Soaking cacao seeds. Willow Gatewood

Seed Dreaming

By Willow Gatewood

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Is a seed alive? I ask my class of fourth-graders as we crowd around a long table set with an assortment of trays, rock wool, and bean seeds at different stages of germination. Most shake their heads. The small, hard ball resting at the table’s center cannot be “alive” — yet. But one child, a girl usually silent save for within smaller group activities, chimes:

“It must be. It’s waiting to be a plant.”

Discussion activates the room. As they’ve come to understand in “The Laboratory”, a science classroom turned speculative grow lab for our art workshop, Biosonic Futures, I often ask questions I never give answers for, rather allow them to discover slowly. I bring their attention back to the seed by asking: and what is it called, when a seed becomes a plant?

Germination. While several students give puzzled looks, most nod in agreement. The term germination — the process by which a seed becomes a plant — is familiar to most. Essentially, activation of enzymes reawaken metabolism and trigger a cascade of hormonal processes that lead to cell growth and root development (Understanding and breaking seed dormancy, 2023). It begins when a gentle kiss from moisture coaxes them out. Through a process of rapid water uptake called imbibition, the mung beans I soaked last night swelled with water, and today look like bubbles of soft pink flesh ready to burst. Why is it like that, it looks like slimy skin, a boy remarks as he rolls one between his fingers. Another child giggles, and I pretend not to hear her say it looks like her baby sister’s backside. This one is so soft, like a baby’s hand. The comment spurs students to examine their own skin. I’m fascinated by how quickly they draw close connection between seeds, people, and their own infancy.

After two days, the seed’s radicle, or first root formation, pokes through the softened shell. Much like an umbilical cord, this is the seed’s connection to the outside world — a way for nutrients and information to flow into its new body. My classroom fills with wonder as we return the next week to hints of green “seed leaves” poking through the shell opposite of the radicle but along the same crack that runs like a latitude line across its circumference. This is the first suggestion of the plant’s next stage, sprouting. Surprisingly, students are more excited by the white, fuzz-covered radicles that branch into roots than the actual leaves themselves. Germination is magic.

While germination and sprouting often garner more attention, the waiting phase before germination, called dormancy, is particularly interesting and also rich in information if we observe. Returning to my initial question, the stone-like bean seed exists within a fuzzy state between alive and merely the potential to be alive. Types of dormancies are as varied as plants themselves, ranging from physical, chemical, environmental, and combinations: most bean seeds undergo physical and environmental dormancy, where they wait within hard shells for the right conditions, in our case addition of water, to break (Willis, et. al. 2014). The flesh, or substance, of a seed is essentially a yolk sac and embryo, holding nutrients, enzymes, and the genetic information that allows a seed to become something else.

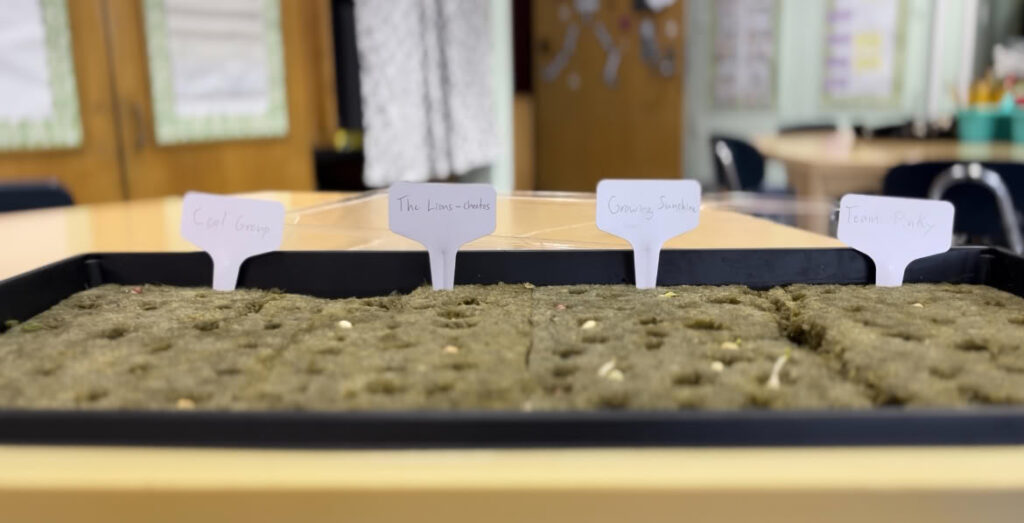

My classroom devises experiments with our dormant, germinating, and sprouting seeds. Because my workshop is both an art and science lab, we explore scientific topics in creative ways: for our seeds, we decide to represent the process of dormancy and growth sonically via biosonification, which involves turning processes within organisms into music or sound. Each class period, students connect electrodes to seeds, radicles, and shoots as the beans develop to capture biodata, which we’d built devices to convert into MIDI notes, or the musical language of computers. Soon, our seeds play pianos, gnarly synths, and even the voice of a dog. While I will not share here the entire compositions my classroom created in interest of privacy, I ran a parallel “experiment” of my own, gathering data and writing a poem from my classroom experience, in which I am always as much of a student as teacher.

While we’ve moved on to other topics, our seed trays remain the first other beings we visit when the class enters The Laboratory. Some seeds in the experiment turned to mush and molded, while others now stand as knee-height vines. We didn’t remove any seeds from our trays; rather, observed over time. Some are just now sprouting, and a flurry of excitement runs through the group. Why do we think they waited? I ask the class. We come up with theories, ranging from likely, such as lower moisture or heat than the other rows, harder shells, and smaller seeds, to simply they are shy.

No matter what stage we are in, there are lessons we can learn from a seed’s germination, but perhaps even more so from its dormancy. We remember — periods of rest and slowing down readies us for what comes next: wait, for the right conditions, and right times. Perhaps we all move through cycles of re-infancy, pliability, uncertainty: continually holding the potential to grow.

The song I share here was created with biodata collected from a mung bean seed at three different stages of development, and combined. While I chose the instrument and set my digital instruments to major, Western scale, note, pitch, and other factors that shape sound like filters are MIDI-mapped — controlled by — biodata from the seeds. In this way, it is collaboration with the process of growth over a period of five days.

Willow Gatewood is an environmental scientist, interdisciplinary artist, and storyteller from Brooklyn, NY. Follow her on Instagram: @willowg_music

Sources:

Understanding and breaking seed dormancy (2023, November 7). Agriculture Institute. https:// agriculture.institute/plant-propagation-nursery-mgt/understanding-breaking-seed- dormancy/

Willis, C. G., et. al. (2014). The evolution of seed dormancy: environmental cues, evolutionary hubs, and diversification of the seed plants. New Phytologist. doi: 10.1111/ nph.12782

Plantings

Issue 55 – January 2026

Also in this issue:

Seeds of War

By Gayil Nalls

KEW’s Millennium Seed Bank: A Mission to Save Plant Life on Planet Earth

By Gayil Nalls

The Vampire Paradox

By Lewis H. Ziska

Creating Your Own Seed Bank

By WS/C

Learning the Language of Seed

By Liz Macklin

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Rhus Juice: an Indigenous-inspired drink from the plant that connects continents

By Willow Gatewood

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.