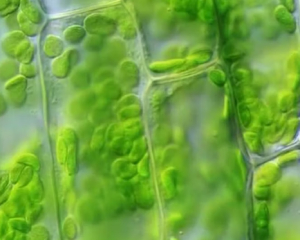

Image by Ribhav Agrawal from Pixabay

Elizabeth Grosz on Scent, Sex, and Art

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

E lizabeth Grosz, an Australian-born philosopher, is one of the most influential contemporary thinkers in feminist philosophy, known for her groundbreaking work at the intersection of philosophy, embodiment, and materiality. Her scholarship engages with the writings of key figures such as Gilles Deleuze, Luce Irigaray, and Charles Darwin, challenging traditional Western metaphysics and offering new frameworks for understanding the body, sexuality, and the lived experience.

Throughout her career, Grosz has critically examined how philosophy has shaped our perceptions of nature, time, and subjectivity, often advocating for a reconceptualization of the material world beyond human-centered narratives. Her work has profoundly impacted feminist theory, poststructuralism, and new materialism, expanding the ways we think about agency, evolution, and the political implications of embodiment. She is now the Jean Fox O’Barr Women’s Studies Distinguished Professor Emerita at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

In this interview, we delve into her lived experience with aromatic flora and get her latest reflections on philosophy’s role in addressing the body and ecological transformation at the intersection of art and aesthetics and how we might rethink sexuality, human relationships, and olfaction.

Gayil Nalls: I’d love to hear your philosophical insights on the body, sexuality, and art, the human experience, particularly connected to the sensory and material dimensions of the natural world, and how aromatic plants and the natural world engage our senses.

Can you share a personal experience where you’ve interacted with aromatic plants in a way that led to a transformative or creative experience? Let’s begin with your experiences after your surgery a few years ago, when you suddenly found yourself able to perceive a whole world of scents that had previously been inaccessible to you. How did the scent or presence of those plants influence your thinking or practice?

Elizabeth Grosz: I did indeed find that after surgery I could smell much more acutely and with more depth and nuance than ever before. It was quite a startling experience! It took some time to get used to. A few weeks ago, while I was in Australia, which has its own unique plants and weeds (and animals/ insects), I undertook a small experiment with a friend of mine. As we walked around the neighborhood, we sniffed various plants and especially their flowers, just to see what their fragrance was (if any). And the first flower we sniffed was a frangipani flower, or rather, we smelled two different species of frangipani flower, one yellow, the other red (see photo below):

What surprised me most, and I am still thinking about the implications, is that each of us sniffed both plants. I was unable to smell anything with the yellow frangipani, which my friend found most aromatic and intense. Then when we each sniffed the red one, the fragrance was overwhelming for me – a beautiful, sweet intensity – but my friend was unable to smell anything. Each of us was ‘nose-blind’ to one of these plants, although each of us found the other plant pleasantly and remarkably intense. Each of us smelled either something or nothing differently. As a philosopher, I found this fascinating: it was a simple and everyday experience, but it made clear the highly specific relations that we have to smell, relative to all our other senses. It would be striking and eerie for us to see something in particular and for someone else not to even see it, or to hear a sound and for someone else not to hear (although we may conjecture that their hearing may be impaired), or to touch an object that another cannot feel. But smell is highly individualized, perhaps, like all the other senses affected by its experiences and memories, but also remarkably complicated – enhanced, or diminished – by its surroundings, by other smells and through the uncontainable, wafting nature of its object. Perhaps smell is the most personal and individualized of the senses? That some scents are discernible by some but not by others is systematic, and intellectually and biologically interesting. It is hard to see such a characteristic in any of the other bodily senses. And we know from Darwin, and from evolutionary theory more generally, the more upright homo sapiens became, historically, the less they came to rely on smell and the more they used vision to enhance their knowledge of their various environments, the closer we come to the evolution of the human species, in all its variations. We can be smelled (by other species, especially insects) more than we can smell (other species, other odors or scents). The idea of smell is an enhancement, or a warning signal or an alert, for the other senses to be brought into action. Smell warns us from afar what vision can address in detail.

I have a question about your experience smelling Frangipani with your colleague. Hormones influence the sense of smell. Can we identify the colleague’s gender?

What was fascinating about this encounter was I was with my oldest friend, a woman I have known since grade school, and neither of us could discern any smell in one of the two flowers. We experimented for several minutes: no smell from one flower and an intense smell from the other, but they were different flowers that unleashed access to an intense aroma for each of us, and for a while, neither of us could believe the other could not discern the intensely pleasant smell that the other experienced. For us both, this was a real surprise: we must have different olfactory receptors, different capacities for discernment of aromas.

