Scent and the Male Orchid Bee: A Talk With Hsurae

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

With the new work Euglossini cologne, interdisciplinary artist Hsurae has made a case for why the new scent she has created is not merely metaphoric and why reconstructed scents are intellectual structures, really little more than a metaphor or an abstraction of what once was.

Orchid bees (Euglossini) have a unique fragrance biology— they are thought to be the only species other than humans that gather ingredients and make fragrance compositions. In decline from Mexico to Brazil, these bees are the sole pollinators of many flowers including the Vanilla Orchid. Hsurae has created a computation of the fragrance of this bee through “scientific instrumentality.” She has written, “When their ecology is dead and the species long gone, this may serve as the only memory of the orchid bee.”

We had a conversation about this work this week–

Please tell us about Euglossini cologne and what inspired you to create this work.

Even though it’s about this sense of this organic animal, it’s really about how the memory of this species can become encapsulated by scientific means, and how science tells its stories about this relationship with nature. I was very inspired by this collaborative project between Daisy Ginsberg, Sissel Tolaas and synthetic biologists, that took place at Ginkgo Bioworks in Boston.

The project “Resurrecting the Sublime” that was about reviving the scent of extinct plants?

Yes, they went through extinct species in the Harvard Arboretum and extracted DNA and analyzed it. Then they revived some of the aromatic compounds that were used to create the scent of that particular plant.

What about this scent resurrection project did you find inspirational?

I was drawn to this project because it felt like a very poetic move, trying to recreate a scent of something that’s extinct. At the same time, Ginkgo Bioworks is a biotech company, so it’s very scientific and deterministic. However, in the project, with the DNA that Ginkgo analyzed, there could be a lot of ways the different kinds of compounds could have been mixed together in any number of ratios to create the very specific scent to this plant, so the reconstruction of the flower’s smell still may be lost. What they have is a variation they came up with, even though it’s based on some sort of scientific DNA analysis, it’s just one of the million possibilities of the scent that this plant could hold that nobody living has smelled before. But the way that the story is told is that the scientists collaborating with artists have managed to revive the scent of an extinct plant species. It got me thinking about the relationship of science with nature and how it turns nature into specimens, which can only specify their value as a thing, as an object to be observed.

