Smound: how entanglement of scent and sound shape our world

By Willow Gatewood

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

My first memory of smell didn’t come until the autumn after my thirteenth birthday, and the experience, down to the timbre of Enya’s voice on the radio to the soft lap of wind on my face, remains one I can recall so vividly it’s as if I’m back on the bridge over the Cape Fear Sound. We had just rolled the windows down. Beach breeze and seagull cries filled my head. I inhaled to taste salt air, but for the first time, the chemical tingled more than the roof of my mouth. I gagged, shocked by the twang that overwhelmed my nose.

Likely caused by chronic sinus infections as a baby, the closest acquaintance I’d had to scent until then was taste. Sometimes, I’d inhale something deep enough — spice, or moist forest air — enough to taste it. But smell opened up a new world to my young mind, one that bloomed in startling and beautiful ways. There was, and is still, no “bad” smell. Since discovering the magic of scents, my sensory experiences, and even the vividness of imagination and memory, have become more rich, layered, and powerful.

I will never forget the magic of that first “scent memory”, and now each time I hear Enya’s lush, synth-layered music I imagine the smell of the sea, the sound of seagulls, and feel again enchanted. Sound and scent are so entwined within this memory’s power I cannot imagine one without the other.

Humans tend to imagine senses as discrete channels, but in reality they are interdependent and work together to create our perceptions of the world. Petrichor, or the smell of rain feels deeper when thunder rumbles in our chests; we sense the hum of machinery while cringing from the cutting scent of gasoline. Scientific evidence supports what we intuite: sound and scent co-constitute perceptual fields at both neural and ecological scales. This entanglement, sometimes termed smound, is no simple multisensory trick, but a deep structure of how humans and other organisms derive meaning from their environments. Awareness of these intimate connections between sensory systems can help us not only understand how we perceive our environments, but also how co-designed sensory cues can be used to alter our perceptions, making us feel more safe and connected.

The fact that acoustic and aromatic chemical cues co-evolve is represented broadly in nature. For instance, pollinator’s have developed behaviors in response to coincidence of bird noise and floral volatiles — the smell of flowers — to time their pollen-collecting activity for both opportune time of day and seasonal clocks. Additionally, plants rely on aromatic chemical “signals” of insects paired with the sounds they make, felt as vibration, to identify the difference between approaching predators or potential pollinators; therefore, triggering the release of compounds to either attract or deter the oncoming creatures (Appel, H.M., Cocroft, R.B. 2014); Helms, A., et al. 2017). To step into a forest or meadow is to enter an entangled yet invisible web of olfactory and sonic communication between plants and other species (Ninkovic, V., et. al. 2021). Therefore smound is deeply embedded in ecological communication networks, sometimes in ways so interconnected that without one, synchronicity within the ecosystem would be lost.

As within ecological systems, human communication systems also rely on smound and the fusion of scent-sound within our imagination and memory.

