Aromatic Plants at the Crossroads of Fire Resilience and Risk

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

J uly is a month of both beauty and vulnerability. Around the world, wildfires intensify with the heat, driven by rising temperatures, prolonged drought, and expanding human development. Amid this growing crisis, a new dimension of fire ecology is coming into focus: the role of aromatic plants. Long cherished for their cultural, medicinal, and sensory significance, these plants are now being recognized as agents in how ecosystems burn, resist, and recover.

At the heart of this complexity are volatile organic compounds (VOCs), particularly essential oils, which give aromatic plants their distinctive scents. These compounds, composed of terpenes, phenols, and other VOCs, are highly flammable under hot and dry conditions. Plants such as lavender, eucalyptus, sagebrush, and trees like cedar, cypress, fir, juniper, pine, and spruce, which all contain volatile saps and resins, not only perfume the air, but also alter fire behavior in profound ways.

In fire-prone landscapes like Australia and California, eucalyptus trees have become infamous for accelerating wildfires. Their spicy, resinous oils can volatilize at relatively low temperatures, releasing combustible gases that increase ignition speed and flame intensity (Dimitrakopoulos & Papaioannou, 2001). The widely planted Eucalyptus globulus, originally introduced for timber and oil production, has transformed Mediterranean and Californian landscapes, raising wildfire risks due to its dense, terpene-rich foliage and bark (Bell, 2001; Bradstock & Gill, 2002).

Nowhere is this paradox more evident than in the Mediterranean Basin, home to one of the richest aromatic floras in the world. I recently returned from the region, where the sun-drenched hillsides and herb-scented air evoke both awe and concern. These fire-adapted landscapes, filled with rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), thyme (Thymus spp.), sage (Salvia spp.), and lavender (Lavandula angustifolia), have evolved to coexist with periodic fires. But under the pressure of climate change, their resilience is being tested.

As summers grow longer and drier, these drought-tolerant but oil-rich species contribute to a combustible landscape. The very adaptations that allow plants like rosemary, sage, and lavender to thrive under arid Mediterranean conditions, such as thick cuticles, resinous leaves, and a high concentration of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), also make them highly flammable. These VOCs can vaporize at relatively low temperatures, saturating the surrounding air with combustible gases that increase the likelihood and intensity of ignition. Dense plantings of such species can act as fuel ladders, carrying fire from the ground into the canopy and across dry terrain with alarming speed.

Yet, fire is not only a destroyer; it is also a natural force of renewal. In many Mediterranean and fire-adapted ecosystems, fire clears out dead biomass, reduces competition, and creates nutrient-rich ash beds, opening the landscape for new growth. Intriguingly, VOCs may play a catalytic role in this regeneration process. Certain aromatic compounds released during combustion can act as chemical signals that break seed dormancy, stimulate germination, or even suppress pathogens that threaten seedlings. This chemical cueing, sometimes referred to as “smoke-induced germination,” has been documented in numerous fire-prone biomes, where species have co-evolved with fire as an ecological necessity.

The challenge, then, is not to eliminate fire, but to manage it wisely, recognizing its ecological role while mitigating the increasing risks posed by climate change, land-use patterns, and the cultivation of flammable species. Designing fire-resilient landscapes means embracing fire as part of the natural cycle, guided by both ancient practices and modern science.

Across the Mediterranean, conservation efforts are turning toward fire-smart strategies. This can mean promoting drought-tolerant, less flammable aromatics like oregano (Origanum vulgare, O. onites) and myrtle (Myrtus communis), plants that thrive in harsh summer conditions while posing a lower fire risk. Another emerging approach is the use of olive groves as natural firebreaks. With their lower flammability and deep agricultural roots, olive trees can be planted strategically to slow fire spread and protect more vulnerable aromatic zones.

Equally important is the revival of ancient traditional land management practices, such as coppicing and controlled burning, once widely used across southern Europe and North Africa. These low-intensity techniques reduce fuel loads, stimulate biodiversity, and foster the renewal of aromatic understory species. They reflect ecological knowledge shaped over centuries, wisdom we would do well to heed.

To prepare for the future, regional seed banks must also be prioritized. These repositories protect the genetic diversity of local aromatic plants—many of which are endangered or microclimate-specific—ensuring that restoration efforts after fire events remain viable and culturally grounded.

It’s also vital to remember that not all aromatics pose the same fire risk. Some act as biochemical firebreaks. Succulent aromatics, like Aloe vera or moisture-retaining species of Pelargonium, resist combustion due to their thick, fleshy leaves. Others produce allelopathic compounds that suppress the growth of competing vegetation, reducing fuel buildup (Inderjit & Duke, 2003).

Emerging research suggests that some essential oils may even enhance post-fire soil health, thanks to their insecticidal and antimicrobial properties (Isman, 2000). In many Indigenous fire stewardship systems, aromatic smoke has been used to treat seeds, repel pests, and signal ecological cycles, illustrating a deeper, reciprocal understanding of fire’s role in sustaining life (Kimmerer & Lake, 2001).

Yet the global rise in aromatic plant cultivation for essential oil markets, lavender in France, frankincense in the Horn of Africa, sandalwood in India, eucalyptus across continents, calls for urgent reassessment. In fire-prone regions, agroforestry and landscape restoration must now account for plant flammability profiles, ensuring planting choices reduce rather than escalate wildfire risk.