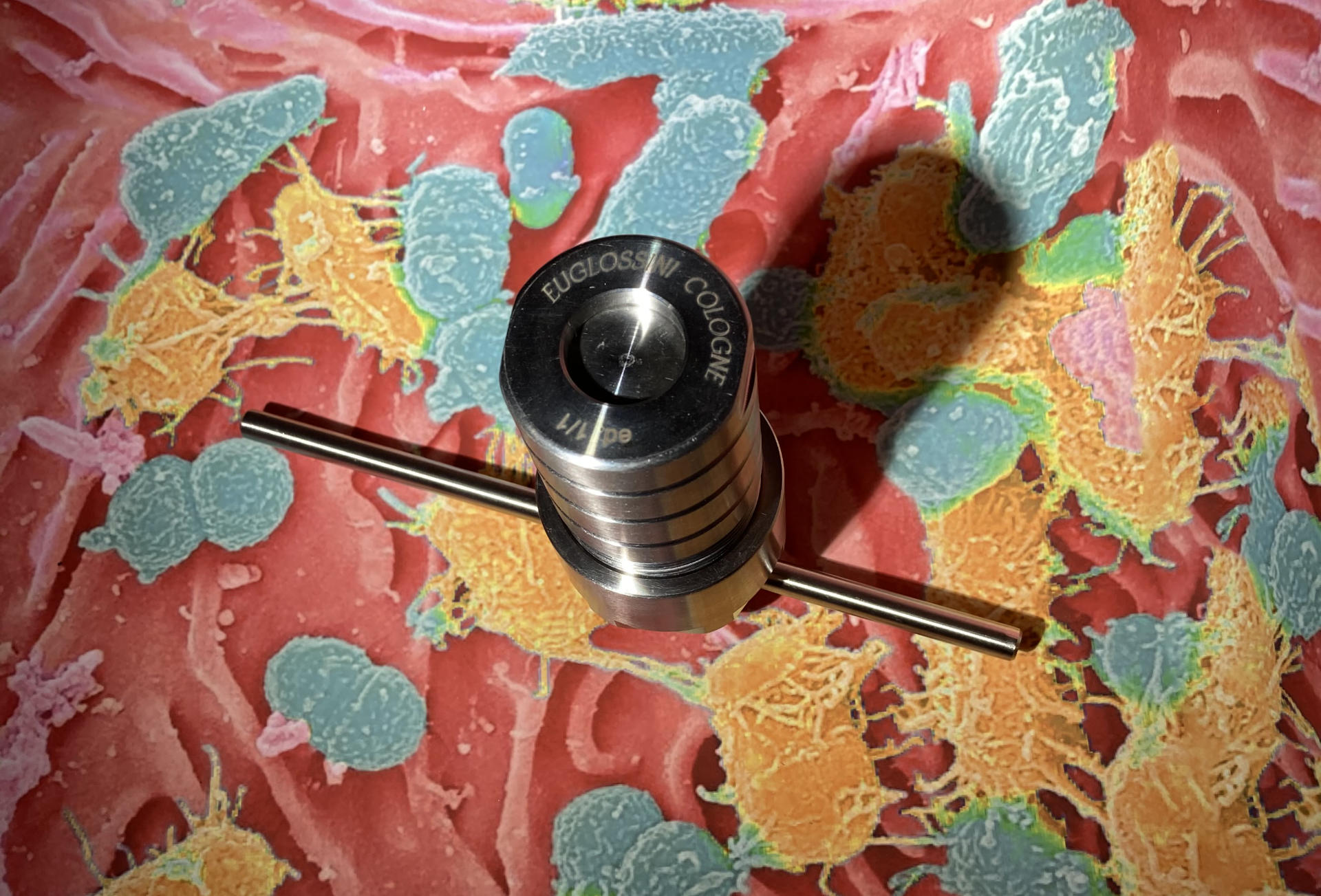

The first thing that struck me about Euglossini cologne was that the fragrance was contained in this machined, corrosion resistant, stainless-steel vault of a bottle. Can tell us about that?

I really wanted that kind of monolithic scientific authority. I wanted it to have an important presence in this scent piece. And that was the reason for the container. It is a vessel for high pressure and high temperature chemical reactions. Inside the steel is a little Teflon tub and that’s where the liquid is held. You might have noticed that there’s a key, a steel rod that goes through it to create a very tight secure encapsulation. That’s the key to tighten that seal. It gets you more leverage to really tighten it down. When you remove it, you’re not supposed to be able to open the chamber by hand. In that way, it also functions as a kind of time capsule. And so that goes with what I was saying about the timeframe of this piece.

How did you arrive at the need to preserve the smell that the orchid bee creates?

Well, I actually first arrived at bee orchid by way of the XKCD comic strip. There’s this kind of sexual reproduction replication happening in certain species of orchids that binds the bee species pollinating them to itself. Certain species of orchids rely on a specific kind of bee to pollinate them. A lot of them form these one-to-one mutual relationships. And through time, the sexual organs of these orchid flowers evolve to look like the female species of that bee that they want to pollinate them.

There was this comic strip by XKCD that is about this bee orchid. It narrates that there’s this kind of orchid, whose partner bee has gone extinct, so the only memory we have of this bee that once existed lies in the interpretation of a flower of what the genital of this kind of bee looked like. It’s quite a touching comic. The last frame stated that “the only memory of the bee is a painting by a dying flower.”

Then Donna Haraway wrote about this. So, I first came to this little anecdote through that comic strip, but then reading Haraway’s book, “Staying with the Trouble” in the chapter about sym-poiesis, which means ‘making with’, she was talking about this particular comic strip, commenting on how it’s special because it didn’t mistake lures for identity. It’s not saying that this bee orchid is exactly what the female bee’s reproductive organs look like. It is a rendering of its image through the interpretation of the flower.