I am not even sure these are linked to what we have previously experienced rather than to different nasal receptors. I have read that there are far fewer receptors in the nose (around 350) relative to, say, the eyes (which have thousands of receptors and large variations in color discernment, even color blindness), but that the nose is able to discern thousands of different aromas through the differential use of these receptors, perhaps even more variations than with vision. This is fascinating and something that has not been addressed in much detail, except in the rare work on the sense of smell such as the writings of Michael Marder, in conjunction with Luce Irigaray, and in his own writings.

Aromatic plants—whether through flowers, herbs, or trees—have long been associated with ritual, medicine, and aesthetics. Could you share your thoughts on how aromatic plants might relate to artistic expression? Do you see them as sources of inspiration or as part of the art-making process itself?

There is already an art of smell, although it is also a commerce (and the relation between art and commerce is always there in any of the arts, but smell has a specific and particular field that directs itself commercially), the world of perfumery, which has its own blenders, mixers, growers and chemists, and for whom a particular smell is an end in itself (and a very lucrative art). So, leaving aside the work of the perfume (and scent) industries at least for the moment, I have no doubt that scents and smells, especially aromatic plants, can be both an inspiration in the production of the other arts and in certain cases part of the art-making process. Painting, sculpture, film, music, literature, can both accommodate plants themselves into their different creative objects or techniques, using trees for instruments or objects of investigation, creating musical instruments from some of them, making paper with them, using scents while acting and so on.

In your work, you’ve emphasized the importance of the body in creating and experiencing art. How do you think our sensory experiences, particularly our sense of smell, play a role in artistic creativity and perception? Are there any connections between aromatic plants and bodily experiences in the production of art?

The most striking creative work that uses smell as a method is cooking. We often don’t think of it as an art (and often it does not look artful or even pleasurable to do!) but cooking is also a magical mode of transformation of plants (and animals), using aromatic spices, leaves, and so on to enable both the practical elements of calorie-intake but also, with luck, the creativity of the minor or everyday arts, enhanced and intensified in commercial cooking. Our sense of smell is also the ongoing accompaniment of all of the arts and indeed, all production. We are surrounded by smells and odors wherever we work, whether we pay attention or not.

Many cultures use aromatic plants in rituals or ceremonies, often involving specific olfactory experiences to alter states of consciousness. How do you see these sensory practices as connected to the creation of meaning, symbolism, and art? Can aromatic plants transcend their utilitarian uses to become part of an aesthetic or artistic language?

Yes, you are right that in many cultures, even elements of our own, using aromatic plants is central to some rituals and religious practices, even mainstream ones. I understand that particularly in various Indigenous (and non-indigenous) rituals and ceremonies, there is a contained or uncontained alteration of consciousness that, for some at least, can lead to symbolic, theological, and artistic insights and impulses and that for others may stimulate artistic aspirations and provide inspiration for literature and the other arts. You ask if aromatic plants can transcend their utilitarian uses: but as you have already shown, they must transcend usefulness already. The desire for these aromas and the plants (and chemicals) that may produce them abounds, and much of its appeal lies in attracting the interest of others, or in soothing oneself directly with something intangible but pleasurable.

In your work, you often explore themes of sexuality and desire. Aromatic plants are often associated with attraction and sensuality. How do you see the relationship between scent, sexuality, and art? Is there a way in which aromatic plants evoke a more primal, bodily response that challenges traditional artistic forms?

There is, as you suggest, a quite strong relation between scent and sexual attraction and behavior. In fact, I suspect that the clearest evidence of the place of scent for many humans is in the broad arena of sexual engagements, whether flirting (possible sex) or sex itself. We, or at least some of us, use perfumes and after-shave type aromas to feel as attractive as we can, to enhance our presence (and our confidence), in the encounters with others to whom we are attracted. Sexuality is the space in which scent is both at its most intensive and its most exciting. Or as you say, primal. I do not doubt that sexuality and artistic creation have a direct connection – it is the same intensity, energy, and sometimes, pleasure (or pain) that is experienced, but not usually as genital (this of course may depend on the particular type of art!) but mediated through the practices of artmaking involved. What is more difficult to assess or even theorize is the strength of the place that scent may have in how sexuality, sexual impulses, and energies, connect to and enable or make possible various artistic practices. I suspect that the more traditional the art form, the more indirect the connection between scent and artistic production (and I could be wrong here). Given the great variability in how and what people smell and find attractive or repulsive, I cannot see scent as more than one of the apparatuses of sexuality and pleasure (and safety) that we bring to bear on creative practices. In rare cases, in, for example, the creation of multi-art spaces and performance spaces, especially immersive art spaces where video, hanging paintings, movement, and lights function together, the possibilities of scent-focused or scent-enhanced art forms are more readily facilitated and less unexpected.

