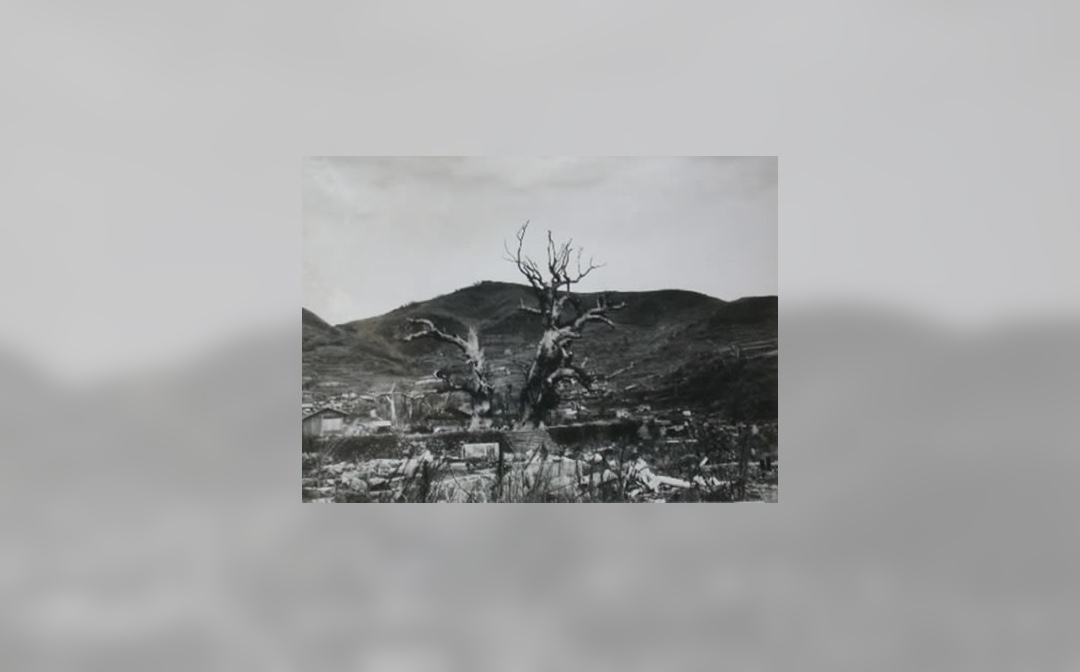

Sanno Shrine, Nagasaki: Surviving camphor trees in naked silhouette, 1945. The trees were 500 years old at the time of the blast. Today these trees have new branches and leaves and continue to survive.

Life Always Wins. Follow Me

A botanist is introduced to escapees from the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

By Stefano Mancuso

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Japanese cuisine is so varied and refined that it’s hard to happen upon something unpleasant to the palate. My personal procedure in Japan is to take a seat at the counter and start pointing, completely at random, to a series of dishes chosen on the basis of how much I like the characters with which they are represented. Normally, they turn out to be small dishes, with small servings, that in no time start crowding the counter space allotted to me, turning it into a little work of art. That’s the moment I like best: You feel the rush that comes with gambling, but without the risk, except the negligible one of a truly unsavory dish. Then comes the pleasure of discovery: What am I eating? What are the ingredients? How was it prepared?

During one of these blind dinners in Kitakyushu, I happened onto a mysterious dish that defied all my efforts to figure it out. It was a sort of whitish little pouch about the size of a ravioli, lightly fried and filled with a creamy substance tasting of fish. The flavor was delicious and so, having finished the first serving, I promptly ordered a second, so as to study it in depth. It reminded me of something from Italian cooking but I couldn’t put my finger on it. I puzzled over it for a while but nothing came of it. I even tried to talk to the waiter about it, but in Japan hardly anyone speaks anything but Japanese. Disconsolate, I was ready to ingest the second serving, leaving my queries unanswered, when something totally unexpected happened—one of those things that make me love going out to eat by myself in Japan.

The consul was struck by my knowledge gap. “But you are concerned with plants! You simply must meet them.”

An elderly man, sitting next to me at the counter, addressed me. That in itself is crazy. Never in all my years of visiting the Land of the Rising Sun had anyone spoken to me without being spoken to first. I had always been the one to start a dialogue. But that’s not all: He spoke to me in perfect, elegant Italian that hit a bump just for a second, right at the start of our conversation, when, embarrassed, he couldn’t find the right words to tell me, without scaring me, what I was eating.