And as climate change alters plant chemistry, the stakes rise higher. Drought stress has been shown to increase VOC concentrations, rendering even traditionally manageable species more flammable (Llusià & Peñuelas, 2000). This underscores the urgent need for adaptive conservation planning, especially in biodiversity hotspots where aromatic plants face pressures from both climate and overharvesting.

Ultimately, the case of aromatic plants at the intersection of fire resilience and risk forces us to think both ecologically and ethically. These plants carry a volatile beauty, one that can nurture or endanger, renew or destroy. They invite us to design fire-smart landscapes that are grounded in traditional wisdom, scientific understanding, and an ethic of reciprocity.

The solution is not to banish fire, but to cultivate with it, planting the right species in the right places, stewarding their renewal, and protecting the invisible threads of scent, memory, and meaning that bind us to the natural world.

Click here to view the latest global fire activity.

Fire Season Aromatic Plant Conservation Strategies by Region

Mediterranean region aromatic plant conservation strategies

Favor drought-tolerant, less flammable aromatics (e.g., oregano, myrtle)

Prune oil-rich shrubs like rosemary and thyme regularly

Create olive-based firebreaks with lower flammability foliage

Revive traditional coppicing and controlled burns

Create a seed bank of regional aromatic plants

Southwest U.S.

Replace flammable ornamental sagebrush with native fire-resilient species

Use gravel and native groundcover as buffers

Incorporate aloe and yucca into landscaping

Educate communities on VOC volatility during drought

Create a seed banks of all Southwest US species of sagebrush

Australian Bushlands

Map Eucalyptus and Melaleuca concentrations for risk zoning

Practice cultural burning with Aboriginal leaders

Encourage use of native succulents in fire-prone areas

Create community greenbelts with low-VOC species

As fire regimes become more frequent and severe, seed banking becomes a critical hedge against ecological collapse, genetic erosion, and post-fire recovery failure.

Horn of Africa

Boswellia and Commiphora are keystone aromatic species, producing frankincense (Boswellia) and myrrh (Commiphora), with deep spiritual, medicinal, and economic significance.Natural populations are in severe decline and Boswellia papyrifera populations are not regenerating in much of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Resin overharvesting, habitat loss, grazing pressure, and increasing fire events threaten natural regeneration.

Protect Boswellia and Commiphora groves through seasonal thinning

Harvest resin sustainably to avoid over-drying and fire sensitivity

Combine agroforestry with a shaded, fire-resistant understory

Even though recalcitrant or requiring treatment to germinate, establish seed banks for endangered aromatic trees

Seed Banking for Boswellia and Commiphora: Fragile Giants of the Aromatic World

These trees are keystone aromatic species, producing frankincense (Boswellia) and myrrh (Commiphora), with deep spiritual, medicinal, and economic significance.Natural populations are in severe decline and Boswellia papyrifera populations are not regenerating in much of Ethiopia and Eritrea.Resin overharvesting, habitat loss, grazing pressure, and increasing fire events threaten natural regeneration.

⚠️ Seed Biology and Conservation Challenges

Boswellia spp.

- Seeds are recalcitrant or intermediate—they lose viability quickly when dried or stored.

- They exhibit low natural germination rates in the wild (less than 20% in many species).

- Trees often reproduce poorly due to overharvesting, poor pollination, or bark damage.

Commiphora spp.

Often dispersed by animals—if those species decline, so does dispersal.

Seed viability varies widely by species.

Some species have hard seed coats requiring scarification or smoke treatment to germinate.

Gayil Nalls, PhD is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist, and the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy.

Top photo: https://pixabay.com, photo by Ylvers

References:

Bell, D. T. (2001). Ecological response syndromes in the flora of southwestern Western Australia: fire resprouters versus reseeders. The Botanical Review, 67(4), 417–440.

Bradstock, R. A., & Gill, A. M. (2002). Fire and biodiversity in semi-arid woodlands and shrublands of south-eastern Australia: functional and structural aspects. Pacific Conservation Biology, 8(2), 91–103.

Dimitrakopoulos, A. P., & Papaioannou, K. K. (2001). Flammability assessment of Mediterranean forest fuels. Fire Technology, 37, 143–152.

Inderjit, & Duke, S. O. (2003). Ecophysiological aspects of allelopathy. Planta, 217(4), 529–539.

Isman, M. B. (2000). Plant essential oils for pest and disease management. Crop Protection, 19(8-10), 603–608.

Kimmerer, R. W., & Lake, F. K. (2001). The role of indigenous burning in land management. Journal of Forestry, 99(11), 36–41.

Llusià, J., & Peñuelas, J. (2000). Seasonal patterns of terpene content and emission from seven Mediterranean woody species in field conditions. American Journal of Botany, 87(1), 133–140.

Plantings

Issue 49 – July 2025

Also in this issue:

Building Biospheres: Rewilding Architecture at the Venice Biennale

By Gayil Nalls

Cool Ideas: Rethinking Air Conditioning with Sebastian Clark Koch

By Gayil Nalls

Scents, Sounds, and the Little Things In Between: A Conversation with Jenny Hval

By Ian Sleat

All the Places I Have Breathed

By Caterina Gandolfi

The Shocking Power of Bees

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

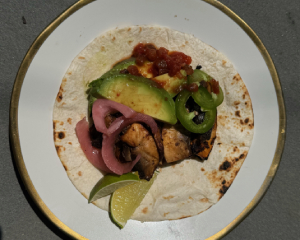

Grilled Chipotle-Lime Portobello Tacos

By Ian Sleat

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.