You have argued that art emerges from excess—the exuberant play of the body and mind. How might the excessiveness of fragrance or the rich, complex nature of aromatic plants contribute to artistic expression? Could you envision a specific form of art emerging directly from the engagement with smells, perfumes, or natural scents?

To answer the last question first: I can’t imagine a specific form of art (other than perfumery, or ‘smelling groups’ that might be the nasal equivalent of reading groups) that is its own specific form, without the interplay of architectural, lighting, seating and other artistic forms to supplement it. This is in part because of the dissipative nature of smells, which are not directly containable, even within most forms of material framing. Smells move with the air, which is both their strength and limit. I do think art emerges from excess, and specifically, sexual excess, the excesses induced by the struggle for attractiveness, and that fragrances are now enhancements to the (small) pleasures of smelling for its own sake. I think that aromatic plants may form part of the inspiration for the ongoing production of works of art, at least for some individuals, but not for all or perhaps even most. I must admit though that this is purely a speculative thought.

You’ve written about the materiality of the body and its interactions with the world. How might the materiality of aromatic plants (their oils, textures, and odors) intersect with the materiality of artistic practices, such as sculpture, painting, or performance? In your view, could scent become a material component in contemporary art-making?

It could. And in some cases, particularly in examples of art that use wood in the making of the art-work, this is necessarily so, even if it is a minor consideration or an unconscious component. A scent-component could become part of some contemporary art-making, especially if someone like you, opens our noses (rather than our eyes) to an awareness of its potential uses and the bodily effects they may generate! I don’t know how widespread this could become, and this is perhaps an effect of our ignorance of how smell and the use of scents function.

Aromatic plants have different significations across cultures—whether as symbols of healing, love, or spirituality. How can artists draw from these cultural meanings and incorporate the power of plants and their aromas into their creative processes? How might this contribute to the politics of art and cultural expression?

There are two different questions here that I think should be separated: there are different significances of and uses for aromatic plants across different cultures. They may be used in both cooking as well as what you call spiritual functions; and they may and have been used for healing and in the expression of love. But the degree to which these cultural practices can be appropriated by other cultures remains an ongoing question with its own problems. Using practices from other cultures must involve (but often in the real world does not) a deep awareness of the history and context in which these practices occur and the meanings they have for those who have for generations been involved in them. More often than not, in my awareness, this is not true: a practice – such as the use of ayahuasca and other plant-based psychedelics that are used in other cultures’ religious practices – is often a clear appropriation that lacks a local, non-financial understanding, cultural contexts, and historical awareness. To answer your first question: I can’t answer how artists may draw on the cultural meanings of plants and their aromas. Except to say again: there could and should be more attention given to the olfactory, in medical, theoretical and artistic terms, but until someone begins this process of conceptualization, as you have, the conversation cannot even begin.

In your work on sexual selection, you argue that art may be linked to mate attraction and reproductive signaling. How might aromatic plants fit into this theory? Could the scent or use of certain plants have evolved as part of artistic practices, serving a similar role in attracting attention, signaling creativity, or enhancing social cohesion?

Aromatic plants, too, exhibit a form of sexual selection by enticing precisely the insects and other fertilizers to enable these plants to reproduce in nature. They don’t attract their own species, as most forms of sexual selection tend to do; they attract those other species, usually insects, they require for pollination. They too have their own forms of sexual selection. Certainly, some plants that humans have cultivated have evolved (under the forces of external or specifically selected characteristics chosen for human pleasure) but like other cultivated species, both animal and plant, they evolve in directions not chosen by natural selection but through cultivation or ‘artificial selection’, as Darwin calls it. They signal the attraction and attention of human cultivators.

As someone deeply engaged with the concept of excess in art, do you see aromatic plants as part of this excess? Their overwhelming scents or their association with lush gardens and forests might reflect abundance or indulgence. How might the rich olfactory world of aromatic plants contribute to the notion of art as surplus or excess?