“You see, dear sir, we give great importance to the reproduction of life,” he began, leaving me a bit disoriented. “Even though our culture is often noted in the West for its aggressive connotations, in reality there is a strong component of panpsychism [that’s the word he used] in our civilization.”

I reassured him, for reasons of courtesy, that this aggressive connotation of Japan belonged more to the past than to the present. The look on my face, however, must have remained puzzled. What did panpsychism have to do with what I was eating? He tried again.

“As a consequence of the presence of the divinity in everything, we tend by tradition to consume every single part of animals.”

Now we seemed to be getting closer. And so?

“So, that dish that you are consuming, which by the way is called shirako and is without a doubt among my favorites, too, is produced from the male germinal line of various marine species.”

“The male germinal line? You mean …”

“Yes, what do you call it in Italian?”

“Sperm.”

“Exactly.”

So that’s what it reminded me of: milt, an exquisite Sicilian specialty with the sperm sacs of tuna or ricciola (greater amberjack), the male equivalent of bottarga or roe. The fact that in Italy people eat the same not-so-noble parts of fish (I believe for reasons much more material than those associated with panpsychism) reassured my new dinner companion.

We introduced ourselves; he was a retired diplomat. During his career, he had served his country as consul in Italy for many years, and he had learned the language. We went on to talk for a long time and with great pleasure until, just before saying goodbye, he asked me, “I imagine, Professor, that you have already had occasion to visit our Hibakujumoku,” and left the question floating in the air between us for a few seconds. I answered that I had never heard of them and that I was sorry about that. Whatever the Hibakujumoku might have been, it is not polite in Japan to say you don’t know about something without excusing yourself. The consul was very struck by this knowledge gap of mine.

“But you are concerned with plants! You simply must meet them.”

He said exactly that, “meet them,” so I thought he was referring to a group of people who in some way were concerned with plants. But his next words shattered my supposition.

“The Hibakujumoku are our escapees from the atomic bomb. A living hymn to the force of life.”

I knew that in Japan survivors of the bomb attacks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki held a fundamental position as witnesses to those atrocities. But I couldn’t understand the reason he was so insistent that I should meet them. The mystery did not last long.

“They are not people, but trees exposed to the atomic bomb. In Japan, everyone knows them and respects them. Personally, I love them. You should know them, too. I am going to allow myself to make a proposal. Hiroshima is not more than two hours from here by train. If you like, I can accompany you there in the next few days to meet them. Please tell me if you would like to do that. Since my wife died, my days are mostly free of commitments.”

I thanked him intensely and accepted his offer with pleasure.

Two days later, each of us armed with his own bento, as befits two friends on an outing, we met early in the morning in front of the train station in Kokura, ready for our trip to Hiroshima. In a little over an hour and a half, we arrived at the station in Hiroshima, and 10 minutes later we were standing before my first Hibakujumoku.

The consul had led me through a magnificent garden—whose name I unfortunately don’t remember—to “meet” three trees that had survived the bomb. I remember them very well: a ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), a Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii), and a muku (Aphananthe aspera), three very common trees in any classical Japanese garden. The ginkgo was conspicuously bent in the direction of the city center, the black pine had a considerable scar on its trunk, but all in all, they were in good shape. Normal trees by all appearances, if it hadn’t been for the evident feeling of respect and, I would say, affection that they inspired in the people who were there to “meet them.”

A genteel elderly couple (probably husband and wife) had taken a seat on two portable chairs in front of the ginkgo and were engaged in a long conversation with the tree. A young boy gave it a quick hug before continuing on his walk. Everyone who passed by the trees seemed to know them well, and many people, from kids to old folk, bowed deeply before them. On each Hibakujumoku hung a yellow sign, the only characteristic that distinguished them from the other trees. I asked the consul what it said.

“I’ll try to translate it for you. It says more or less that we are standing before a tree that suffered an atomic bomb attack. Then it gives the vegetable species and finally the distance from ground zero,” he explained, pointing toward the river. “The explosion happened down there, where the river forks, exactly 4,494 feet from here.”

He looked me straight in the eye and said, “Talk about the Hibakujumoku, make them known.”

