BREANDÁN O CAOIMH: Preserving Ireland’s Bogs– Memory, Identity, and the Path Forward

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

I reland’s bogs are more than landscapes; they are living archives of history, memory, and cultural identity. For centuries, they have shaped rural economies, provided a lifeline of warmth and fuel, and embedded themselves deeply into the collective consciousness of communities across the country. However, as Ireland transitions away from peat burning to meet climate goals, these landscapes are now at the center of a complex and often contentious debate. How can conservation efforts respect both environmental imperatives and the livelihoods of those who have stewarded these lands for generations?

In this conversation, human geographer Breandán O Caoimh offers a compelling perspective on the social, cultural, and economic impacts of this transition. A Kerry native with a lifelong connection to the land, O Caoimh has spent years researching rural development and the intersection of policy and place. Drawing on personal memories, historical context, and practical solutions, he explores how a just transition can balance ecological responsibility with rural sustainability. From the scent of turf fires to the resilience of local communities, this discussion delves into what is at stake and what the future might hold for Ireland’s bogs.

Through this dialogue, we ask: How can policy shifts honor the deep emotional and historical ties people have to the land? What role do community-driven approaches play in shaping an equitable path forward? And as turf cutting declines, what new symbols, scents, and traditions might emerge to define Ireland’s evolving relationship with its natural heritage?

Breandán O Caoimh: I am a Kerry-based human geographer, living just outside Cahersiveen—over the water, as it is locally known. I grew up on a dairy farm in East Kerry, where my brother now farms suckler cattle. My lifelong interest in the land and farming naturally led me to geography. I spent many years working in rural development before pursuing a degree in human geography, ultimately becoming a lecturer at Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick. In 2018, I established my research consultancy, focusing primarily on social research.

Gayil Nalls: How does your research, or social research more broadly, provide insight into this transitional period in Ireland, particularly in regions where turf burning has been a primary energy source and way of life for over a thousand years? As the country shifts toward sustainable energy, what do your findings reveal about the social, cultural, and environmental impacts of this transition?

Breandán O Caoimh: I’m glad you mentioned nostalgia, as well as the cultural and historical significance of peat extraction. Bogs are extraordinary landscapes—rich in biodiversity, deeply interwoven with rural economies, and integral to the identity of communities in Kerry, the Midlands, and beyond. For centuries, they have not only provided fuel but also served as places of social connection and local sustainability. In the past, when communities were more self-sufficient, we had fewer food miles, less transport, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Turf was a local, reliable energy source.

Beyond their economic role, bogs hold a special place in personal and collective memory. I recall my father’s skill with the sléan (peat-cutting spade), my preference for spreading the turf, and my grandmother’s expertise in stacking it for drying. These memories are part of my cultural identity—an experience shared by many across Ireland and in other peatland-rich regions. Recognizing this heritage is crucial, but so too is acknowledging our responsibility in addressing climate change.

Scientific research has made it clear that peat extraction contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. If we are serious about sustainability and rural livelihoods, we must strike a balance—reducing commercial peat exploitation while respecting the needs of rural communities. The transition must be managed inclusively, using more dialogue and incentives rather than punitive measures. Policies should be guided by a combination of scientific knowledge and local, tacit knowledge. In my research as a human geographer, I see the importance of bringing people along in these transitions. Communities that have long depended on peatlands must not be left behind.

What do you see as the way forward in balancing conservation and rural livelihoods?

A collaborative approach is essential. The state, private sector, communities, and landowners must work together. If farmers are restricted from selling turf, they should be compensated for lost income. Successful models already exist. For example, my research has examined the Kerry LIFE and Corncrake LIFE projects, where farmers receive compensation for adapting land use to protect biodiversity. In the case of Corncrake LIFE, farmers delay meadow mowing to allow the birds to nest and hatch, forfeiting income in the process—but they are fairly compensated. Such solutions emerge from respectful dialogue and cooperation, and a similar framework should be applied to peatland conservation.

What do you think is the greatest challenge to Ireland’s transition away from peat?

One of the biggest obstacles is Ireland’s overly centralized governance system. Decision-making is often top-down, with policies crafted in Dublin and imposed nationwide, without adequate consideration of regional differences. A more decentralized approach, as seen in many European countries, would allow local communities to develop solutions suited to their particular landscapes, economies, and traditions.

