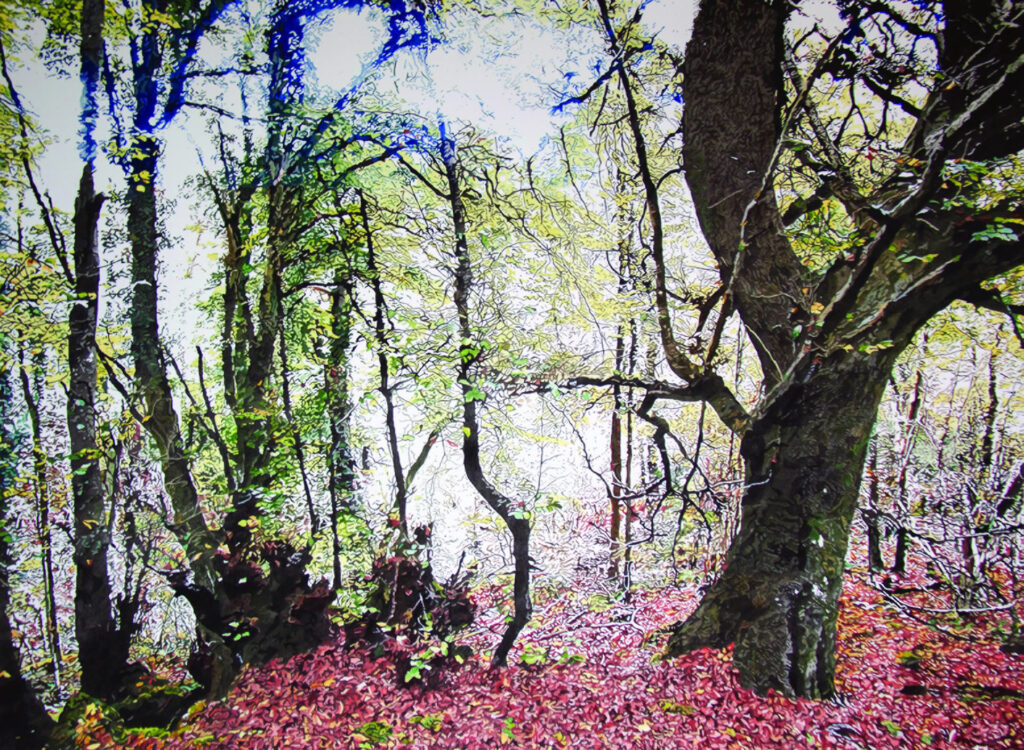

The Arborealists: Tree Painters from the United Kingdom

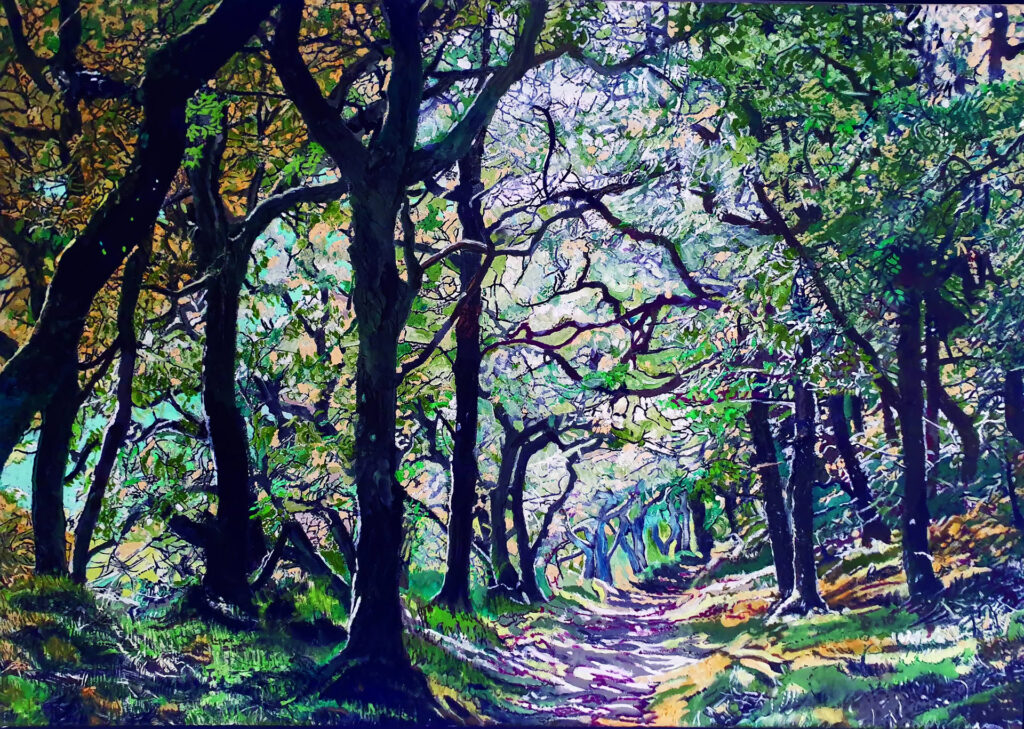

Bageworthy Ancient Woodland, Exmoor

Oil on canvas, 90 x 160 cm

By Philippa Beale

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

To paraphrase Henry James: an artist is someone who wants to share his vision with others—and The Arborealists, a group of professional artists who feature trees as the central aspect of their practice, certainly want to share theirs. Since their formation in 2014, they have held over forty exhibitions, establishing a strong international profile. The Arborealists differ from other painters of trees in that they have always been involved in site-specific projects.

In 2016, George Peterken OBE, forester, ecologist, and author, invited the group to respond to Lady Park Wood near Monmouth, the only scientifically monitored and unmanaged woodland in the United Kingdom. The film Lady Park Wood, produced by Fiona McIntyre, was screened throughout Europe, showing the Arborealists on the ground, collecting information firsthand.

As part of HM Queen Elizabeth II’s Green Canopy Project, the group chronicled the ancient trees of England in a collaboration with Julian Hight, presenter and judge of Channel 4 TV’s Tree of the Year and Chair of the Ancient Tree Forum. This resulted in an ongoing exhibition partnership, From Ancient Trees, at Nature in Art Gallery, a museum and art gallery at Wallsworth Hall, Twigworth, Gloucester, England—dedicated exclusively to art inspired by nature in all its forms. The museum has twice been specially commended in the National Heritage Museum of the Year Awards. The current director, Simon Trapnell, became a ‘friend’ of the Arborealists and a key speaker at their second conference, held at the Turner Gallery in 2023.

Since 2018, the Arborealists, in partnership with Katrina Munro, Sustainable Economy Officer at the Exmoor National Park Authority, have worked on two areas of great national significance: Dartmoor and Exmoor. This collaboration culminated in 2020 with a major exhibition, beginning at the Somerset Museum and Art Gallery and travelling to venues throughout the West of England during 2021 and 2022.