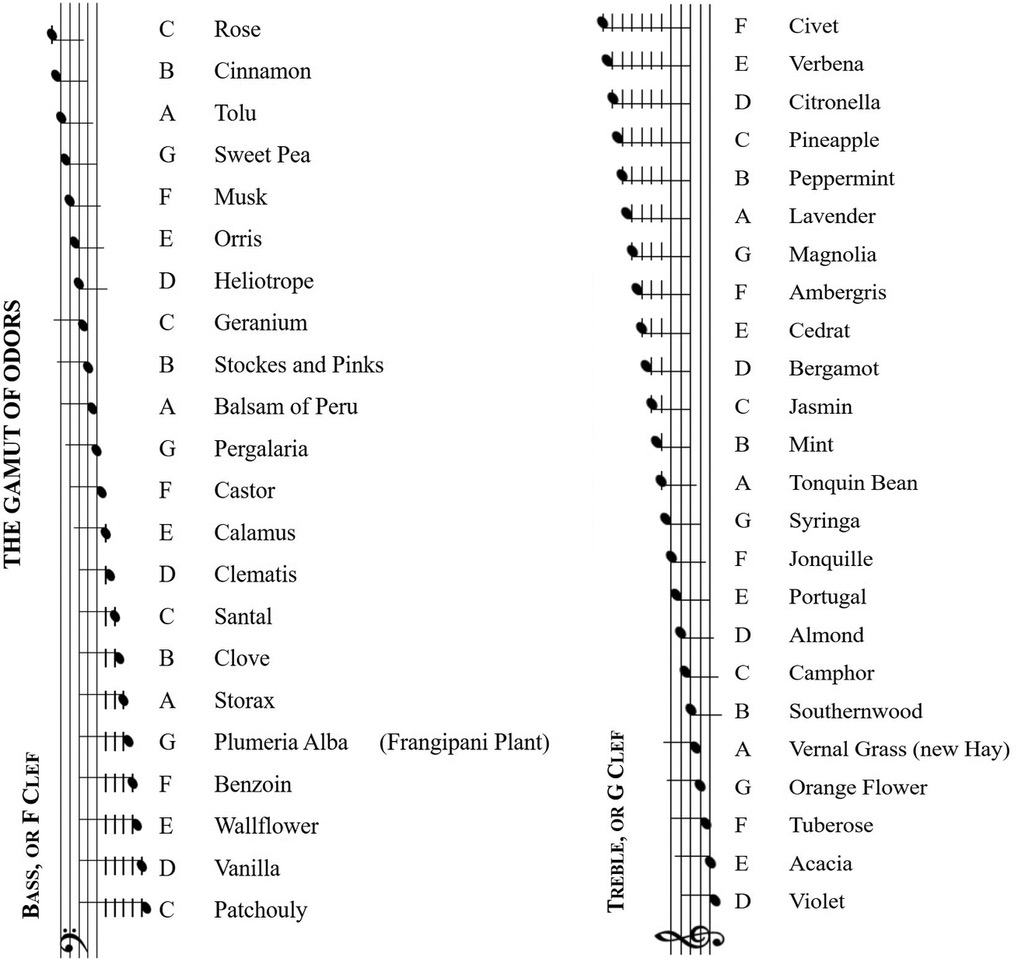

In a written exploration of scent and perception with artist Sissel Tolaas for TED Ideas, Lasky J. (2015) aptly writes: “There is nothing good or bad, but smelling makes it so” (Lasky J. 2015). For years, humans have intuitively used the interplay between our senses to tell stories, build the personality of our homes or brands, and market products and ideas (The olfactory spectrum: matching fragrances to brand colors. 2025). In an emerging field of multi-sensory marketing, chemists and designers to cosmetic companies alike have explored developing “sonic-scents”, or soundscapes designed to correspond to or evoke certain smells. Sound and musical scale even appears in foundational book The Art of Perfumery by Septimus Piesse, as he suggests correspondence between musical notes on a scale and the oder emitted by plants (Spence, C., et. al. 2024; Piesse S. 1867).

Figure from Spence, C., et. al. (2024). Septimus Piesse’s suggested musical note-scent correspondence (1867, pp. 42–43) depicted on a scale.

“There is, as it were, an octave of odours like an octave in music; certain odours coincide, like the keys of an instrument.”

Piesse, S. The Art of Perfumery, 1867

Not only perfume brands capitalize on people’s associations of other senses with smell: imagine entering a Middle Eastern spice and perfume shop. Instinctively, you may recognize shelves lined with deep red carpets and mahogany vials as a place to find “warm” scented spices like cinnamon and cardamom. Perhaps perfume sits in a bowl of sea glass and blue-green stones — even before opening, the bowl’s visual tone hints to smells lighter and fresher than the spice cabinet. Soft string music, a duet between an oud and santur, fill the shop’s atmosphere and mix beautifully with haze from burning incense that smells like earth. This shop is enticing in its congruency. The shop’s owner has intentionally created a sound-scent-sight space to inspire potential customers with a magical, yet expected, experience and make them feel at ease.