I arrived at the orchid bee by chance, when I was googling bee orchid but typed it in reverse. But then I saw how these bees were really the first species in nature to create perfumes. That was the part that got me interested in orchid bees. So, I started reading more and more about them. There are many types of orchid bees. I feel like the scent they collect is really a map of the territory that they inhabit. It’s like a scent map. It’s also a lot of the bees’ agency that goes into creating their particular types of scent. I was thinking about that and reading accounts of how more and more of these kinds of bees are going extinct because their habitats are being destroyed. That’s one of the reasons why my statement for this piece is in a style that mimics that last line of the comic where it says the last memory of the extinct bee is painted by a dying flower. I was thinking about how, when all the habitats are gone and all of these species are extinct, how science might claim to recreate this ephemeral smell that they made during their lifetimes…

In Euglossini cologne,the scent compounds used in this smell are mimicking the scent traps that are used by scientists to trap orchid bees for study. It’s a synthesis of the smell through science, but it’s also an interpretation, a very human interpretation through the tools of science of what the scent could smell like, and how that serves as a more accurate memory of this species.

So, the scent that you have created is based on the hormonal chemical components that research scientists deciphered that attract the male bee? The bee’s perfume that it compiled on its body was not scientifically analyzed?

Yes. What scents they collect is dependent on which species of orchid bees they are and their particular habitat. They’re known to collect from sources that we humans find disgusting, like feces or rotten meat or rotting wood, but it’s the complexity of their perfume that really counts when it comes to mating season, and not really how pleasant smelling that perfume is. It’s that unpleasant aspect of it, but I really wanted the skatole to come out.

The work takes one into insect cognition and perception of scent, questioning the difference of scent perception in human species and insect species. What’s actually perceived as pleasant and what’s conceived as important.

What is conceived as a culturally important scent? I’ve also been reading a lot about olfactory racism and how scent is construed in the social life and how power lacks scent. When you go into institutions that are supposed to be some kind of institute of authority, like a bank or a museum, you don’t smell anything. The lack of smell is a symbol of power. And what humans find disgusting is very much conditioned through the colonial era. And so, how what we deem as pleasant and unpleasant is already racially coded, are some facets that really interest me about scents. It’s not just how good it smells or how bad it smells, but it’s all really ingrained in there.

Right. Social exposure and conditioning.

Conditioning and intergenerational conditioning also.

When did your interest in the smell and the chemical communication enter your work? Is this your most important work so far in that area?

Yes, kind of. I guess that interest developed as I was fermenting different kinds of materials. So, SCOBY is one of them. I also ferment vegetables, seafood sometimes, and it’s become a real interest of mine. And in the beginning, it was more about the material that I was interested in using, as in using in my own practice. But then in the process of fermenting these things, the scent of it really starts to impose on you. And for me, especially in New York where living space is so small and tight, I was really living in those quarters with all these different scents. And I was just really interested in this medium as its own medium of communication that we humans really don’t understand as much as we like.

I have always been interested in the scientific side of scents. My work with the SCOBY was heavily about the microbiome and how we’re outnumbered by other cells and how we can reconstruct our own sense of identity and individualism through this knowledge that we’re always more other than ourselves, like what we can see to be ourselves. And so, in all these microbiome studies, I would be drawn to scent repercussions in microbiomes. There’s always been the knowledge that, for example, we choose our partners subconsciously on the kind of scent that they emit. And we’ve never really understood why. And now there’s a microbiome interpretation of that saying that it’s this subconscious form of communication that’s not to the human, but maybe to the immune system, to the cells in the immune system or the bacteria in the microbiome of the human that communicates that this person’s microbiome and hence immune system is complimentary to your own.

So that scent that we’re drawn to is us looking, subconsciously looking for compatible immunological profiles to form partnerships with, because it maybe evolution that gave us an advantage to form family units with people whose health is complementary to our own. I approached or arrived at scent in these two very different ways. One is a very embodied, very lived-in relationship with different scents. And then the other is really more cerebral or more intellectual engagement with its scent. It all kind of came together with this new piece in the exhibition New York/New Fumes.

Considering you have this background with the biome and the fact that bacteria manufacture different volatile compounds— smells, what do you think about the idea that the bees might be collecting the types of microorganisms that they need. Bacteria produce characteristic odors.