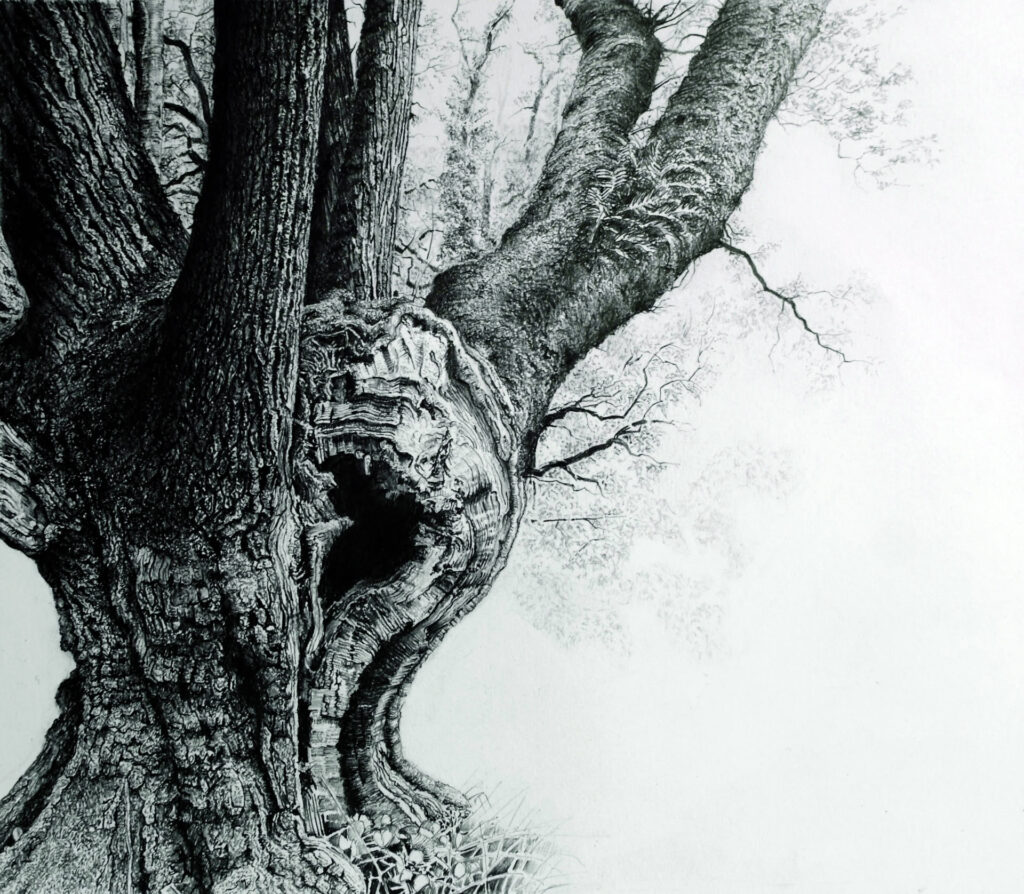

The Tree that’s not the Tree from the Tree

Beech Charcoal, carbon stick, and white conté on paper, 59 x 84 cm

George Peterken OBE

In the summer of 2016, George Peterken OBE, celebrated expert and author on trees and natural woodland, was on holiday. Cycling through Lymington—the main town in the New Forest—he stopped at a red light and spotted a tiny advert tied with string around the pole of the Belisha beacon. It advertised an exhibition, The Art of the Tree by The Arborealists, at St Barbe Museum & Art Gallery, Lymington’s major museum.

He knew of these artists, having bought a copy of Under the Greenwood (2013, Sansoms: Craven T., Marshall S.) the year before, and knew he should check it out. If the lights had been green, he would not have stopped. “Of such moments are collaborations made.”

The coming together of the ecologist and the artists was completely serendipitous. A glance at a pedestrian crossing in Lymington High Street, in the famous New Forest—planted by William the Conqueror from 1068—kickstarted the Arborealists’ first site-specific project, which would open many doors for them in the future

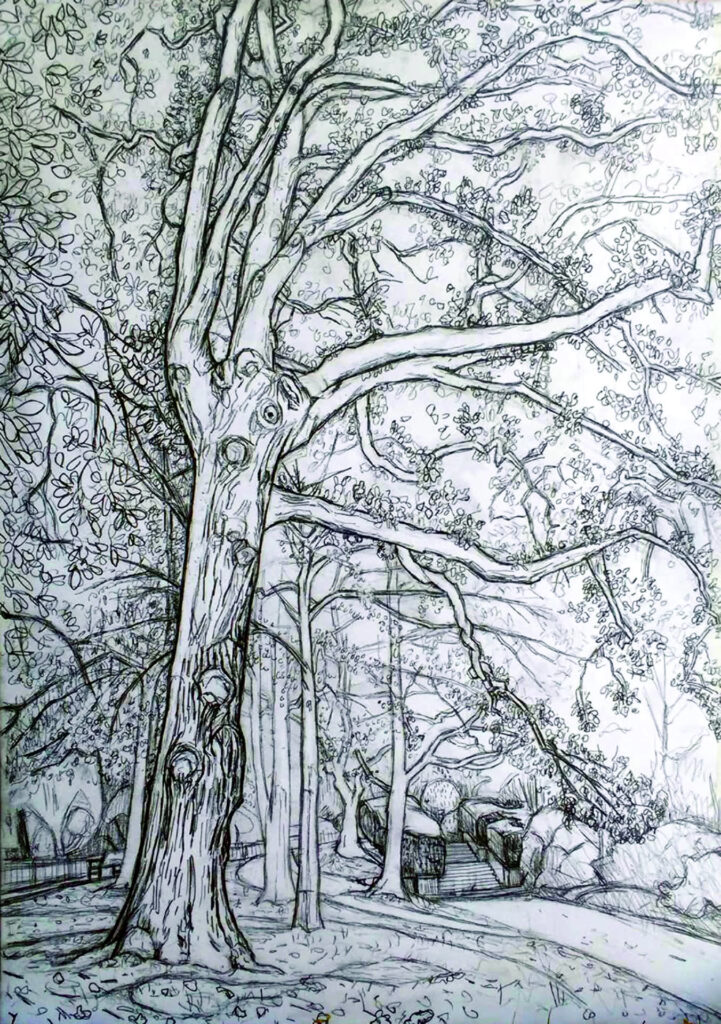

Holland Park Oak (2018)

