Institute of Plant Industry in Saint Petersburg, 13, St Isaac’s Square. Alex ‘Florstein’ Fedorov, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Seeds of War

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

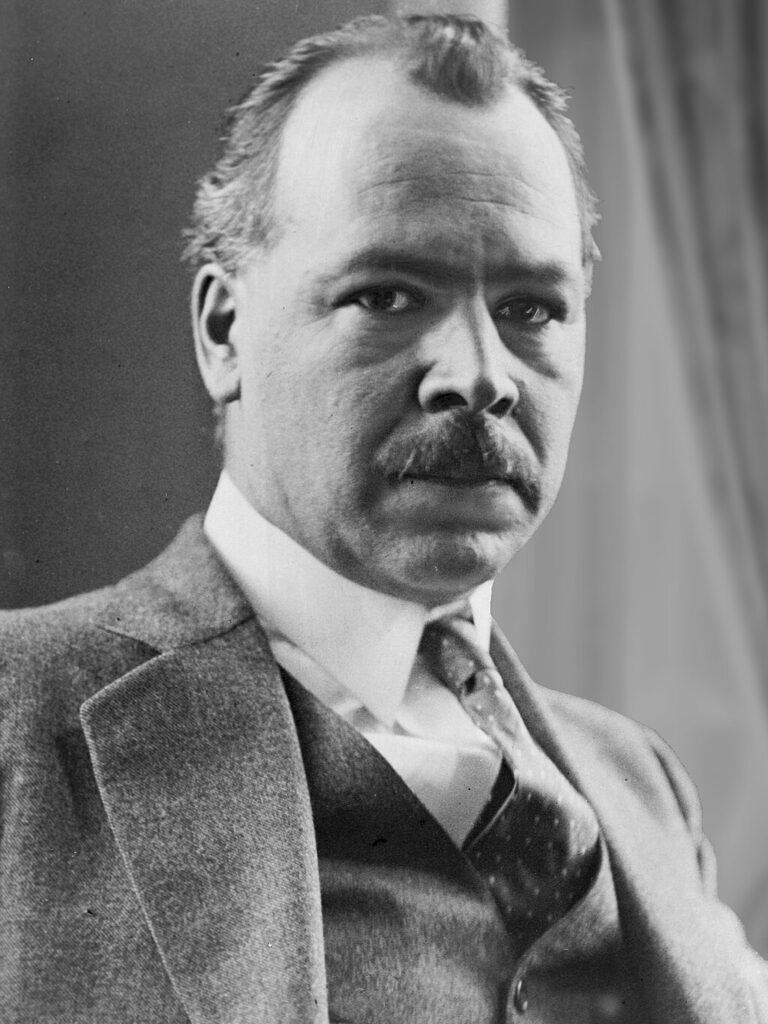

In the early 20th century, Russian botanist and geneticist Nikolai Vavilov had a simple but radical idea: if humanity wanted to end famine, it needed a library of life, a collection of the world’s seeds preserved for future generations. His dream was to amass a world seed bank scaled as a repository of crops that could feed the planet. In 1921, he founded what became the Institute of Plant Industry in Petrograd (later Leningrad, now St. Petersburg), the world’s first large-scale seed bank, with the explicit goal of gathering, studying, and safeguarding crop diversity from every corner of the globe.

Over the next decades, Vavilov and his colleagues traveled across continents, collecting seeds of wheat, rye, potatoes, fruits, nuts, and countless other crops. By the early 1930s, the Leningrad institute housed one of the largest and most diverse seed collections on Earth—well over 100,000 distinct samples, aimed at using this genetic diversity to breed crops resistant to disease, drought, and other threats.

Vavilov understood something that is now central to conservation biology: seeds and genetic diversity within crops are not a luxury, but a form of planetary insurance. Different varieties of the same plant carry different resistances, from rust fungi in wheat to late blight in potatoes, to heat and drought in cereals. Lose those varieties, and you lose options for adapting agriculture to new diseases, new climates, and new social needs.

Yet he was imprisoned and died there, and the seed bank he built was almost destroyed by war and starvation.

In 1941, during World War II, Nazi forces encircled the Russian city of Leningrad, beginning a siege that would last 872 days. Food supplies were cut off; hundreds of thousands of civilians died of hunger and cold. Amid this catastrophe stood the Institute of Plant Industry, by then holding hundreds of thousands of samples of seeds, tubers, and fruits.

Inside the institute’s converted palace and at its Pavlovsk Experimental Station outside the city, the remaining scientists faced an extraordinary paradox. On one hand, they were surrounded by rice, wheat, nuts, potatoes, and other foods that could have saved their lives. On the other hand, these collections represented the fragile genetic diversity that future generations might need to avert famine on a global scale. Many of the seeds were edible, but all of them were irreplaceable.

