Jordi Cueto-Felgueroso Arocha CC BY-SA 4.0

Copal & the Day of the Dead

By Nuri McBride

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

With the success of movies like Disney’s Coco, it is clear that the English-speaking world is more familiar with Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) than ever. Overall, I think this is a good thing. Latin America, in general, and Mexico, in particular, have a lot to teach the Anglo world about culturally confronting death. Then again, the necessity to create that confrontation was born out of historical struggles rarely discussed in English coverage of the Day of the Dead. While sugar skulls and La Catrina makeup are now embedded in American Halloween, a deeper understanding of Día de Muertos still eludes many outsiders. This article goes in-depth about one aspect of this rich cultural tradition: the use of copal in Día de Muertos rituals and its history in Mesoamerica.

Incienso Americano

Copal is an aromatic tree resin central to incense making in the Americas. It has become a bit of a misnomer for many tree resins, but it is precisely the sap of the Bursera bipinnata tree. In the past, it wasn’t as easy to identify the best copal-producing trees, so a variety of sub-species were harvested, making identifying ancient specimens a bit of a pain. However, what you will find in the market today comes exclusively from the Bursera bipinnata.

These trees are endemic to Mexico and Central America, where they are found in the lush shade of tropical forests. They produce a heavy milk-like sap that dries naturally into a beautiful gummy resin. Copal can be harvested with a pocketknife, duct tape, and a plastic 2-litre soda bottle, making it an accessible source of income for rural people. These trees are also bountiful, fast-growing, and recover quickly from proper harvesting. All of this makes them ideal for long-term aromatic production.

Copal ranges in colour and quality depending on the trees sourced, their age, and any inclusions in the sap. Excellent quality resins can be found in most markets in Latin America for a reasonable price. To me, the scent is softer than other tree resins and maintains a pleasantly clean but slightly oily woodiness, with a floral, nearly lemon aspect. It reminds me of fresh-cut blonde wood. Though it does burn at twice the rate of other incense resins and tends to smoke, it is worth it for the heavenly aroma.

Copal is also called the frankincense of the Americas because it is the premier aromatic resin of the region and holds a similar historical importance in trade and religion. Copal’s use has traditionally been as incense. Its name comes from the Nahuatl word for incense, copalli. This gummy resin also has a history in traditional medicine, as a varnish, and as a glue famous for setting jade inlays into Aztec courtier’s teeth.

Though copal is a staple in the aromatic landscape of the Americas, it is rarely found in commercially produced incense. Most North American consumers are far more familiar with Indian and East Asian incense than the styles and ingredients of their continent.

Food of the Gods: Corn, Blood, and Copal

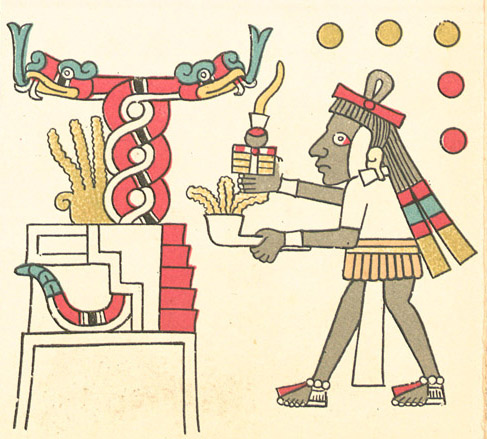

Before we can discuss the importance of copal to the Day of the Dead, we must understand the critical role copal played in pre-Colombian Mesoamerica. Its value to Aztec and Mayan cultures is evident by the effort undertaken to produce it. However, copal wasn’t for scenting one’s home; it was food for the gods.

I mean that literally and figuratively. Copal was a necessary daily sacrifice to sustain and nourish the deities in almost all Mesoamerican religions. There was a parallel between maise and copal in ancient Mesoamerica. Copal was the staple crop of the Gods, just as maise was the staple crop of humans. The nourishment of both was essential to the continuation of daily life.

Excavations in and around Lake Chapala and Nevado de Toluca show that copal was moulded into ceremonial corn cobs until the Conquest. They were even wrapped like tamales and given as offerings alongside actual maise tamales. The lake offerings (probably for the water god Tlaloc) were thrown into the water unburnt, while incense braziers discovered near the lakes would have been used to consume vast quantities of copal. Many Aztec braziers include maise in their adornments and depictions of Chicomecoatl, the Goddess of Nourishment, holding maise in her hands.

Small balls of copal found in the ceremonial well at Chichén Itzá were painted greenish blue, and some embedded with pieces of jade. The Maya had a custom of placing small lumps of jade in a corpse’s mouth to symbolise maise. This jade-maise served as spiritual food for the soul to use in the afterlife. The jade-painted copal offerings in the well may have served as a memorial food offering.

The burnt and the water offerings show two different ways ancient people used valuable aromatic materials to interact with divinity. One was a form of nourishment and shared communion; the sacrifice of sustenance made in the hopes that the gods would be pleased and share food with the people. The second was a kind of sympathetic magic. Just as they burned food for the gods, sending sustenance and prayers through ethereal fragrance, they also were creating big black plumes of smoke like the rain clouds they wanted to manifest in the world.

