All the Places I Have Breathed

By Caterina Gandolfi

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

G rowing up is something we all experience, yet it is hard to define what it really means. Some say that it’s about learning what’s wrong so you can discover what is right —a process of rejection that leads to wisdom. Others say that it is measured in inches: how your eyes once barely reached the table that your knees now bump into.

As someone who moved several times throughout childhood, my growth was not anchored in physical spaces. My attempts to track my height with a pencil on the walls or the sides of white closet doors were largely unsuccessful, as each house was emptied before I could outgrow the line that I had freshly marked. Most things throughout my childhood felt like they came with an expiration date, all but one. What traveled with me, clinging to the edges of overstuffed boxes in the moving truck, were my memories of scent.

The aroma of crushed rose petals reminds me of the long afternoons spent with my sisters, Anna and Margherita. We would gather around a lopsided plastic table in the garden, rhythmically mashing petals and leaves between stones. We called them potions, some more herby, some floral, some simply gross, all of which we compared proudly. Around us, the musky air would rise from the lake, its surface covered by a thick green film. That smell deepened over the years as the buildup of nutrients led to excessive algae growth in a process which I learned later is called eutrophication.

As my sisters’ and my interests shifted from potion-making to playdates and sleepovers, our parents, perhaps tired of the countless chauffeuring requests, moved us closer to the city center. The garden shrank with the move, as gardens often do as you move from rural to urban, but nature is not afraid of small spaces. Our backyard was lined with a long bay shrub, Laurus nobilis. I loved picking a single leaf, snapping it in half, and burying my nose in the sweet woody fragrance. My mother would send me out to gather herbs for dinner: bay leaves for the ragù, rosemary for roasted potatoes, sage for the ricotta and spinach ravioli. Their scent would rise with the steam from the stove and mix with the warmth of the kitchen, blanketing me in solace. These moments were already taking shape somewhere quiet, becoming part of a sensory archive I did not know I was building.

Outside of my home, other scents shaped the rhythm of daily life. On my way to school, I would chase bus number 16 down Via dei Cappuccini, lungs full of the honeyed, resinous air of Tuscan cypress trees. I never paused to appreciate the way that smell steadied me amongst the rush. I am certain that my breath would have slowed down if I had known that those trees would not be present during my mornings for much longer.

At age eleven, my parents announced that we were moving to Abu Dhabi, trading the soft green air of Tuscany for something hotter and unfamiliar. I imagined sand, skyscrapers, and heat, but could not yet picture what that air would carry. When we arrived, the sun was sharper than I could have imagined, with light reflecting off glass and pavement in ways that made it hard to look straight ahead. I often closed my eyes just to break up the glare, breathing deep through my nose and feeling the heavy air rush into my lungs, focusing on what it held. That is how the edges of this unfamiliar place began to soften: not in sight or language, but in scent.

Abu Dhabi’s thick, humid air carried smells intensely. On the High Line promenade where we lived, the soil gave off a faint, slightly sweet smell, which I later came to suspect was from fertilizer. While it was not exactly pleasant, it quickly grew familiar, becoming a reassuring scent to walk past. In the malls, beneath the marble and glass, synthetic oud clung to the air, dense, sweet, and inescapable. I was so distracted by the novelty and luxury that I did not realize how my brain was cataloguing everything, storing scent as a way of making sense.

But Abu Dhabi offered more than synthetic fragrances and fertilized earth. In this multicultural crossroads, scents became my teacher in cultural fluency. After cold afternoons at the beach, we would drive into the city and warm ourselves with karak chai served in plastic-lined cups, the cardamom, ginger, cloves, and cinnamon creating a spiced symphony that spoke of South Asian culture. During National Day at my school, the air would fill with the festive aromas of Emirati hospitality: banquets of biryani and broad beans covering long tables, with saffron and cumin dispersing across the field. In Lebanese restaurants, the sweet and fruity smell of shisha would drift through the evening air, creating pockets of social warmth.

Eventually, those markers began to add up. As the city grew more familiar, I felt taller, but there was nothing to measure against. No marked wall, no table to tell me where I started. I stopped looking for signs and let the city keep unfolding beneath me: the salty breeze of Saadiyat Beach, the powdery floral notes of plumeria blossoms, growing thick on the trees.

The scent of Arabian jasmine, Jasminum sambac, carried on a nighttime breeze. Even the heat had a smell: sun on stone, hot metal, sunscreen, and dust. What I did not understand then was how these scents were traveling directly to my limbic system, where memory and emotion live side by side, bypassing rational thought and embedding themselves as pure feeling. Before I had the words to describe Abu Dhabi, its smells had rooted themselves in me as surely as the cypress had in Florence.

Since then, I have moved again, one in a long line of moves still to come. Boxes will be packed and the closets emptied. But over the years, I have come to understand that I have grown, not just in inches or milestones, but through a quieter accumulation happening in the background. The kind stored in scent, in texture, in atmosphere. A trace of oud on the street, the sharp split of a bay leaf, and suddenly I am somewhere I did not know that I still carried. But unlike before, I now notice these moments. I pause, I inhale with attention, no longer receiving the sensory world passively, but responding to it with curiosity and care.

Growing up is not about gaining height or knowledge or even staying in one place long enough to mark it. Perhaps, it is about the accumulation of sensations carried forward without meaning to, that jolt you with memories when you do not expect it, without asking for permission. To grow up, I have learned, is to become more porous to the air and to recognize the language of scent as something worth listening to. Now, I find myself transported to places long after I have left them, not because I marked them, but because, slowly and quietly, they marked me—and I have let those sensory memories shape me.

Caterina Gandolfi holds a degree in Biology and Environmental Studies. She is passionate about using science communication to make environmental knowledge more accessible and to support meaningful change.

Top photo: https://www.flickr.com, photo by Zachi Evenor

Plantings

Issue 49 – July 2025

Also in this issue:

Aromatic Plants at the Crossroads of Fire Resilience and Risk

By Gayil Nalls

Building Biospheres: Rewilding Architecture at the Venice Biennale

By Gayil Nalls

Cool Ideas: Rethinking Air Conditioning with Sebastian Clark Koch

By Gayil Nalls

Scents, Sounds, and the Little Things In Between: A Conversation with Jenny Hval

By Ian Sleat

The Shocking Power of Bees

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

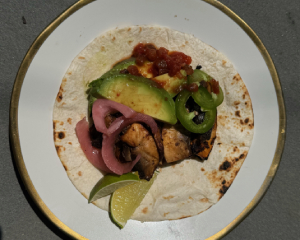

Grilled Chipotle-Lime Portobello Tacos

By Ian Sleat

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.