Yes, I do believe that aromatic plants are part of the excess over-survival that all forms of life exhibit. Certainly, these plants in their natural habitats elicit a natural attraction from those species attracted to their smell and the effects they elicit from the living beings sharing this habitat. As I suggested, I think that plants can contribute to the surplus of qualities and their transportability elsewhere, that is, to art, but not in themselves. In themselves, they are the center of their own universes, seeking survival and growth from their environments, flourishing or not according to external conditions that involve a milieu, other living beings, other plants, soil, weather, and so on. Art, in my opinion, involves the deterritorialization of qualities – their transportation and transformation in some way, even if it is the most minimal form of framing (such as a fence or enclosure). Art, as such, is always in whatever way deterritorialized, moved, framed, or transported, not through nature but through (arbitrary) artifice.

In many ways, aromatic plants are also bound up with ecological and environmental concerns, especially given their role in biodiversity and sustainability. From a feminist perspective, how might the practice of incorporating plants and their aromas into art challenge or subvert traditional hierarchical relationships with nature, gender, and the body?

The place of all plants is now clearly of significance in our understanding of the earth as a planet of widely different habitats, environments or Umwelten. Without plants, there could be no animal existence and animal species evolve in an environment that it occupied by forests, plains, mountains, and oceans that each produce the species that continue to reproduce, even given the environmental devastations wreaked by humans in spaces whose mineral or unliving deposits become of greater concern and action than the living beings who co-occupy planetary space. Art is one way to challenge prevailing social practices, in an indirect way (as are demonstrations or more directly interpretable forms of protest), but as we know, its (political) impact is mediated by its viewer’s actions, its political impacts – with rare exceptions – are internal to the history of art rather than to the fears of contemporary society. I am aware that there is currently an urgent production of artworks of various kinds (films, paintings, performances, music) which addresses climate change and crisis. All these expressions are part of a resistance, but a small order of resistance, in a bigger world of politics, war, and money. Art is what individuals and small collectives can undertake and produce to resist with style, with innovation, what resists the orders of production and consumption that regulate other commodities. The place of smell and aromas, along with the other arts, is small but significant.

The growing interest in “plant art” and eco-art shows how contemporary artists are looking to nature for inspiration, not just visually but also sensorially. How do you see this shift toward working with living systems, scents, and botanical materials in the context of art and the body? Is this a feminist or radical reclamation of art’s connection to the natural world?

I agree with you that there has been an increasing interest in plant art and eco-art. Artists have returned to nature with a renewed interest in both representing and preserving at least images of the natural world, even as various environments are ravaged by mining, tree felling, and land-clearing. The ecological protests at various distinguished art galleries across the world have, perhaps not very articulately, highlighted how art is implicated in the same ecological disasters that affect us all. (There have been at least 40 reported protests in the last few years that have had well-known paintings or installations, including The Mona Lisa, smeared with soup, oil, and other substances in protest against oil, or against the ‘art-washing’ of polluting companies, or companies that profit from human misery.) A reclamation of art’s connection to the natural world is a welcome thing, as long as its simultaneous connection to the world of value and finance is made clear and understood. Art is precariously balanced between nature, politics, and the worlds of people who produce and sell art and make its raw materials possible.

Having been born in Australia, with eucalyptus being a dominant smell in the air for a good part of the country, do you personally have any relation to the smell or when you sense it in the States, does it trigger any memories of home?

I wish that eucalyptus was a dominant smell in Australia, but like much of the US and globally, industrial and cooking smells seem to pervade city living. I have a eucalyptus tree leaning over my own place, its leaves fall into my garden from next door, but its aroma is not really discernible to me. I think that the leaves need to be crushed to open up their aromas. I believe that in the countryside it may be more noticeable with greater tree density, but personally, I have never really been aware of its scent except in commercial products.

I live in Manhattan in the US, so for me, the primary aromas are not very pleasant, mainly human and animal waste, trash and so on. There are times of the year, Spring primarily, where everything begins to bloom and the parks smell beautiful, at least when they are not covered with fertilizers. But natural smells seem to me quite rare outside of parks in the city.

Iconic aromatic treasures are disappearing from under our noses.

Gayil Nalls, PhD is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist. She is the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy and the editor of its journal, Plantings.

Plantings

Issue 45 – March 2025

Also in this issue:

Manchán Magan’s Memories of the Bog

By Gayil Nalls

Lucy Henehan, Co-founder of Iveragh Eco Forest

By Gayil Nalls

Plant Cells of Different Species Can Swap Organelles

By Viviane Callier

Przewalski’s Horses and the Ecological, Cultural, and Olfactory Significance of Dung

By Gayil Nalls

Climate change is making plants less nutritious − that could already be hurting animals that are grazers

By Ellen Welti

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Versatile Seed Crackers

By Octavia Overholse

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.