The connection between copal and maise was consistent throughout almost 2,000 years of Mesoamerican history. However, there was a variety of beliefs over time. The Lacandón, a Mayan people living in the modern-day state of Chiapas, believed that burning copal was akin to grinding corn. The smoke, much like the mass of corn, became spirit-sustaining tortillas for the deities. However, the idea of the spiritual tortilla was a relatively late arrival to the Maya. They used tamales (of maise and copal) as their sacrificial offering of choice until they switched to tortillas under the increased influence of Aztec culture before the colonisation period. The practice of burning copal tortillas still exists in the Lacandón belief system.

Copal also had a strong symbolic parallel with blood in the minds of ancient Mesoamericans. The movies focus on the drama of hearts extracted atop pyramids; however, Mesoamerica’s concept of blood sacrifice is more nuanced. Much like copal and maize, blood was a precious resource and a needed sacrifice to keep cosmic order. In their worldview, the people owed a blood tax to their deities, like the taxes they paid to the state.

While human sacrifice happened, animal and less dramatic types of human blood sacrifice were also involved. People drew blood with ceremonial cactus spines to enhance their pleas for divine intercession. Blood was often sprinkled on temple censers, mixing blood, copal, and maize. There is a parallel to these gestures, one pierced one’s skin to extract blood, much as one pierced the trees for resin.

The connection between blood, maize, and copal is not all ancient history either. The Mam Maya of Guatemala continues to perform a planting ritual called pomixi, or the copaling of the maise. Part of the ceremony involves participants dripping sacrificial blood from pricked fingers over copal and then burning it in censers. The aromatic smoke of blood and copal is wafted over the corn seeds before planting.

Unseen Worlds

Olfaction in Mesoamerican cosmology had an ephemeral nature that transcended planes of existence and became a way to interact with and influence the spiritual world. This type of olfactive magic was also used by the Sierra Popoluca people of Tehuantepec. The jawbone of a deer killed in a hunt was turned into a ritual object by smoking it with copal. The transubstantial and transcendental qualities of the scent tether the animal’s spirit to its remains. This tether allowed the community’s shaman to recall the deer spirit back from the spectral world to its bones and, by doing so, harness that energy to bless the community with a successful hunt.

The incredible power of aromatic substances as ritual tools is that odour is both earthly and otherworldly. It affects us emotionally and links us to our cultural and familial pasts. Copal is a tangible material, yet it creates a time and space separate from the day-to-day bustle of life.

Copal & the Church

In Mexico, copal has an ancient reputation as an intermediary substance with the divine. It was also a material associated strongly with the land and the indigenous people. As such, copal and many aspects of indigenous religions were suppressed under colonial rule. Before colonisation, the yearly celebrations to Mictēcacihuātl took up most of August. However, under Spanish control, Mictēcacihuātl was declared a demon and ceremonially exorcised from the land. The Christian festival of All Saints was promoted as an alternative.

Enormous effort was made to crush the indigenous religion. It wasn’t only a matter of Christian missionary zeal but also a means of disrupting indigenous power structures. Despite a concerted effort, the Spanish could never wholly eliminate these rituals because they never understood the catharsis they provided to the community. As Mictēcacihuātl worship was suppressed, the three-day festival of All Saints, the Day of the Innocents and All Souls Day became increasingly important and synchronised with traditional practices. So, while the observance of All Saints became sacred in Mexico, it didn’t remain wholly European and instead adapted. In time, a unique practice arose in the Day of the Dead that reflected a Mesoamerican past, colonial scars, and a synchronised future.

Copal burning would be forbidden at Church services in Mexico and Central America from the 16th century until the 1890s. While the Church was wary of copal, the people never were. Copal was and is still used as part of the region’s folk and domestic religious expression.

The Scent of the Day of the Dead

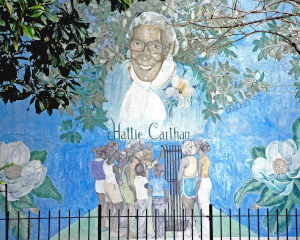

What does Día de Muertos smell like? The spiciness of the cempazúchitl (Aztec marigold) and copal. Copal is important in Day of the Dead rituals at the graveside and at family memorial altars called ofrendas.

Copal is burned graveside, in part, to create liminal and sacred space, but it also serves as an olfactory lure for the dead. Just as copal connected the spirit of the deer to its jawbone, so does it connect and pull human souls back to their bones. Copal smoke can still transverse and communicate between the material world and the world of spirits.

The ofrenda is filled with items symbolic of the hospitality due to a traveller. Salt, water, and bread are essential. Toys for children and the dead’s favourite foods, drinks, or cigarettes reinforce the personalities of the departed. These celebrations aren’t for abstract ancestors but for those that one knew and lost. Copal is burnt here too. Again, it creates liminal space and lures the spirits from the cemetery to their relatives’ homes. However, copal’s main purpose at the ofrenda is to transmogrify the material food, emotions, and prayers of the family altar into spiritual sustenance capable of nourishing the dead, just as it did when it was fashioned into tamales for the Gods.

Today most people don’t believe these things literally. However, by continuing with these traditions, people connect to the embodied history of their community. So, copal still does what it has always done. It nurtures the bond between the living and the dead.

Nuri McBride is a perfumer and writer, examining the cultural history of floral scent. She is the Program Curator for the Scent & Society lecture series at the Institute for Art and Olfaction

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.