparation of the ground. The location is chosen not just for its practicality but for its ability to enhance the visual impact of the sculpture within the landscape. Whether on flat land or a slope, careful consideration is given to the land’s natural contours, integrating the mound seamlessly into its surroundings.

- Site Preparation:

- Clear the proposed area of turf and weedy material, set aside the turf, and either dispose of invasive weeds in the trash or dry them out for future use.

- The mound can be built directly on ground level or inside an excavation, saving any removed dirt for later use.

- Base Layer:

- Use partially decomposed logs as the base layer, preferably placed parallel to the length of the mound. Trim smaller side branches for use as filler between logs.

- If immediate planting is desired, soak the first layer of woody material. Avoid slow-to-decompose trees like cedar and locust and native plant species with allelopathic properties, such as black walnut, sugar maple, black cherry, magnolia, and eucalyptus.

- Building the Mound:

- Place the previously removed turf grass-side down on top of the woody layer. Follow with tightly packed layers of leaves, grass, non-invasive weeds, straw, manure, and compost.

- Thoroughly wet these layers if immediate planting is planned, then top with 4 to 6 inches of soil.

The Transformative Power of Art and Ecology

Each layer added to the mound is a practical step in creating a sustainable garden and can also be an artistic gesture. The selection of materials, their placement, and the overall shape of the mound should be carefully considered to create a visually striking piece of land art. The decomposition process within the mound is a slow, ongoing transformation, mirroring the gradual but profound changes that effective environmental action can achieve.

The Hugel Mound’s integration with the surrounding landscape enhances its visual impact. Employing organic shapes and natural materials blends Hugel’s sculptures with the environment, creating a sense of harmony and continuity. This aesthetic integration reinforces the message of the sculptures: that human intervention can work in harmony with nature, transforming destructive forces into agents of renewal and growth.

The Science Behind Allelopathy

Understanding the interactions within plant communities is crucial to effective environmental stewardship and Hugelkultur.

Allelopathy, the chemical inhibition of one plant by another due to the release of substances that inhibit growth or germination, is an important consideration. Some native plants like those listed below employ allelopathy to create space and prosper.*

Black Cherry: Contains amygdalin.

Black Walnut: Produces juglone.

Magnolia: Releases sesquiterpene lactones.

Pine Needles: Their acidity can alter soil PH.

Invasive plants such as Callery Pear, Autumn and Russian Olive, Chinese Privet, Chinese and Japanese Wisteria, English Ivy, Multiflora Rose, Princess Tree, Tree of Heaven, Purple Loosestrife, and Yellow Iris employ a mix of allelopathy and rapid growth habits to outcompete native species, producing profound changes in native plant communities.** This process can not only eliminate native flora but also thereby harm native insects, birds, and mammals. These invasive plants can impact agricultural production, clog waterways, and burden landowners.

Practical Applications and Benefits

The practical applications of Hugelkultur extend beyond artistic endeavors. This sustainable gardening method offers numerous benefits for modern agriculture and environmental conservation:

Water Retention: Hugel mounds retain water exceptionally well, reducing the need for irrigation and making them ideal for arid regions.

Soil Enrichment: As the organic matter decomposes, it enriches the soil with nutrients, enhancing plant growth and soil health.

Climate Resilience: The increased organic matter and improved soil structure help buffer plants against dramatically changing weather conditions.

Waste Reduction: Utilizing organic waste materials, including invasive plants, reduces the need for landfill space and promotes recycling.

Hugelkultur, with its roots in ancient European farming practices, has found new life and purpose in sustainable agriculture and contemporary land art. Adapting this technique to address current environmental challenges can create resilient ecosystems, promote biodiversity, and inspire ecological stewardship.

The four 100-foot Hugel mounds I recently created are constructed entirely from invasive plants standing as powerful symbols of our ability to transform destructive forces into agents of renewal and growth. They remind us that we can build a sustainable future that honors and preserves the natural world with creativity, dedication, and a deep understanding of ecological principles. As these mounds decompose and integrate into the landscape, they will continue to nourish the earth, embodying the enduring legacy of the Hugel sculptures and their profound impact on our environment.

Sources

* Debalina Saha, S. Chris Marble, and Brian J. Pearson. Allelopathic Effects of Common Landscape and Nursery Mulch Materials on Weed Control.

Frontiers In Plant Science. 2018;9;733.

** Michaela J. Woods, Johnathan T Bauer, Dena Schaefer, and Ryan W.McEwan. Pyrus calleryana extracts reduce germination of native grassland species, suggesting the potential for allelopathic effects during ecological invasion. Biology Department, University of Dayton, Dayton, OH, United States of America. Department of Biology and the Institute for the Environment and Sustainability, Miami University of Ohio, Oxford, OH, United States of America. March, 2023.

David Paul Bacharach is a weaver of forms working with metals and materials of nature. He has been creating in his studio outside of Baltimore for the last 30 years. You can learn more about him on his website.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.

Plantings

The Benefits of Buying Wedding Flowers Locally

By Gayil Nalls

The Oldest Ecosystems on Earth

By Ferris Jabr

Recycling Animal and Human Dung is the Key to Sustainable Farming

By Kris De Decker

Sprouted Pumpkin Seed Salad

By Actor Matthew Modine