Additionally, while much attention is now given to reducing individual turf-cutting, we must acknowledge that the most significant historical exploitation of Ireland’s bogs was carried out by Bord na Móna, the state-owned peat company. Originally established during World War II to provide an emergency fuel supply, Bord na Móna continued large-scale peat extraction well into the late 20th century, even selling peat moss for gardening. This extensive extraction degraded vast carbon sinks. Now, smaller farmers and rural communities are being asked to make the largest sacrifices to compensate for past environmental mismanagement—despite having played a far smaller role in that exploitation.

A just transition must account for this historical context. The shift to sustainable energy cannot disproportionately burden those least responsible for past environmental degradation. Instead, we need policies that equitably balance ecological restoration with economic sustainability for rural communities.

What do you think the answer might be?

The answer is not singular or absolute—it is derived through process and collaboration. It is not just about the outcome, but about how we arrive at it. That process is essential. Now, that may sound like jargon, but it is true: I don’t have the full answer. I have part of it. You have part of it. The farmers in Glencar, An Dromaid and Foilmore have part of it. The people who work in the bogs, the scientists, and even the local authorities all hold pieces of the answer.

The key is to bring these perspectives together, to find the best way to protect our bogs, safeguard our environment, and sustain rural livelihoods—not just in Kerry, but in all communities facing similar challenges. That might involve reimagining the economic potential of bogs. Already, we see innovative ways of valuing natural spaces—sea swimming, forest bathing—so why not bog bathing or bog snorkeling? These kinds of ideas, and others yet to be explored, could form part of a sustainable future for these landscapes.

The historical significance of bogs must also be recognized. Designating certain bogs as heritage sites could be one way to honor their past, preserving not just the land itself but also the tools, machinery, and traditional practices associated with peat cutting.

However, preservation must be done with respect for the people who have owned and cared for these bogs for generations. If conservation measures result in a loss of income for these families, they should be fairly compensated. Biodiversity has immense value, but that value should not come at the economic expense of those who have been stewards of these landscapes for centuries.

How Can Communities Advocate for Fair Compensation?

The issue of bog conservation is just one example of a broader challenge seen across many sectors—whether it’s the spread of invasive species like rhododendrons, biodiversity conservation, fishing, land use, farming practices, spatial planning, or even the preservation of the Irish language. The principles for addressing these issues remain the same:

Community-led approaches – Solutions must be bottom-up, rather than dictated from above.

Respect for local knowledge – The insights of those who live and work in these landscapes must be valued.

Inclusive dialogue – Roundtable discussions, participatory decision-making, and collaboration between stakeholders are essential.

Investment in community-driven solutions – Once a community-led approach is established, resources and funding should follow to implement the strategies that emerge.

Ultimately, the way forward lies in fostering partnerships that ensure environmental conservation and economic sustainability go hand in hand.

What are your memories of the smell of turf? What does that evoke for you?

I can’t talk about turf without thinking of my grand-aunt Hannah. She was the one who tended the fire in my grandmother’s house. A remarkable cook and a wonderful woman, she always had the range going early in the morning. By my time, it was a closed range, but I imagine it had been an open fire before then. The turf fire not only warmed the house but also heated the oven. She would cook the dinner on the range, and then, while it was still hot in the afternoon, she would bake. Fresh bread was made every day. Fuel was used efficiently, and everything had its purpose.

In the evenings, the table—normally by the window—was moved closer to the range for warmth and efficiency. I also remember the different names for various sizes and shapes of turf. A small piece was called a ciorán, and my cousins, siblings, and I would throw them at each other in playful fights. Even turf dust had its uses.

Of course, I also remember working in the bog itself. My father was particularly skilled with the sléan, a remarkably fast turf cutter. My uncle Diarmuid had another bank nearby, and our cousins would come to work on theirs at the same time. Across the road, we could see Jack Kelleher cutting his own. The bog was more than just a place of work—it was a place where people gathered, a deeply social space.

And then there was the tea. Everyone who has worked in the bog will tell you that tea tastes different there. My grandmother would bring us tea in bottles wrapped in socks to keep it warm, sweetened heavily with sugar. We’d drink it alongside currant cakes and scones. Despite the hard labor, there was a deep sense of contentment in those moments.

