ROSE

The Damask Rose in Art

Fuelling the imagination and creativity of the perfumer alone is not enough for Her Majesty the rose. Throughout history, her beauty, her scent and the symbols she gives form to have inspired all kinds of artwork: pictures, literature, poetry and cuisine. Artists adopt and reinterpret her to echo the zeitgeist of their day.

By Clara Muller

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

How can we identify the damask rose (rosa x damascena) among the thousands of varieties of roses and their myriad depictions in art?? The task is all the more complex given that the flower is so well-travelled: said to have been brought over from Persia to Europe by the French Crusader Robert de Brie in the 13th century, it has since spread and been crossed and hybridised so many times that its lineage is lost in gardens across the entire world. That’s why the art of the Middle East, its native land, is where we are still most likely to come across its voluminous silhouette.

Between the fingertips

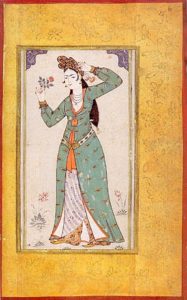

India, Lucknow, Mughal, second half of 18th century

Ubiquitous in Ottoman and Persian art across the centuries, the rose is a particularly common feature of courtly portraiture. At the end of the 15th century, several portraits by the Ottoman miniaturist Nakkaş Sinan Bey, and after him, his student Ahmed Siblizad, depict the sultan Mehmed II as aesthete, smelling either one or two roses that he holds delicately between thumb and index finger – a pose that had already been adopted by his predecessor, Mehmed I, in an anonymous miniature. The same elegant manner of holding this empress of flowers – and occasionally also carnations – can also be found in a number of portraits of Ottoman women painted at the beginning of the 18th century by the celebrated miniaturist and court artist Abdülcelil Levnî. The rose then is symbolic of beauty – moral as much as physical – and also of the intellectual refinement of its holder as well as a state of contemplation or meditation. In Islamic mysticism, the beauty, perfection and majesty of the rose makes it in effect a reflection of the divine world. This type of representation is similarly characteristic of certain Persian portraits from the Qajar dynasty (1786–1925), which notably witnessed the emergence of large oil-on-canvas paintings, pointing to the influence of European art. A splendid example from the beginning of the 19th century, now in the collection of the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, depicts a member of the harem holding a rose, pinched between thumb and middle finger, close to her face, accentuating the complexion of her cheeks. A second fresh flower is placed in the young woman’s ebony hair, set amongst pearls and jewels. But the anonymous painter did not stop there: the whole canvas is awash with roses. They proliferate in the young woman’s sumptuous outfit, adorning the white stripes of her jacket in their hundreds, as well as her black skirt. They are also among the patterns on the plate that is placed behind her, the glass that she holds in her hand and the matching carafe, decorated with a delicate spray of roses and probably containing sherbet, a drink traditionally prepared using fruits and flowers, notably water and rose petals. More than a simple portrait, the canvas appears to be a homage to the beloved flower of Persian culture, used not only in art as a symbol and a decorative motif, but also in everyday recipes for food, cosmetics and medicine.

The Rose and the Nightingale

A classic theme within the Iranian artistic tradition is that of the rose and the nightingale; set apart from the other innumerable depic- tions of birds and flowers typical to the region, to the extent that it has become an inescapable symbol of Persian culture. Known as Gul-i-bulbul, or Gol-o-bolbol, the ‘rose and nightingale’ motif, which found its earliest expression in Persian poetry, has spanned eras and art forms. The use of the motif by Persian artists in fact dates back to the pre-Islamic era and reached its zenith during the Savafid and Qajar dynasties. Taking their inspiration from literary imagery, these artists saw it as above all a romantic concept: the rose representing the desired woman, proud and unattainable amid its thorns, whilst the nightingale is the male lover who, each day, returns to sere- nade her in the hope that she lowers her defences. In most representations of the scene, the roses tower over the birds and are so imposing that the animals appear almost over- whelmed, dominated by the flowers. A different interpreta- tion, this time religious, associ- ates the rose with the Prophet Muhammad – whom it is said created the first rose from a drop of his sweat – whilst the nightingale, which is devoted to the flower, symbolises the faithful Muslim.