Now imagine the same shop, but wander through blue and yellow shelves as punk rock blares from overhead speakers. Would you find the incense as peaceful and warm, or would it jar you or become less noticeable? Would you pick up the spice vials and perfume or leave them unnoticed? Without signage, what kind of shop would you imagine walking in to? Some might find the latter shop intriguing; others, overwhelming. But ultimately, the experience would shift and depending on the seller’s targeted customers, they may lose sales due to the incongruency of the sensory experience.

How does this work? Congruent or “pleasant” sounds, particularly if they fit one’s association to a scent, make odors feel more pleasant. Auditory cues can change how attractive we think a smell is: the reverse is also true. Research in multisensory perception shows that background sound, including environmental soundscapes, can significantly alter the way people evaluate odors — shifting perceived pleasantness, intensity, and emotional valence (the emotional characters that contribute to appeal or repulsion) (Knasko, S. C. 1992). Sounds from nature such as wind, water, and insects particularly shift how we experience plant-derived scents. For instance, a study by Seo H.S. and Hummel T. (2011) found that ambient natural sounds, such as birdsong, water, and rustling leaves increased study participants’ pleasantness ratings of floral scents (Seo H.S. and Hummel T. 2011).

Beyond subjective ratings, there is neurophysiological evidence that the brain synchronizes auditory and olfactory processing. In a study using intracranial electrophysiology, Zhou et al. (2019) found that phase synchrony between low-frequency oscillations in the auditory cortex and piriform cortex, where we process olfactory and taste information, predicted correct cross-modal matching of sound and odor (Zhou, G., et al. 2019). In other words, the mechanisms behind interpreting scent and sound are deeply entwined and affect the internal patterns of our body. This suggests that sensory integration is not only perceptual but rhythmic — the brain aligns neural timing to unify smell and sound. Our bodies are designed to align with and attune to smound. While both are subjective to people’s individual tastes and preferences, sound and scent work together to influence our perception of an object, experience, or environment through cultural and biological associations ingrained within our brains.

Sound-scent research can provide benefit beyond better understanding ecological communication or increased sales and smart perfume marketing. It is well studied that natural soundscapes and scents enhance psychological restoration and positively shift environmental evaluation, or the positivity we feel from the spaces we inhabit. Additionally, sounds like wind in leaves, rain, birds, and other animals consistently increase perceived pleasantness, calmness, and “naturalness” of city environments relative to mechanical or urban noise (Aletta F, Kang J. 2018). However, until now, we have often focused on sound, scent, and other senses in isolate — ignoring the important interplay between them.

While often intuitively felt and shown above in my own smound memory of smelling salt air for the first time, research concurs that scent and sound are major drivers of memory retrieval and sensory bonding with places (Bentley P. R et al. 2022).What if sound was used intentionally to trigger scent associations when aroma is lacking? How does this alter the perception of the experience? What if it could help us feel more at ease or connected to our surroundings and bodies? Some suggest using sound as a way to incorporate scent and smell into virtual environments to enhance user engagement and wellbeing in the sensory depraved spaces much of our lives revolve around (Grimshaw, M Walther-Hansen, M. 2015). Perhaps if our living and working spaces were planned not only with air fresheners and ocean wave playlists, but intentionally designed to expose us to congruent scents and soundscapes of healthy ecosystems rooted in the location’s ecology, we might feel not only more productive and positive in our day-to-day, but also more deeply connected to where we live.

Not only are our perceptions of ecosystems co-created by entanglement of sound and scent: internal environments are also shaped by their interplay. While overlooked in modern society, the relationships between how sensory experiences, particularly driven by natural smells and sounds, shape psychological evaluation of ourselves and the world have been employed for centuries through techniques like aroma therapy and forest bathing. Brianza, G. et. al. found that sound and scent even work together to influence how positively or negatively one perceives their body and how comfortable or uncomfortable we feel within ourselves (Brianza, G., et. al. n.d.). While this area of research remains novel and emerging, smound could be a useful tool in understanding how scents and sounds influence body perception; additionally, sonic-scent interventions could be employed to increase body image positivity and comfort felt within the self. Often, to feel more rooted to a place, whether our landscapes, communities, homes, or bodies, we need to perceive safeness; perhaps in this way, sound and scent entanglements could be used as tools for fostering care and connection across individual to socio-ecosystematic scales.

