Plants, Psychodiversity, & the Paranormal: in Conversation with Dr. Jack Hunter

By Jake Eshelman

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

W hen people talk about plants, it’s usually in terms of their utility for us—how they look, smell, taste, or grow for our benefit. But plants do much more than we give them credit for. At very least, they nourish, deplete, heal, poison, maim, salve, trick, and collaborate. And by virtue of these myriad behaviors, plants are incredible teachers. They embody principles of cooperation and competition. They model clever strategies to adapt to changing environments. They illuminate the ecological importance of reciprocity. In other words, they show us how to be in community.

These are the conversations about plants I enjoy being a part of. In that light, I’m thrilled to share such a discussion with Dr. Jack Hunter, an anthropologist who has done phenomenal work exploring the borderlands between consciousness, religion, ecology and the paranormal. As you’ll see from our conversation below, thinking deeply about plants presents us with ongoing opportunities to reimagine ourselves, our behaviors, and the world(s) around us.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity

I first discovered your work through the anthology you edited, Greening the Paranormal, and I feel that would be a fitting place to start. Perhaps you could share a bit about your interest in the relationship between ecology and what we might call ‘paranormal’? How do those two things intermingle for you?

Well it might seem like they are two vastly different domains. On the one hand, there’s ecology, which comes out of the academy and generally refers to the science of relationships between organisms and their environment. And then there’s the paranormal, which is supposed to be this irrational domain of thought and experience. There’s of course a tension here, because the dominant scientific models underpinning mainstream ecology maintain that the paranormal can’t exist—that there’s no such thing as spirits or ghosts or anything like that. So it seems like they’re two fields that wouldn’t really come into contact with each other, but I think there’s a number of different ways that they do.

Towards the end of my PhD, I started working on a permaculture project in our local area. I got introduced to all of these ideas about natural systems, Gaia hypothesis, and so on. But what I really took away was the realization that if we really want to understand the world, we need to think about it in terms of complexity. We can’t reduce it down to any single discipline—psychology, pathology, chemistry, social functions, or the like. None of these alone are enough. We need them all, working together. So I started to see that complexity seems to be a principle that underpins everything including ecology, which itself implies a dynamic network of relationships and interdependence.

It’s interesting because academically speaking, ecology is a relatively new science—at least in terms of how it’s been codified. And yet the ideas that we’re exploring here aren’t new at all. People have had what we would call ‘anomalous’ experiences and encounters with plants for as far back as we can reach.

Exactly. Broadly speaking, people tend to assume that the scientific expression of ecology is the only one that’s relevant. But we also have Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) systems all over the world. And these worldviews tend to include the spiritual or non-physical side of things, such that plants and trees have spirits and personhood baked into a scientific understanding of how local ecosystems work. So ecology doesn’t necessarily have to be averse to the idea of a dynamic, living world. The scientific and spiritual can overlap with each other.

In my own research and conversations about similar ideas regarding plants, there are these moments that crop up again and again where people have shared their experiences of receiving insight, knowledge, or communications directly from plants. But it’s been relatively easy in academia to write this off as superstition. And then, some new lab-based scientific study corroborates what people have been experiencing—for example, confirming that plants respond intelligently to changes in their environment, that they can learn and remember, that they’re social beings, and that they even display signs of ‘swarm intelligence’. And it seems that people get really excited about these studies, which in a way only confirm what many people have already known, sometimes for thousands of years. And I think it’s interesting to consider why we tend to privilege academic knowledge about plants over people’s direct experiences in relationship with plants.

Absolutely. I think it shows how reductionist scientific thinking can be. If you look at most plant research, you’ll find a discrete study exploring plants’ capacity for memory, and then you’ve got a separate study about how plants sense their environment, and so on. But when we’re able to join all of it together, including other knowledge systems like TEK, the larger picture suggests that plants have all these simultaneous capacities to perceive and interact with the world in much the same way we do. All of this points in the direction of recognizing the subjectivity of other beings.

But for me this runs deeper than a mechanistic explanation of plant behavior. I’m thinking about how sunflowers will follow the sun across the sky. Some might say that’s just a mechanism at work in the plant and that it doesn’t require or suggest the presence of a sunflower intelligence. But I personally think it’s irresponsible, if not outright naïve, to categorically dismiss a plant’s capacity for agency and intelligence.

That’s where animistic traditions are essential, because they tend to take the holistic view to see a plant as more than a cluster of capacities, but rather as a complete person. So you have to engage with it as a person—a being—rather than a mere ‘thing.’

So if more people understood plants in this way—as individual beings with their own distinct ambitions, personalities, and intelligence—what do you think the implications would be following that shift in perspective?

