Lucy Henehan: An Interview with Co-founder of Iveragh Eco Forest

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

T his interview explores the inspiring journey of a landowner dedicated to restoring and rewilding 18.5 acres of land in South Kerry, Ireland. Through extensive research, hands-on exploration, and a deep respect for the land’s history, she has developed a unique approach to conservation.

Lucy Henehan hails from Cork, Ireland, and has made her home in Cahersiveen on Ireland’s rugged Atlantic west coast since 2000. With a long-standing career in education, she has been deeply involved in fostering learning and community engagement in the region. A proud mother of four grown children, Lucy has successfully balanced her professional life with her passion for environmental stewardship.

In April 2024, Lucy and her son, Cian Gavin, co-founded the Iveragh Eco Forest, a visionary project rooted in sustainability and conservation. Together, they acquired land in Coomastow, setting the foundation for a rewilding and a forestation initiative to restore native woodland habitats, support local biodiversity, and inspire a deeper connection between the community and the natural environment. Their collaborative efforts underscore a shared commitment to environmental restoration and the long-term health of Ireland’s unique ecosystems.

Gayil Nalls: Can you share the purpose and mission of the organization you co-founded?

Lucy Henehan: Iveragh Eco Forest is the name of the organization. Its purpose is deeply rooted in my concerns for the future, particularly about climate change, as well as my interest in restoring the land to how it once was—a much healthier and more forested state. Around 200 to 300 years ago, this entire area would have been covered in forests. Unfortunately, there is very little social record or evidence of what life was like back then, especially in the poorer rural areas. Most of what we know predates the Great Famine and coincides with the beginning of industrialization.

In the Killarney area, for example, massive oak forests were cut down to produce oak bars for the thriving barrel-making industry. This deforestation was one of the many early impacts of industrialization, and it drastically changed the landscape. Although I wasn’t born in Kerry, my family comes from the Dingle Peninsula, and I spent all my summers there growing up. That connection to Kerry is deeply personal for me.

One of my main interests in forestry stems from the belief that the land should naturally return to being forested. While this reflects a vision of the past, I also look to the future, where the challenges are equally pressing. Scientists predict that within the next 50 years, there is an increasing likelihood that the North Atlantic current system will stop running. Currently, this system brings warm ocean currents to Ireland, keeping the climate relatively mild. If you were to draw a line across the globe from here, you’d hit Hudson Bay in Canada, which freezes for several months each year. Without the North Atlantic Drift, Ireland could face a sudden and dramatic shift into much colder conditions—conditions we haven’t experienced since the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago.

Can you tell us more about the property you purchased and your goals for it, especially in light of what you just shared?

Together with my son, Cian Gavin, we pooled our life savings to make this purchase. Interestingly, the same plot of land came up for sale about 20 years ago, and I had visited it with the hope of buying it back then. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the funds at the time. This time, however, between my son and me, we managed to save enough. The first piece that became available was an 8.5-acre plot in Coomastow, in the Drum Killeenleagh area. We made an offer, it was accepted, and the process was finalized between April and May of this year. We’ve been landowners since then.

You’ve been working on plans for the future and wellbeing of the land. Where are you gathering your research and data to guide these decisions?

I’m building a network of resources that includes places, people, and reliable information from government sites. My journey into this research began during COVID when I started exploring eco farms and sustainable practices. At the time, I couldn’t find many examples in Ireland, but I came across several in England, Wales, and Scotland.

Last year, I took a career break for a year and spent about three months traveling around England, Wales, and Scotland with my little caravan, visiting eco farms and family along the way. Those visits were incredibly valuable—they gave me my first real, hands-on experience of seeing sustainable practices in action. They also provided me with direction and guidance for implementing similar ideas.

Online research has also played a role, but it can be overwhelming. There’s so much information available that it’s hard to know what’s credible or where to focus. Visiting these farms helped bridge that gap by offering practical insights and inspiration, which I couldn’t get just from browsing the internet.

Seeing practical applications and getting recommendations from people provided me with a wealth of information, direction, and guidance to delve further into the work of others. For example, I learned about Martin Crawford in Devon, England, who wrote an excellent book on food forestry. His work has been a major resource for me, and the references in his book have guided me to other influential figures. Martin himself was inspired by a forest gardener in England who pioneered the concept back in the 1960s and 70s, though I can’t recall the name at the moment. They successfully demonstrated how forest gardening could thrive in those conditions.

When I returned to Ireland, I discovered that a number of eco farms, villages, and communities were starting to emerge here. I’ve been following several of them on Facebook, and I had the opportunity to visit Coole Eco Community, which I think is doing some very interesting work. Most of these eco farms and villages are incredibly welcoming to anyone who’s interested in learning. They provide courses and workshops, many of which are reasonably priced, making the knowledge accessible. They also host weekend workshops and offer online resources, doing an amazing job of sharing their experiences, what works for them, and how others can implement similar practices.