Pencil on paper, 42 x 29.8 cm

Horner Wood, Exmoor (2020)

Oil and acrylic on gessoed board, 60 x 40 cm

The Arborealists’ interaction with a woodland specialist from a scientific background—who recognizes that art offers alternative ways of observing and understanding woodlands—has been of immense importance in developing the group’s ethos. George Peterken says that the work the Arborealists undertake in woods and forests contributes significantly to ecological studies and wildlife conservation, as well as attracting a wider audience. For instance, the six thousand volunteers from The Tree Council of Great Britain, as well as the general public, help expand the message about the importance of woodlands and their future protection.

The first project undertaken (in collaboration with Mr. Peterken) was Lady Park Wood, an ancient woodland in the gorge of the lower Wye Valley, which has been the focus for over 80 years on how to study natural woodland.

These interactions and on-the-ground investigations produced not only paintings for exhibitions but also conversation and debate, which are accessible in a series of publications—one being Lady Park Wood: Art Meets Ecology (2020, Sansom: Craven T., Payne C., Peterken G., Rainsbury A., editor Kay A). The works created in the wood are linked to commentaries setting out understandings gained from 80 years of ecological research.

Peterken points out that while these woods appear natural to the casual observer—and their obvious lack of management gives the visitor a sense of freedom and even danger—historical records show that they have been greatly influenced by human activity. For example, Lady Park Wood was managed as coppice until 1870, supplying charcoal as part of the local economy. It only appears as it does today because selected areas have remained untouched since coppicing ended and the wood was designated in 1944 as a place to study the unfettered growth of native woodland.

October Frieze, Lady Park Wood

The Lady Park Wood project was followed by extensive surveys across Dartmoor and Exmoor, including the renowned Bageworthy Wood in Exmoor and Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor. Expertise from National Park Authorities and ecologists, plus local knowledge, enabled the artists to identify ancient trees and woodland sites of particular ecological, social, and historical significance.

The latest survey, also introduced to the group by Peterken, is centered on an area called Staverton Thicks, located in the Suffolk Sandlings. It will culminate in an exhibition at the famous Minories Gallery in Colchester, Essex, in 2026.

Peterken also reminds us that Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor is not a remnant of primeval Britain, as analysis of ancient pollen shows that 500 years ago it was open shrubland with no sessile oaks. As Philippa Beale suggested, the trees were probably felled in ancient times to allow for more efficient grazing (The Art of the Tree, 2016, Sansoms & Co: Beale P., Craven T., Davies P., Marshall S., Summerfield A.).

The project centered on Staverton Park in Suffolk—one of the oldest forests in the UK—focuses on Staverton Thicks, developed only in the past 220 years when parts of the park were enclosed. However, the park’s medieval oaks have not changed much and would still be recognizable to those who enclosed it 800 years ago, and also to the governing elites who hunted there in the early 16th century, including King Henry VIII.

While most visitors believe these woods to be unchanging—a contrast to the ubiquitous urban environment and manicured farmland—this belief is largely false. These are not untouched vestiges of Paleolithic Britain, but landscapes shaped by continuous human influence.

The Ethos and Polemic of the Arborealists

The Arborealists emerged after Under the Green Wood, an exhibition curated by Steve Marshall and Tim Craven at St Barbe Museum and Art Gallery in Lymington, in the New Forest, Hampshire. Tim Craven had the idea to create a movement of tree painters, and part of his discussions with artists included telephoning Philippa Beale in France. During this call, she came up with the name. They agreed on it because, being of Latin origin, it easily translated into many languages. At that time, the artistic climate favored film/video, photography, and installation, which were ubiquitous in galleries and museums. Tim and the founding members wanted to elevate painting.