That could be. That could very much be. Maybe they’re collecting their own little microbiomes. However, I don’t think I’ve read anything about it. I’ve read about microbiomes and bees that exist under guts, but for these orchid bees, they collect these scents into these two pouches under their hind legs and they rub them against their front legs which covers the scent compounds in lipids and fat, and stores it in that pouch. So, some sort of chemical reaction I think happens in the pouch. I’m not completely sure there is a live bacterial community inside those pouches, but it could be that maybe there’s more to what they’re collecting than just thinking of them, oh, how cute, these bees collect and make their own perfumes. Maybe it serves another kind of purpose that we don’t understand yet.

Speaking of which, I’m aware that Orchid bees do a particular performance to push the scent into the air, into the perceivability of the female. Can you tell us about that?

I’ve seen videos of this behavior and I think they all vary a little bit, so it’s not like they all do the same dance, but they all do a kind of dance with their wings and their legs that creates like a pumping motion that sprays the scent they’ve collected in their hind leg pouches into the air in front of the female during mating season.

The fact that Orchid bee courtship behavior involves creating and sharing a cologne is an interesting phenomenon.

Science understands it as a means to serve the purpose of getting the scent out in a mist form, but I like to think about it as a ritualistic dance or ceremonial dance, it gives it another dimension to be understood by. Maybe this is a spiritual experience for them. Maybe it is just pleasure. We tend to write about it as this tool they use for mating, like the Bowerbird that collects beautiful objects and makes a house out of it to impress the female. Maybe it’s more than that. Maybe there’s something to it that we don’t get, and that’s ok.

Pretty much all our observations of behaviors, especially in animals and insects, are given Darwinian-based interpretations. What are your hopes for this piece in terms of thinking about the ecological and biodiversity extinction crisis that we’re in? I felt like you were a making a big statement about chemical communication in nature and the key role pollinators play in life cycles of aromatic flowering plants. These are complex relationships. Can you talk a little bit about it?

I would hope someone would walk away from the piece with a feeling of a lack because that smell is, like I said, it could be one in a million of interpretations that’s made on what a perfume collected by an orchid bee may smell like. And so that itself is already a loss. And then to think about this scent in terms of extinction really puts it in a timeframe where the situation we’re in now might really feel like, as something that’s already bygone. If that makes any sense. I hope someone could encounter this piece and, well, be left with a chance to think about the times we’re in and what could be done to provoke some sort of emotion and then perhaps action.

That’s part of the reasons why World Sensorium/Conservancy is working conserve aromatic plants. To actually preserve the scent, we must preserve the plant. But what we are really talking about is conserving ecological communities. I felt that Euglossini cologne brings attention to the pollinators and how the symbiotic relationship between pollinators and the plants are intertwined in the survival.

The work took me to the plants are severe decline and threatened with extinction. The artwork brings attention to the fact that there’s really no way to preserve their smell yet. There is progress in chemical analysis and recreations but these really aren’t accurate- they’re high concept. We must save the plants, and the community of species that create the smells. it means also saving the ecosystems because the bacteria are often the producers of the smells and you have to save the bacteria. We need to be conserving whole ecological communities. These are very powerful and primal relationships that are jeopardy.

I completely agree. We need to be thinking about the rhizomatic connections in an ecology that interweaves into each other’s survival, instead of viewing each plant as a specimen. I was brought up with a positivist mentality, and even though I’ve come to find much joy in science, I’m also learning that there are no technofixes. It is tempting to buy into the narrative that scientists will engineer bacteria to digest plastic waste or that extinct wooly mammoths can be resurrected in a lab, but as we’ve witnessed with each case, there can be no isolated solution for a global ecological crisis. The scientific community didn’t learn about the underground mycelial wood wide web until 1997 (while sylvan communication has been described in many indigenous epistemologies), and we are slowly coming to terms with the impact that our microbial communities have on us. Our understanding of conservation needs to be as networked, grounded and interconnected as the microbial inter-glot that sustains our environments, inside and out, with or without our (scientific) knowledge.

HsuRae (Taiwanese) is an artist and educator of Bioart and endosymbiotic aesthetics. HsuRae holds a Masters of Science in Art, Culture, and Technology from MIT and currently teaches at Parsons, The New School, New York University and School of Visual Arts in New York City.

You can experience Euglossini cologne in the exhibition New York / New Fumes at Olfactory Art Keller, New York, NY, January 6 – 22, 2022.

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D., a pioneer of Olfactory Art and the creator of World Sensorium, also has a work in the exhibition.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.