Can you describe the current state of the land, including the types of plants that are on it? Also, could you share your plans and vision for its future?

The land is 18.5 acres with two beautiful mountain streams that converge into a Y shape as they flow down the slopes. The streams run along the boundaries before meeting in the middle, which is ideal for natural drainage. The property is located at the foot of a mountain, with the lower half primarily bog and the upper half consisting of heavy soil—not peat, but actual soil.

“Modern advice from agricultural and environmental experts now recommends leaving bogs undisturbed, as digging or planting in them releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide and contributes to emissions”

The bog, which is defined as land with turf a meter or deeper, poses some unique challenges and opportunities. Historically, this type of land was often planted with monoculture forestry, such as lodgepole pine. However, this practice has proven to be highly destructive, as it acidifies the soil and water, causing harm to rivers and local ecosystems. Modern advice from agricultural and environmental experts now recommends leaving bogs undisturbed, as digging or planting in them releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide and contributes to emissions.

While I haven’t finalized plans for the bog, I’m researching environmentally sensitive approaches. One possibility I’m exploring is planting native or compatible crops like blueberries or Roma berries. These thrive in bog conditions and could complement the natural balance of the soil. That said, my approach would be very minimal, avoiding intensive cultivation that could harm the bog’s delicate ecology.

Protecting the bog is a priority for me. While walking there over the summer with my son, we even spotted a couple of lizards—something I hadn’t realized existed in Irish bogs. Moments like that underscore how vital it is to preserve the natural habitat. The vision for this land is not about exploitation but about understanding and working with its unique qualities to restore and maintain its health for future generations.

The upper part of the property is intended for mixed forest, is that correct?

Yes, the upper half would have historically been farmed. It’s laid out in ancient fields, but that field structure hasn’t been used for decades—possibly 50 to 100 years. Over time, it has become overgrown and neglected. More recently, it was used for cattle grazing, specifically beef cattle, but they were far too heavy for the land and caused significant damage. I believe it’s more suited to lighter animals like sheep or goats.

Interestingly, one of my neighbors stopped to chat one day and shared a bit of history about the land. He told me that as a young boy, he used to help the old farmer who owned it. He mentioned that the land is actually better than it looks now, which gave me hope. Although it’s completely wild and overgrown at the moment, it was once productive farming land.

Admittedly, looking at it now, it’s hard to see its potential, and I’m sure some local people might think I’m a bit crazy to take on this project. But I believe we can restore and transform it. My plan is to incorporate mixed forestry, balancing restoration with sustainable land use. It will take time and effort, but I’m confident the land can thrive again.

Did you grow up with turf burning in your home?

No, I didn’t. I grew up in the city, so turf burning wasn’t part of my experience. However, there is a turf ridge on the bottom half of our land. At some point, turf was definitely cut there—you can clearly see it. The evidence is a noticeable step, about a meter high, between the untouched land and the area where turf was harvested.

Do you plan to rewild this land that was previously harvested for turf?

Yes, the land was certainly harvested for turf in the past, most likely to support the farm. If you look at the traditional layout of farms in this area, they stretch from the mountain down to the sea. Each section of the land served a specific purpose. The upper parts were used for sheep grazing in summer, the middle sections for proper grazing or crops, and the lower, wetter areas for cutting turf, which was used for fires. Farms were set up to sustain a very diverse, self-sufficient way of living. They also often had access to the sea for fishing.

It’s worth noting that turf-cutting only became common once the forests were gone. Historically, when trees covered the land, people would have used wood for fuel instead. Turf wasn’t a resource that was harvested forever; it was a response to deforestation. My intention now is to restore and rewild the land, keeping it in balance with its natural ecosystem. Instead of exploiting it further, I want to ensure its health and sustainability for the future.

With the critical need to transition from burning turf to sustainable energy sources and to restore boglands as productive carbon sinks, how do you hope to contribute to this effort?

I hope to contribute by sustainably maintaining the bog itself. My plan is to use it minimally, planting crops like blueberries or aronia berries—not native to this area but known to grow well in bog conditions—for basic family use. Beyond that, my primary goal is to preserve the bog as it is.

I also plan to introduce some trees to the bog, but very sparsely, not in the dense way you would plant a forest. From what I understand, over-planting trees in a bog can damage its delicate structure, causing it to break up and disintegrate. However, planting trees in a carefully spaced-out manner could potentially enhance the bog and support its biodiversity.

