From Billion-Dollar Flows to Gooseberry Jam: Fraser Howie’s Voltairean Turn

By John Steele

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

There is a quietness to rural Scotland that has nothing to do with silence. It is the quiet of time stretching out—not rushing forward as in cities but expanding like the rings of a tree. On a mild September morning, Fraser Howie is gathering pears from a tree beside his house. It is the same tree that, when he first arrived, yielded nothing. The work is simple and absorbing. A few years ago, he was managing financial flows across Asia; now he is tending to soil and branches.

Howie’s transformation is not an act of withdrawal but of reorientation.

Voltaire closed Candide with the injunction: “Il faut cultiver notre jardin”—we must cultivate our garden. Howie has done exactly that.

Q: How did you end up leaving Asian finance and returning to rural Scotland?

Fraser Howie: “There was certainly no plan. I had been over 30 years in Asia. Had worked in Beijing, Hong Kong and Singapore and I often wondered where I’d end up. At some point I knew I’d stop working, and look to re-orientate my but life but I never quite knew where that would be. I just didn’t know.”

He explains that the turning point was the pandemic. “It was very much COVID that changed things. We were in Singapore, my daughter was in boarding school in the UK, my son was in middle school, and then COVID came along. Singapore was very restrictive. The school in early 2021 basically said, Look, there’s going to be no trips for the coming year and no trips for the year after. Because of the rules, my son could leave the country, but he couldn’t get back in. And I just thought, this is—you only get your early teen years once. We’d be so restricted if we stayed. So I asked if he wanted to go back to the UK to finish school, and everyone jumped at the idea, which surprised me. So we came back.”

Q: Was this shift philosophical for you?

Fraser Howie: “I think the answer is yes, but the full answer, or explanation, is still forming in my own mind.”

He recalls one conversation that lodged in his head. “One of my friends had said to me, what’s this rush to get back to normal? Was normal, really so good? And that made me think about things and about the pressure of work. I was on a plane once a week and sort of enjoyed what I did. But at the same time, it was just…that was what I did. I never really thought much about it.”

Q: Had you ever gardened before this?

Fraser Howie: “Nope. Never.”

When he bought the house, it came with fruit trees, berry bushes, and overgrown beds. “I eat a lot of fruit and, of course, as I said, when I bought this place, there were a lot of existing fruit trees and berry bushes which I wanted to develop. But that was a bit of a prod to me to say, look, I’m in this microclimate here on the Cromarty Firth, and look how good the soil is, and look how many things can grow.

In the Scottish Highlands, which most people would think of as being sort of bleak, cold, and rainy all the time, yet… I have a very, very productive garden. When I bought the house, there was no fruit on that big pear tree because it hadn’t been tended well. There was a big rose bush growing through it. We (my gardener and I) cut that back, we gave it some fertilizer, kept the weeds at bay, and let nature do the rest.. This morning, I probably took a thousand pears off it. I am really enjoying this.. I like the long-term project aspect of it.”

Q: Does any of your financial mindset carry over into the garden?

Fraser Howie: “One of the guys I worked with used to say about our projects, “we understand it can be slow, but as long as the gradient’s positive, we’re happy”. And that’s how I see this. Day by day, week by week, season by season—if it’s moving in the right direction, then we’re doing well. “

He also sees gardening as a system, much like markets. “I always saw our finance business like a chain with the links composed of the compliance, IT, legal, finance et cetera, If any of those links broke or someone didn’t agree, ultimately the business didn’t get done. In the same way that’s true in the garden. I’m interested in every aspect of developing the garden and land. I can’t just turn a blind eye to it or say I don’t like doing that bit. I would like to do less weeding, but you need to get rid of the weeds if you want the tree and bushes to prosper.”

Q: How do you think of your role as a gardener now?

Fraser Howie: “I still don’t really think of myself as a gardener. I see myself more as a steward. The main house was built in 1738 as the manse of the local church, and a number of the ministers over the centuries were known to be passionate about the garden. While we’ve done some new things, I see myself in that long tradition, and much of the work is about bringing what I inherited back to better condition.”