That day I visited a lot of Hibakujumoku, making my way closer and closer to the place where, for the first time, an atomic ordnance was used against a defenseless population. I remember another magnificent ginkgo inside the enclosure of the Hosenbo Temple at 3,700 feet. A camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora) inside the quadrilateral of the Hiroshima Castle, at 3,674 feet. A Kurogane holly tree (Ilex rotunda) also inside the castle grounds at 2,985 feet. A marvelous peony (Paeonia suffruticosa) in the temple of Honkyoji at 2,920 feet.

As we moved in closer to the center of the disaster, the Hibakujumoku began to thin out. At 8:15 in the morning on Aug. 6, 1945, the ground temperature in the place where we now were had risen above 7,200 degrees Fahrenheit; very probably it went as high as 10,800 degrees Fahrenheit. The consul had just taken me to see the shadow (literally) impressed on the stairway of the Sumitomo Banking Corporation, left by the vaporization of Mrs. Mitsuno Ochi, age 42 at the time, caught unawares by the explosion as she was waiting for the bank to open. No hope that anything could have survived all that destruction. I voiced this thought to the consul, who responded, smiling, “Man of little faith. Life always wins! Follow me.”

We went around the corner and found ourselves once again along the Honkawa River. The “atomic bomb dome,” the only building left standing and preserved as a peace museum, which by convention marks ground zero, was there in front of me, at less than 1,300 feet from where we were, and there, too, right in front of us on the riverbank stood the champion of the Hibakujumoku, a weeping willow (Salix babilonica) reborn from its roots left alive underground. Its yellow sign indicated a distance of 1,214 feet from ground zero.

On the way back home to Kitakyushu that evening, the consul invited me to dinner at an inn he knew. I gladly accepted. It was a very pleasant evening and we drank a lot, as often happens among friends in Japan. As we spoke about our “encounters” in Hiroshima, something left me puzzled. Each time the consul spoke of the Hibakujumoku, he defined them as “trees that had suffered an atomic explosion,” and this long circumlocution sounded funny and strangely discordant with his otherwise perfect proficiency in Italian.

So I dared to venture, “Excuse me, consul, why do you keep saying that the Hibakujumoku are “trees that have suffered an atomic explosion”? Wouldn’t it be simpler to use a word like “survivors”?

Here is his explanation: “The question is more complicated than it seems, dear Professor. It all starts with the name given to the survivors, as you say, of the bomb. Their name in Japanese is hibakusha, literally ‘person exposed to the bomb.’ There is a reason for this choice that you can grasp. This term was chosen rather than ‘survivors’ because that word, by exalting those who had remained alive, would have inevitably offended the many who died in the tragedy. As a consequence, the Hibakujumoku are referred to in the same way. I imagine that seems strange to you, but I assure you that all hibakusha are content about this and could not have abided being called ‘survivors.’”

I suggested the Italian word reduci, or “veterans.” He didn’t know it and he liked it very much. “Thank you so much for teaching me that word. It sounds very good. Let’s toast to our veteran friends.”

“I have to tell you. I, too, am a hibakusha. I was seven years old when the bomb did away with my whole family and everyone else in the world I knew. I was saved because the classroom in the elementary school where I was studying was protected by a curtain of trees.”

After leaving the restaurant, I insisted on accompanying him home. No one would have guessed it from looking at him, but the consul was well over 80 years old, and he had had a lot to drink. In any event, he agreed, and I accompanied him on the short walk to his home. We said goodbye. Breaking every Japanese rule, by virtue of his many years spent in Italy, the consul hugged me. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “Talk about the Hibakujumoku, make them known. And come back to visit them again.”

He paused, trying to decide. “I have to tell you. I, too, am a hibakusha. I was seven years old when the bomb did away with my whole family and everyone else in the world I knew. I was saved because the classroom in the elementary school where I was studying was protected by a curtain of trees. I and four of my classmates are the only veterans from that school. We were 120 children.”

He thought about that for a second, smiled at me one last time, and, turning to pass through the door to his home, thanked me again for my company.

Stefano Mancuso is one of the world’s leading authorities in the field of plant neurobiology, which explores signaling and communication at all levels of biological organization. He is a professor at the University of Florence and has published more than 250 scientific papers in international journals. His previous books include The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior and Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence. Translated by Gregory Conti.

Excerpted from The Incredible Journey of Plants by Stefano Mancuso, translated by Gregory Conti. Published by Other Press. First printed in Nautilus magazine.

Photo: Photographed by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, 1945; Committee for Research of Photographs and Materials of the Atomic Bombing, Nagasaki Foundation for Promotion of Peace — Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.