Smound is more than a sensory curiosity. It can be a framework for designing multisensory experiences, understanding ecological communication, and supporting spaces that make people feel more grounded, connected, and safe. An awareness of the entanglement of sound, scent, and other senses invites us to live more relationally: to listen with our noses, smell with our ears, and approach environments as atmospheric, interwoven fields. In doing so, we open a more attuned, ecological imagination — one where perception deepens belonging.

Willow Gatewood is an environmental scientist, interdisciplinary artist, storyteller, and biophile. Follow her on Instagram @willowg_music.

Sources:

Aletta F, Kang J. (2018). Towards an urban vibrancy model: A soundscape approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health.15(8):1712. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081712. PMID: 30103394; PMCID: PMC6122032.

Appel, H.M., Cocroft, R.B. (2014), Plants respond to leaf vibrations caused by insect herbivore chewing. Oecologia 175, 1257–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-014-2995-6

Bentley, P. R. et al. (2023). Nature, smells, and human wellbeing. Ambio, 52(1), 1–14. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01760-w

Brianza, G., et. al (n.d.). As Light As Your Scent: effects of smell and sound on body image perception. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10073374/1INTERACT_As_Light_As_Your_Scent-finalpublished.pdf?utm

Grimshaw, M. Walther-Hansen, M. (2015). The sound of the smell of my shoes. In Proceedings of the Audio Mostly 2015 on Interaction With Sound (AM ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/2814895.2814900

Helms, A., et al. (2017). Identification of an insect-produced olfactory cue that primes plant defenses. Nat Commun. 8, 337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00335-8

Knasko, S. C. (1992). Ambient odor’s effect on creativity, mood, and perceived health. Chemical Senses, 17(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/17.1.27

Lasky, J. (2015). How smell shapes our perception of the world around us. TED Ideas. https://ideas.ted.com/how-smell-shapes-our-perception-of-the-world-around-us/

Ninkovic, V., et. al. (2021). Plant volatiles as cues and signals in plant communication. Plant, cell & environment, 44(4), 1030–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13910

Piesse S. (1867). The Art of Perfumery and the Methods of Obtaining the Odors of Plants: With Instructions for the Manufacture of Perfumes for the Handkerchief, Scented Powders, Odorous Vinegars, Dentifrices, Pomatums, Cosmetics, Perfumed Soap, Etc., to which is Added an Appendix on Preparing Artificial Fruit-essences, Etc. Lindsay & Blakiston. https://books.google.com/booksid=meQPAAAAYAAJ&ots=8BY_gLugLq&lr&pg=PA13#v=onepage&q&f=false

Seo H.S., Hummel T. (2011). Auditory-olfactory integration: congruent or pleasant sounds amplify odor pleasantness. Chem Senses. 36(3):301-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjq129. Epub 2010 Dec 16. PMID: 21163913.

Spence, C., et. al. (2024). Marketing sonified fragrance: Designing soundscapes for scent. I-Perception, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20416695241259714 (Original work published 2024).

The olfactory spectrum: matching fragrances to brand colors. (2025). Colorlabs.net. https://colorlabs.net/posts/the-olfactory-spectrum-matching-fragrances-to-brand-colors

Zhou, G., et al. (2019). Human olfactory-auditory integration requires phase synchrony between sensory cortices. Nat Commun 10, 1168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09091-3.

Plantings

Issue 54 – December 2025

Also in this issue:

Rooted Resistance: Rashid Johnson’s Potted Plants as Living Symbols

By Gayil Nalls

Is There Such a Thing as Too Many Houseplants?

By Molly Glick

The Female Artist Who Showed How Plants and Insects Relate

By Alice Alder

Jane Goodall: A Voice for the Planet

By Gayil Nalls

The Scents of Christmas: Aromatic Plants, Memory, and the Ecology of Celebration

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Winter’s Jewels

By Laura Chávez Silverman

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.