Building Biospheres: Rewilding Architecture at the Venice Biennale

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

I

n the heart of Venice, a city suspended between water and time, the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia unfurled a theme both urgent and expansive: “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.” This year’s Biennale invites us to contemplate the overlapping intelligences shaping our world: biological, technological, and social.

Among the most quietly transformative contributions is the Belgian Pavilion, curated by Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets and Italian neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso. The project, titled Building Biospheres, is an unexpected act of cultivation that stands apart from the formal languages of global architecture. Upon entering the pavilion, from the scorching sun and dry heat, one first sees a forest below a large skylight and then experiences the wave of fragrant humidity coming from the plants.

In their hands, design becomes germinal. Soil and roots, sun and leaf take precedence over structure and spectacle. The result is a space that grows rather than asserts, a pavilion that breathes, photosynthesizes, and participates in the shared metabolism of Earth. Smets and Mancuso envision indoor environments as being generated by plants native to the climate zone in a living, self-regulating system.

Bas Smets is known for his visionary rethinking of landscape as infrastructure, designing spaces that do not merely accompany architecture but compose its living context. Stefano Mancuso, a pioneer in plant neurobiology, intelligence, and communication, understands that plants don’t simply adapt to their surroundings; they shape them. With the Belgian Pavilion, they take this insight further, inviting the indoor forest to be both an ecological installation and a philosophical provocation. Small in scale but vast in implication, it challenges how we define architecture and whether it must always be built, or whether it can arise from the innate agency of plants and the relationships between living organisms—a biome.

Building Biospheres does not display architecture; it performs it. It becomes a site of emergence, where carefully selected native and climate-resilient species are allowed to take root, exchange, and adapt. The forest is not static; it is evolving, responsive, and open-ended. Its presence shifts the role of the visitor from viewer to cohabitant, emphasizing sensory engagement, ecological intimacy, and embodied time.

The Biennale’s theme, Intelligens, suggests that intelligence is not confined to the human or the digital. It can be found in fungal networks, in the hydrologic cycle, and in seed dispersal. As a sort of atmospheric intelligence, the forest installation offers a counterpoint to the computational sublime, grounding the conversation in biocentric reality. The canopy and the mycelium, the insects and the air itself, all participate in a choreography of mutualism that outpaces even the most advanced algorithm in complexity and resilience.

In doing so, the work resonates with deep-time ecological thinking. The architecture here is the system, a biome. It asks us to think not in decades or design cycles, but in seasons, successions, and symbioses.

In a world facing compounding environmental crises, the Belgian Pavilion proposes conservation as an act of imagination and agency. Planting a forest in a cultural institution is both literal and symbolic: it models rewilding not as retreat but as reorientation, a way of seeing the land not as a resource, but as a relation, as the interconnection of living systems.

This living installation, composed of more than 200 plants, engages in conservation through cultivation, creating an infrastructure for the agency and intelligence of plants. It embodies a practice of care, attentiveness, and reciprocity, aligning with a growing global movement toward ecological restoration. The exhibition explores architecture as life-supporting microclimates through the creation of biospheres. It also functions as a seedbank of ideas, calling for multispecies design, for co-authored futures shaped not just by human needs but by the needs of the more-than-human world.

In Venice, a city itself endangered by rising seas, the gesture of replanting is profound. It asks: What if our cities could grow forests instead of burying them? What if design could protect what shelters us all?

For visitors, the forest offers more than a conceptual provocation. It is a sensory refuge, a quieting space of shadow and filtered light, and scent—mostly magnolia, which was blooming while I was there. It reminds us that our connection to the land is not only intellectual but deeply bodily. The soft, humid air, the subtle vegetal perfumes, and the gentle movement of leaves all speak to the shared atmospheric consciousness I explore along with our ongoing inquiry into olfactory and sensory heritage.

This is a pavilion that does not ask to be looked at. It asks to be withstood, to be breathed with. It insists that the future must be felt, and that its shape may be leafy, irregular, and porous.

The 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale situates us at the intersection of disciplines, timelines, and species. In Smets and Mancuso’s forest, we find a space that is a new form of architecture, one that turns inward to its most ancient impulse: to shelter, to regenerate, to participate in life’s self-sufficient cycles rather than suspend them. The forest in the Belgian Pavilion is not a metaphor. It is an active collaborator in the natural intelligence design of a livable world.

In Plantings, we have long explored how art, aromatic plants, and landscape can recover and reimagine ecological memory. This work at the Biennale expands the conversation, not with declarations, but with roots. It advances the proposition that conservation and creativity are not at odds, but are, in fact, the same generative force.

Gayil Nalls, PhD, is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist. She is the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy and the editor of its journal, Plantings.

Plantings

Issue 49 – July 2025

Also in this issue:

Aromatic Plants at the Crossroads of Fire Resilience and Risk

By Gayil Nalls

Cool Ideas: Rethinking Air Conditioning with Sebastian Clark Koch

By Gayil Nalls

Scents, Sounds, and the Little Things In Between: A Conversation with Jenny Hval

By Ian Sleat

All the Places I Have Breathed

By Caterina Gandolfi

The Shocking Power of Bees

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

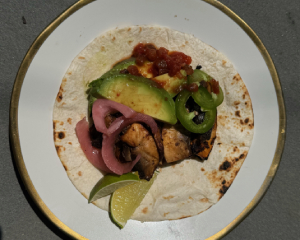

Grilled Chipotle-Lime Portobello Tacos

By Ian Sleat

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.