They would be profound because we would have to appreciate that the world runs on subjectivity. I’ll add that we’ve been talking about plants as individual beings, but they might not perceive themselves that way. Plants live in groups, colonies, rhizomes, and so on. You can have many different plants on the surface that are actually connected underground as one large being. So we need to expand our imagination to consider different kinds of minds that might be out there. Plants might not be individual minds in the same way that we perceive ourselves to be individuals. They might be constantly experiencing the connection that we only sometimes experience in telepathic moments.

I remember reading something about how we tend to think of plants as stationery because they literally root into a place. But if you look at plants from a species perspective and think about how they reproduce, you then start to see how mobile they are. Partly because they collaborate with others—birds, bees, wind, and so on—to travel and roam across the Earth.

Right. And we can trace their movements with climate change. When certain areas become warm or cool, the plants flee or colonize. And again, it’s on different kinds of scales—even time scales. There’s a forest not far from where I live. We call it the “Bouncy Woods” because you can sit and bounce on the sprawling limbs of the oak trees that grow there. I’ve been going to that forest for 30 odd years, and over that time I’ve seen how the acorns have gradually spread outward, creating all these trees that used to be saplings when I was young. It’s been interesting to see that forest move over these long timescales that we sometimes don’t recognize.

It’s interesting to think about the language we use to describe how forests move. Even just now, we talked about how plants ‘colonize’ new areas. But we don’t often talk about forests as ‘migrating’—and I think that’s an interesting possibility. Like Ents!

Like Ents!

Exactly! They’re actually an ideal segway into one of the things we’ve talked around but haven’t specifically touched on yet. So I wonder if you might talk about the value of psychodiversity, especially when it comes to our relationships with plants.

I tend to use the term ‘psychodiversity’ as a parallel or complement to the concept of biodiversity. We really emphasize the biodiversity of places, but in doing so we tend to reduce everything down to the ‘bio’. But scientific research and animistic traditions both point towards trees as being much more animate and sentient than we give them credit for. So there’s this other aspect to consider about plants beyond biodiversity itself. After all, when we lose biodiversity, it’s not just biological stuff that we’re losing. It’s also other-than-human cultures, ideas, and worldviews other species have created to adapt to their local environments.

When you look at ecological systems developing over time, they move towards increased diversity. So you might start off with a blank, barren planet. And eventually life forms emerge that enrich the environment, making it viable for other organisms. And that increased complexity continues until you get rainforests and such. I think the same process also underscores consciousness as well. We can also imagine minds that have evolved or adapted to or embedded into other kinds of niches, like within rocks or rivers. So all in all, psychodiversity suggests that we might see minds in many different places—much more than just within the biological realm. Ultimately, psychodiversity is an opportunity to pay better attention to the sentient capacities of the world.

It strikes me as an invitation to nurture deeper relationships. For example, it’s one thing to use plants—to grow them or eat them or pulverize them for medicine and so on. It’s another thing to think about plants. And another thing entirely to think with plants, say through meditation or even psychedelic conversation. From your perspective, why is it important to engage with plants on these different levels?

We have led to this current ecological crisis that threatens all kinds of different life across our planet. And we need to look to other ways of thinking about the world in order to rectify it. The dominant models we’ve been using have led us down this path. And I think part of that process of evolving includes looking to different human cultures, but especially other-than-human cultures. We have a lot to learn from the ways plants do what they do and the systems they’ve set up to help other species flourish.

I’m curious: in your research and experience, is there anything you’ve learned directly from plants? What have they taught you?

In different ways, yes. There have been times that I’ve consumed certain types of plants and have had things to revealed to me. But I personally don’t have experiences of plants talking to me. Or that I hear a voice or have any kind of explicit communication. But there are other, more subtle types of communications and learnings that take place through observing plants and tending gardens. For the most part, those are the kinds of teachings that I get. And they’re things like patience and priorities and how to work with different time scales. Plants also help me think deeply about the purpose of what we do. For example, there’s ongoing debate on whether plants intend to be altruistic. I think they might do. But regardless of intention, they nonetheless lay the groundwork for other species to emerge and continue that cycle towards greater diversity of life, mind, and so on. If we emulated plants in that way—if our culture was geared towards leaving the planet more fertile and diverse instead of increasingly depleted—that would go a very long way.

I think that’s about as good as any way to punctuate our conversation. So looking ahead, what is the best way for people to find and support your work?

You can find me online quite easily on my website. It’s a bit old fashioned, but it has everything you need on it; lists of things and such. But I’m also on Facebook and Instagram, so people are of course welcome to follow me there as well. And my books are available from most good booksellers, so if you make some enquiries you can get them in real shops, or you can find them online.