Q: Tell me about the microclimate there.

Fraser Howie: “There are these little pockets in Scotland of microclimates. It’s interesting when you look at the weather forecast on the TV for Scotland, there the Highlands gets one weather symbol, and yet it’s a very different experience between the east coast and the west coast. The west coast is generally much wetter, much more rain that’s being much more exposed to the Gulf Stream coming up from the Gulf. Whereas on the east coast we’re much more protected.”

He explains that two formations, the Sutors of Cromarty, shelter the Cromarty Firth. “The firth is very deep and it’s quite protected here. The mountains protect us from some winds, and we enjoy less rain and more sunshine than in many parts of Scotland.”

Q: When you see your old finance colleagues, how do they react to this new life?

Fraser Howie: “They do look at me in a bit of disbelief that I’ve moved—from billion-dollar flows to weeding my garden and making jam out of my gooseberries. They can’t quite believe it’s me. And yet I think, no, it’s just me. This is just a different project.”

Q: You’ve said both markets and gardens face shocks. What have you learned about resilience here?

Fraser Howie: “Literally one of the first things I did was get a tree surgeon to come and review the trees. I didn’t want to wake up one morning and find a tree through my roof or on my car. Disaster strikes, markets crash. So, I was hedging myself—I got the work done before anything came down. And thankfully, while some branches have come off, in three years I’ve never had a tree down, and there have been some nasty storms.”

Q: What’s it like moving from a global financial community to a Highland village?

Fraser Howie: “It’s only when you get to places like here that you discover how abnormal my life was before—the amount of flying I did, the fact that in cities you just go out all the time and you are on call pretty much 24/7. All that pressure, but it’s just what the job is, but since everyone is doing it you don’t think it strange. Moving here, you realize life doesn’t need to be run like that.”

He has found the Highlands full of independent and entrepreneurial people. “It’s a different environment, but there are a host of interesting people.”

Q: You’re turning this garden into something more. What are your plans?

Fraser Howie: “I do actually want to make this into something of a viable business of sorts. Obviously, I’m not going to be challenging the Central Valley for fruit production, but we’re certainly looking at farm shop-type things, making products, maybe hosting some events. I’ve got good ground here. It just takes time to get to that stage.”

Q: You were trained as a scientist. Does that come into play here?

Fraser Howie: “I would certainly suggest that for anybody who’s going in that direction to study botany or something like that, get them to weed a garden for a few weeks, and they’ll suddenly discover the reality of plant life.”

Fraser Howie still keeps a flat in Singapore, travels occasionally, and is learning Japanese (he learnt Chinese in the late ’90s). But the center of gravity has shifted. “I think pretty much from April through to September, I’m never going to leave here,” he says. “There is just too much to do.”

Voltaire’s line was not, finally, about resignation. It was about choosing to invest in what one can tend with care. In the shade of a pear tree, with soil under his fingernails and plans for a new harvest, Howie is living that choice.

John Steele is the publisher and editorial director of Nautilus Magazine.

Plantings

Issue 53 – November 2025

Also in this issue:

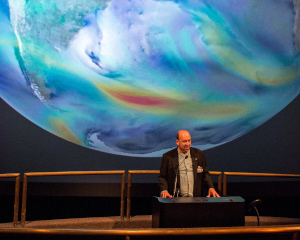

Time, Layers, and Climate Futures: A Conversation with Dr. Gavin A. Schmidt

By Gayil Nalls

Nature’s Prescription for Our Future

By Dona Bertarelli

Scale Sensing: The Dance Between Geologic and Biological Time

By Willow Gatewood

Kneeling Down to Look Again – a Way Back to Earth

By Margherita Gandolfi

Manchán Magan’s Memories of the Bog

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Roasted Portobello Mushroom

By Gemma Monici

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.