Of course, turf cutting wasn’t without its challenges. The work was physically demanding, requiring constant bending and lifting. Timing was crucial—whether to cut in April or May, depending on the weather. A wet year meant the turf sat in the bog longer, exposed to the elements, while grass and rushes grew up through it, threatening to undo all the work we had done. The 1980s were particularly difficult years in that regard.

Still, despite the challenges, I look back on those times fondly. The work was hard, but the memories—of family, of tradition, of community—are deeply cherished.

These cherished memories are incredibly important. How do you think the end of turf burning will affect you personally?

Well, personally, it won’t affect me in a direct way—I burn wood now rather than turf. And I’m not farming, so I don’t depend on bogland for fuel. But I do understand the position of farmers who have bogland and have relied on local turf as their fuel source. We need to respect their perspectives, listen to them, and engage with them in meaningful dialogue.

While I fully acknowledge the science and the clear connection between turf burning and greenhouse gas emissions, we also need to recognize that turf cutting is not the sole contributor to emissions. It’s important to examine conservation in a holistic way—not just bogs, but also waterways, hedgerows, and other natural ecosystems. Bogs are one essential piece of a much larger environmental puzzle.

Exactly—since ecosystems are interconnected, they are mutually dependent. But beyond that, with this loss, Ireland also faces the disappearance of an olfactory icon, a scent deeply embedded in its cultural heritage. Is there a plant that could fill this void—one that embodies the essence of the Irish people in a similar or comparable way? What could emerge as the next significant olfactory symbol for Ireland, carrying forward its traditions and identity?

Let’s stay with the bog, and let’s stay with Heather.

Heather?

Yes.

“Heather is special because it blooms in both spring and winter. The purple and white heather flowers coincide beautifully with the golden hues of the gorse (whins).”

What about bog myrtle? It’s also a bog plant.

Absolutely—there’s no shortage of choices. Bog Myrtle is a strong contender as well. Personally, I’m drawn to Heather. That’s just my opinion, of course, but I’d love to hear what others think. Heather is special because it blooms in both spring and winter. The purple and white heather flowers coincide beautifully with the golden hues of the gorse (whins). Together, they paint the mountainsides in a breathtaking display. No artist could ever truly capture that.

Exactly—and the fragrances of these plants are equally remarkable.

Absolutely. And don’t forget the honey. Heather honey, in particular, is exceptional—rich, fragrant, and deeply tied to Ireland’s ecology. The honeybee plays a crucial role in this landscape as well.

How do you encourage people to discuss this transition openly and comfortably? One of the primary goals of this documentary is to inspire and facilitate such conversations.

We start by listening. We create spaces where people feel heard, where local voices are given priority. That’s exactly what we’re doing here this week.

Absolutely. This is essential work that must take place at the community level.

Yes, and it must extend beyond this particular issue. This approach—engagement, dialogue, and locally driven solutions—should be the model for addressing all major environmental and social challenges. We can’t sit back and wait for Dublin or Brussels to impose a one-size-fits-all solution. That simply won’t work. Each community must have the autonomy to determine what’s best for their specific circumstances.

So what do you think the next step should be after today?

We need to take stock as soon as possible, document our learnings, and build a network of everyone who participated in these discussions, whether in a large or small way. That network should continue to share knowledge and come together as systematically as possible to sustain this momentum.

While Cahersiveen is the starting point, we need to expand these conversations to other communities where bogland is deeply interwoven with the surrounding landscape—places like Glencar, Dún Géagain, and Beaufort. We must hold discussions on their terms, in their spaces, so that these communities can shape the future of their own land. That, I believe, is the way forward.

Gayil Nalls, PhD is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist. She is the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy and the editor of its journal, Plantings.

*This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Photos: Gayil Nalls

Plantings

Issue 46 – April 2025

Also in this issue:

Gardens, Greens and Reversing Alzheimer’s: A Conversation with Dr. Heather Sandison

By Liz Macklin

Growing Together

By Jake Eshelman

Viriditas: Musings on Magical Plants–Galanthus spp.

By Margaux Crump

The Perils of Early Springtime

By Theresa Crimmins

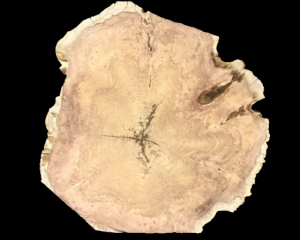

The Language of Three Rings

By Katharine Gammon

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Pineapple Rosemary Crush Mocktail

By Gayil Nalls

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.