This is just my current understanding, as I still have much to learn about bogs. My approach is cautious and focused on finding a balance between minimal sustainable use and conservation, ensuring the bog remains a thriving ecosystem and an effective carbon sink.

How do you think your neighbors feel about the approaching end of burning turf as an energy source?

This isn’t necessarily about my neighbors specifically but more about South Kerry in general. I think the majority of people here have already moved on from burning turf. It’s really just a small number of older, rural residents who hold onto it, primarily as a tradition. Turf gathering is very labor-intensive, and there are easier and more efficient ways to heat your home now.

People are gradually letting go of turf-burning as generations change. But it’s not just about the turf itself—it’s about the emotional connection to having a fire in your home. I think that’s something ingrained in us, a link to our ancestors, even as far back as the Stone Age. For example, I still have a fireplace and a stove burner, but I use smokeless fuel. In the winter, there’s nothing more comforting than sitting around the fire. It’s a ritual that feels deeply rooted in our culture.

I try to use my fire as efficiently as possible. It heats my entire house and water, but I don’t use turf. In the future, I hope to use firewood sometimes from the trees I plan to grow, which would be a sustainable alternative. This way, I can maintain that connection to the fire while respecting the environment.

I think it’s very admirable that you’re conducting research to develop a mix of trees that could help mitigate the various climate scenarios we might face. How far along are you in this process? Could you share your journey?

I’ve been researching native trees for quite some time—really since I moved here. In 2005, I took a year off work to do an outdoor course that focused on exploring the local environment. It was a full-time program, from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., through all seasons, hiking the mountains and kayaking the rivers. During that time, I concentrated on studying the flora and fauna of the area, learning about what is native and what thrives here. By the end of that year, I had a solid understanding of the native species in this region.

The native trees here have been part of the landscape for about 9,000 years, adapting to fluctuating climates, including periods of very cold weather. This makes local genetic material incredibly resilient, which is why I’ve started collecting and growing local seeds. My goal is to integrate these native species into the land, alongside some trees that offer additional benefits, like food crops. For example, I’m exploring hazelnuts—specifically the cob-style hazelnuts from the UK—but I’ve heard they don’t do particularly well in this area.

A challenge I face is that most forest gardens and research have been conducted in places like southern England, where the climate and soil are quite different. I’m still in the phase of discovering what will grow well here, what won’t, and what will be beneficial for the future. For now, my approach is to plant a wide variety of tree species, focusing on local seeds I grow myself and sourcing plants from reputable nurseries, like Future Forests in Bantry.

I also plan to experiment with different trees that may provide long-term benefits. I’m considering apple trees, as well as pear trees—I have one in my garden that produces an incredible crop, even though pear trees aren’t common here. I’d like to try buckthorn, maybe a couple of fig trees in sheltered spots, and even walnut trees. Monterey pine is another species I’m considering. This is still very much a work in progress, but I’m excited to see how these experiments evolve and adapt to the land and climate over time.

So, what is your dream when it comes to this project?

My dream is to create 18 acres of land that is truly natural and holistically balanced, where the trees work together to form a thriving ecosystem. Once a forest is established, the soil begins to heal, fungi grow, and the entire system becomes self-sustaining. I suppose I imagine something like a Garden of Eden. If I can hold onto that vision and keep working toward it, I think that’s the ultimate goal—a high-functioning, vibrant ecosystem.

I also hope it will be a space that people can visit and experience. I’d like it to be a place where people can walk around, see the natural beauty, learn from it, or simply be present. Whether they come to meditate, reflect, or reconnect with nature, I want the land to offer a sense of peace and healing. Ideally, the land will not only heal itself but also provide healing for those who spend time there.

Gayil Nalls, PhD, is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist. She is the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy and the editor of its journal, Plantings.

Lead Photograph by Gayil Nalls

*This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Watch this complete interview with Lucy Henehan on World Sensorium YouTube.

Plantings

Issue 45 – March 2025

Also in this issue:

Manchán Magan’s Memories of the Bog

By Gayil Nalls

An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz

By Gayil Nalls

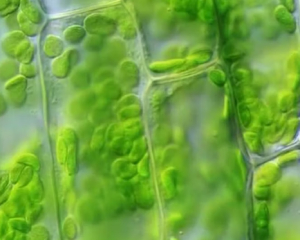

Plant Cells of Different Species Can Swap Organelles

By Viviane Callier

Przewalski’s Horses and the Ecological, Cultural, and Olfactory Significance of Dung

By Gayil Nalls

Climate change is making plants less nutritious − that could already be hurting animals that are grazers

By Ellen Welti

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Versatile Seed Crackers

By Octavia Overholse

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.