They took matters into their own hands. As later reconstructed by historians and science writers, including Simon Parkin in The Forbidden Garden: The Botanists of Besieged Leningrad and Their Impossible Choice, the institute’s staff made a collective decision: they would protect the seed collection at all costs, even from themselves.

They boxed up the most vital seed samples and moved them to safer rooms and basements to shield them from bombing, freezing temperatures, rodents, and their own hunger. They set up shifts to guard the rooms day and night. During the worst winters of the siege, rations in the city fell to starvation levels, and yet the scientists refused to eat from the sacks of grain and potatoes piled around them.

At least nine, and likely more than a dozen, botanists and staff died of starvation in those rooms, surrounded by food they had sworn not to touch.

Their sacrifice only makes sense if we understand what those seeds actually were.

Each packet of grain or bag of tubers represented a unique combination of genes: resistance to a particular rust fungus in one wheat line, tolerance to salty soils in another; early ripening in a barley variety from one region, drought resilience in a sorghum from another. Vavilov had spent his career mapping “centers of origin” for crops, identifying where wild and traditional varieties were most diverse so he could collect them before industrial agriculture and political upheaval wiped them out.

In other words, the Leningrad collection was a blueprint for future agriculture. From this living archive, breeders could one day draw on traits to face crises that had not yet arrived: new crop diseases, changing rainfall patterns, shifting temperatures under climate change. Modern seed banks, from the Vavilov Institute today to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the Arctic, are built on this same logic: store as much diversity as possible now, because you cannot breed or resurrect varieties that have already disappeared.

Parkin’s account emphasizes how clearly the institute’s staff understood this. Even in the middle of the siege, they saw their work not as abstract science but as a direct contribution to humanity’s survival. Their seed collection was forbidden because it was too important to consume. It sheltered 120 tons of edible seeds, but they ate nothing, determined to protect the world against global famine even at the cost of their lives.

The story doesn’t end with the lifting of the siege. The Pavlovsk Experimental Station, an outpost of the Leningrad Institute founded in 1926, became one of the world’s most important field genebanks, especially for fruits and berries. It holds thousands of varieties of strawberries, raspberries, cherries, and other perennials, most of which are maintained as living plants rather than seeds, and many of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

In 2010, this collection faced a new kind of threat: plans to convert the land into luxury housing. Because many of the varieties at Pavlovsk cannot be easily moved or stored as seed, the proposed development risked wiping out globally unique genetic resources in a single construction project. After an international outcry, Russia’s president intervened to halt the development, underscoring once again that the protection of plant genetic diversity is a political as well as a scientific responsibility.

Today, the Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry, renamed in Vavilov’s honor and still based in St. Petersburg, remains one of the oldest and largest seed banks in the world. Its vast holdings, along with those of other genebanks globally, are central to breeding climate-resilient crops, drawing on diverse landraces and wild relatives to introduce traits such as heat, drought, and flood tolerance. These collections not only safeguard future food security, especially for regions already grappling with crop failures and shifting growing seasons, but also preserve cultural heritage, as traditional varieties are deeply tied to local cuisines, farming practices, and community identities. The story Simon Parkin tells of scientists in besieged Leningrad guarding seeds even as they starved puts a human face on an abstract concept: biodiversity as a common good. Their choice makes sense only if we accept that the genetic diversity locked inside those seeds is worth more than any single harvest, any single lifetime.

The institute’s seed collection is the only one in the Russian Federation and is one of the top five leading gene banks in the world. Its wheat collection is one of the five leading in the world in terms of genetic diversity, along with Mexico, the USA, Italy, and Australia.

In that sense, the Leningrad seed bank is not just a story about World War II. It’s a story about how we value the future. Every time we protect a seed collection, save a traditional crop variety, or support a genebank, we are continuing the work that began in Vavilov’s institute over a century ago—and honoring the people who chose to die so that those seeds, and the biodiversity they carry, could live.

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D. is an interdisciplinary artist, sensory studies scholar, and the creator of World Sensorium. She is the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy and the journal Plantings.

Sources

Institute of Plant Industry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institute_of_Plant_Industry

Science History Institute: https://www.sciencehistory.org/

The Forbidden Garden: The Botanists of Besieged Leningrad and Their Impossible Choice, by Simon Parkin, Scribner

The inspiring scientists who saved the world’s first seed bank, The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/nov/12/food-source-famine-leningrad-seed-bank-nikolai-vavilov

Plantings

Issue 55 – January 2026

Also in this issue:

KEW’s Millennium Seed Bank: A Mission to Save Plant Life on Planet Earth

By Gayil Nalls

The Vampire Paradox

By Lewis H. Ziska

Creating Your Own Seed Bank

By WS/C

Learning the Language of Seed

By Liz Macklin

Seed Dreaming

By Willow Gatewood

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Rhus Juice: an Indigenous-inspired drink from the plant that connects continents

By Willow Gatewood

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.