An Existential Reflection on Plant Intelligence

By John Steele

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

We are children of motion, of limbs, of sudden hunger and swift escape. The mind we have come to cherish—our own—is a restless one. It speaks, it reasons, it moves toward things. And so, we have made a habit of looking at the world through the lens of motion and intention. That which walks must think. That which speaks must feel. And that which does neither—well, we have called it vegetative.

Yet the greatest trick we ever played on ourselves was assuming that silence implied simplicity, and stillness, stupidity.

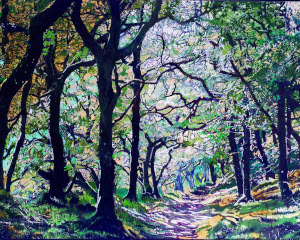

Consider the forest, not as a backdrop to life but as a stage of thought. Imagine, if you will, that buried beneath every moss-carpeted floor and within each sunlit canopy is not just photosynthesis and reproduction, but choice. Memory. Even imagination. What if, in the hush of the forest, there is thought? What if mind does not require a mouth to speak or a leg to flee?

Our philosophical traditions have long privileged motion. From Aristotle, who classified the soul in hierarchical faculties—vegetative, sensitive, rational—plants were relegated to the lowest order. They lived, yes. They drank and grew. But they did not know. And Descartes, with his strict dualism, placed mind firmly in the court of thinking matter—res cogitans—leaving all others, including animals and surely plants, as automata. The scientific revolution, for all its brilliance, inherited this legacy. Plants became green machines, their mystery dissolved in the language of mechanisms. They were marvelous biochemical factories, but mindless ones.

Even Darwin, who studied plants with love and curiosity, hesitated at the threshold. He noted that the tip of a root acts “like the brain of one of the lower animals”—a sentence that ought to have shaken the walls of biology. But it was, like so many ideas before their time, quietly shelved.

Yet the behavior of plants refuses to be still. A tree does not run from its predator, but it does, in its own way, bite back. When a giraffe chews the acacia leaf, the tree produces tannins to discourage further grazing. More remarkably, it releases ethylene into the air—a chemical signal—to warn nearby acacias, who respond in turn by pumping up their own defenses. This is not a reflex. It is a message. It is, if we dare say it, communication.

The root tips of plants navigate complex soil environments with uncanny precision. They avoid toxic substances, seek out moisture, detect the gravity vector of the Earth, and partner with fungi in vast underground symbioses. These mycorrhizal networks, as Suzanne Simard has shown, connect whole forests in webs of nutrient exchange and information flow. Dying trees, she found, may pass their remaining sugars to kin before they fall. Saplings in shade receive carbon subsidies from their elders. The forest, it turns out, behaves not as a collection of individuals but as a community.

And what of memory? The mimosa plant, Mimosa pudica, folds its leaves when touched. This is a reflex, we are told. But when researchers repeatedly dropped the plant in a way that caused no harm, it learned to stop closing its leaves. It had, in effect, learned that the stimulus was safe. That memory, astonishingly, lasted for weeks. With no neurons. No brain. But a trace of experience retained. This is not memory as we know it, but it is memory just the same.

To speak of existential intelligence in plants is to enter a deeper current. Existentialism, as a human philosophy, is concerned with agency in a world without fixed rules. It is the drama of choice, of living authentically under uncertainty. Now, it would be absurd to claim that a sunflower ponders the absurd. But a seed, landing in unknown soil, must indeed make choices. Shall it sprout now, or wait? Shall it grow upward toward light or outward toward stability? Shall it invest in root or leaf? The seed does not possess a plan. It possesses, instead, a capacity for inference. It must read its environment and act accordingly. It chooses, in the most essential sense of that word.

We tend to equate intelligence with centralization—with brains, cortex, command centers. But plant intelligence is decentralized, diffuse, and embodied. Each cell of a plant is aware of its local environment. The root apex is particularly rich in receptors. Chemical gradients, calcium waves, electric pulses—these are the currencies of vegetal information. A plant has no central node, and thus no point of catastrophic failure. It is a distributed computation. A parliament rather than a throne. And as any computer scientist will tell you, distributed systems are often more robust, if slower.

This model challenges us. We are used to minds that move. But what if mind, in one of its forms, is anchored? What if cognition need not be fast or verbal, but slow and phototropic?

From the first myths we told, there have been hints. In Genesis, the fall of man begins with eating the fruit of a tree. But the tree’s fruit gives not sustenance alone—it gives knowledge. It is not a beast who offers the gift of moral awareness, but a plant. And the story may be wiser than it knows.

Today, a growing field of “plant neurobiology”—a controversial name, to be sure—probes the limits of this possibility. It does not argue that plants have neurons. It argues, instead, that plants process information in complex and adaptive ways. That they learn. That they anticipate. That they, in their own fashion, may know.

This notion is met, as one might expect, with resistance. It disturbs our taxonomy. It troubles our ethical sleep. For if plants are intelligent—truly intelligent—then what is our obligation to them? Once, we drew moral boundaries tightly: only humans had souls. Then, slowly, we included women, the poor, other races, other species. The circle of concern expanded, always with a fight. Might the next expansion be toward the vegetal?

I do not argue for rights for roses. But I do argue for attention. For a kind of regard. For the humility to say: perhaps we are not alone in the project of interpretation. Perhaps mind, like life, takes more than one form.

In seeking plant intelligence, we do not only seek to understand plants. We seek to understand ourselves. We are asked to reflect: what is intelligence? What is memory? What is choice? Might it be that we have confused the structure of human awareness with its essence?

Consider this: plants are the original terraformers. They changed the Earth’s atmosphere, tamed the carbon cycle, invited animals onto land. In four hundred million years, they have created strategies more elegant than our best machines. If intelligence is the capacity to create and sustain a world, then surely they belong in that pantheon.

We live, I think, in a moment of great reawakening. The age of human exceptionalism is ending. Not in shame, but in revelation. For the world is not a mirror of our minds. It is a symphony, in which we are only one voice. Plants are not passive players. They are not mere green backdrop. They are, in a way that is difficult but necessary to grasp, our peers.

And so, we return to the forest with new ears. We stand in the quiet, not to impose categories, but to listen. And in that listening, we may hear a kind of thought—not our own, not even comprehensible to us—but real. Present. And deserving of wonder.

John Steele is the publisher and editorial director of Nautilus Magazine. He holds a BA in Philosophy from the University of Utah.

Plantings

Issue 50 – August 2025

Also in this issue:

Thinking Fast, Smelling Faster: Olfaction, Plants, and the Two Systems of Thought

By Gayil Nalls

The Art of Sustainability: How to Care for a Tiny Planet in a Big Universe

By Daria Dorosh

The Arborealists: Tree Painters from the United Kingdom

By Philippa Beale

Schilthuizen’s Darwin Comes to Town, and You Too Should Join Him

By Caterina Gandolfi

“Small Is Beautiful”: A Conversation with Renate Christ on Climate, Culture, and What We Stand to Lose

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Chopped Salad with Lime Dressing

By Gayil Nalls

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.