***

About the Author

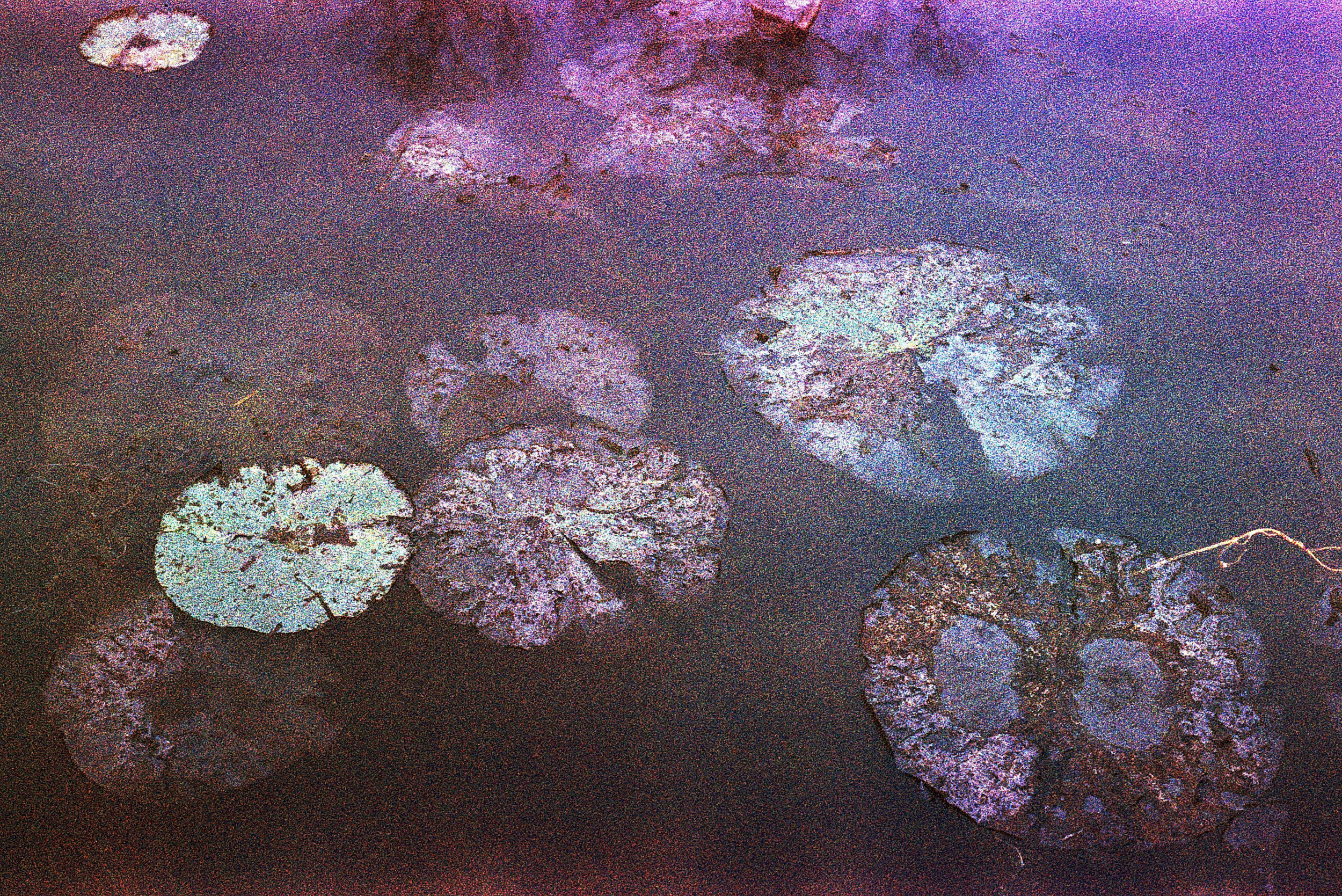

Beyond his role as the Contributing Editor of Ecological Thinking at Plantings, Jake Eshelman is a photo-based artist and visual researcher exploring the complex relationships between humans, the environment, and everyone we share it with. You can learn more about his work, writings, lectures, and publications online and via Instagram.

Plantings

Issue 39 – September 2024

Also in this issue:

The Art of the Brew: Exploring Hops and Other Plant Ingredients That Define Beer

By Gayil Nalls

Beyond the Brew: The Medicinal Power of Hops

By Ian Sleat

Beer Domesticated Man

By Gloria Dawson

Viriditas: Musings on Magical Plants

By Margaux Crump

Inside the Floral Mind: A Conversation with Kreetta Järvenpää

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Raspberry Balsamic Dressing

By Diane Reiss

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.