We can see examples of the motif in the decorative elements of traditional houses, mosques and palaces – notably in the frescoes on the walls of the Chehel Sotoun palace in Isfahan, built during the second half of the 17th century. It also appears on various lacquered objects such as chests, mirror cases, trays and pen boxes, as well as certain ceramic pieces and textiles. Frequently used to illustrate the cover of the Qur’an or illuminated books of poetry, the ‘rose and nightingale’ motif has evolved through various styles through the ages. In the 16th century, most depictions were influenced by the Chinese paintings of flowers and birds that had arrived in Persia, via a number of diplomatic gifts and imports. Later, with the influ- ence of European art and botanical studies, they tend more toward naturalism, as can be seen in the works of Mohammad Zaman and Shafi Abbasi in the 17th century, which represent some of the most remarkable examples of the motif.

A poetic and political essence

Young Ottoman lady. Ottoman miniature painting, kept at the Topkapı Sarayı Müzesi, Istanbul

The Damask rose has lost none of its evocative power in contempo- rary art. At a time when art embraces materials and formats more freely and openly than ever, Eastern and Western artists alike are no longer solely dedicated to the straightforward representation of the flower. As part of a collaborative project called Eau de Rose that Thierry Boutonnier has been running since 2013, the French artist invited residents from several neighbourhoods in Lyon to grow Damask rose bushes in unexpected spaces, then to harvest the petals and distill them to extract rosewater. The rose bushes are employed as symbols of cultural crossover, with the aim of creating shared rituals within the ‘planetary garden’ as conceptualised by the French gardener Gilles Clément, who sees the Earth as a walled garden which humans must tend to. The Dutch artist herman de vries¹, fasci- nated by plants and the beauty of nature, has created works that bring roses into the exhibition space. Between 1984 and 2015, he produced several installations consisting of vast arrays of Damask rosebuds laid on the floor. Conscious of the symbolic significance weighing it down, the artist focuses exclusively on the flower itself, presenting it in its raw form in his immense pointillist monochromes. Rising from these rosebuds strewn over the floor in their thousands, the characteristic fragrance of the flower is thought of by the artist as a silent poem.

Again, it is the flower’s scent that Habib Asal, a Swiss-Palestinian visual artist, deploys in Rainbow (2018). It is an altogether more political piece. In a stack of wire mesh shopping baskets, the artist placed seven bars of soap, one in each of the colours of the rainbow. Each is scented with Damask rose, typical of Syrian culture and much sought after in perfumery, although production of which (as with that of Aleppo soap) has been decimated by the war. The fragrance cannot be contained. Working its way through the wire mesh, it breaks loose from the apparent rainbow and diffuses like a message of hope sent by the artist to the victims of the war. Also in a political vein, Turkish artist Fatma Bucak’s work is particularly interested in the question of borders and their human consequences. In 2016, she grafted cuttings of Damask rose onto the stems of Turkish roses as part of her exhibition ‘And men turned their faces from there’ held at the David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown University in the United States. Out of 50 of these cuttings, only around 20 survived and just two or three roses bloomed – a plant-based metaphor for the migrant crisis, where so many do not survive the violence of their forced uprooting and so few manage to flourish in an unknown land. Painted, sculpted, cultivated, cut or distilled, the Damask rose has carried its majesty and the weight of its symbolism across time and borders.

¹ In lower-case, as he typically stylizes his name.

Clara Muller is a French art historian, writer, and curator, holding degrees in Literature, Art History and Museum Studies from Université Paris Diderot Paris 7, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, New York University and Columbia University.

Originally published in 2016 in

Damask rose in perfumery

Nez + LMR the naturals notebook

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.