If you were to ask why the Arborealists came into being, beyond wanting to exhibit, their reasons are political. From Banksy engaging the ‘man in the street’ to the black paintings of Goya, all art is political. For the Arborealists, their polemic is to contribute to the preservation of our planet and fight to address deteriorating ecosystems by exhibiting artworks of trees to raise public awareness. More trees create more habitats and biodiversity for everything from insects to birds, from bats to fungi. Planting native trees and plants offers shelter to native species. By creating images of these environments, the artists in the Arborealists contribute to restoring areas degraded by human activity by engaging with their audience and encouraging them to support their local woodland.

While many of the Arborealists were with George Peterken collaborating in Lady Park Wood on the first survey, not all could participate, as at the time there was urgent work to be undertaken documenting the felling of millions of trees in southwest France that stood in the path of a new railway line—the Ligne à Grande Vitesse from Paris to La Rochelle. The laying of the line created a scar across the face of the Aquitaine, which can still be seen today when flying into Poitiers Airport. At the time of writing, the LGV from Paris to La Rochelle operates only four times a week. The devastation caused by bulldozing vast tracts of woodland impacted heavily on the mainly agricultural community and very negatively on the wildlife, and the inhabitants didn’t even get the rail station they were promised. Thanks to the Arborealists involved, images of those desecrated woodlands now exist as paintings.

Research undertaken by the Arborealists shows that depleted woodlands lead to a diminution of biodiversity, and while artists and ecologists observe trees differently, each group expresses its understanding of woodland in very different terms.

The Arborealists seek to serve as a conduit, aiming to explore and deepen understanding of each other’s activities through collaboration to promote a broader interest in native woodlands.

Elm and ash disease, the great drought of 1976, plus storms and flooding have imposed a heavy toll on the United Kingdom’s ageing beech, oak, lime, ash, yew, and hazel. And while they lie in great heaps of dead wood, interestingly, such devastating images inspire some Arborealists to capture the aftermath in paint.

Study for Edge of Arcadia (2016–22)

Oils on canvas

100 x 100 cm

Arborealist exhibitions aim to create a ripple effect, reaching out to touch communities and encouraging them to engage in conservation. This kind of action mirrors the thinking of Richard Buckminster Fuller, the American architect, philosopher, and systems theorist, who said: You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

The Arborealists have created new models for artistic engagement with nature, providing opportunities for artists to work alongside experts and specialist organizations. They have built a compendium of original artworks that emerged from studying natural woodlands, which they have exhibited in museums in France, Gibraltar, and across the United Kingdom.

There is a consensus within the group that fostering a personal connection to nature is vital to awaken and mobilize a predominantly urban population that has become separated from its primordial roots. Our instincts, particularly in times of crisis, are soothed by images that assuage the pain, grief, and doubt we experience at such moments. Much of the population shares our concerns; they feel disconnected from nature due to the constraints of modern living. While there are no simple solutions, the Arborealists strive to provide the public with visual experiences that help them reconnect with trees and nature.

Cloutsham Ball oak, Exmoor

With over 40 members, the Arborealists’ diverse and influential practices place a spotlight on the history and transformation of protected woodlands and express new perspectives on how art can illuminate the enchantment of ancient trees. Every member has developed a personal visual language, showcasing variations in scale, medium, style, and philosophical approach.

In their first ten years, the group has mounted over forty successful exhibitions, garnering widespread critical acclaim. The Arborealists are continually exhibiting at one venue or another. Their current year-long exhibition, The Quietness of Feeling, runs from October 2024 to September 2025 at Portsmouth Museum and Art Gallery, Hampshire, England. Biofilia, curated by member Paul Newman, Arts Director of Sherborne Arts Centre, Dorset, has created two-month-long interventions in hospitals across the West of England, namely Dorchester and Bath in Somerset.

End of Winter

Oil on panel, 44 x 38 cm

The tree, as a subject for art, is endlessly versatile. Consequently, the artists belonging to the Arborealists create a wealth of different interpretations. The practice of site-specific interventions—where a distilled focus, considered over time, is shared with the public—is an integral strand, the trunk, if you will, of the Arborealists’ ethos.

Philippa Beale, Margate, Kent, England, is an artist and educator who has curated exhibitions across the UK, France, and Gibraltar for over two decades. Elected a Fellow in Fine Art for Higher Education in 2006, she has taught at leading art schools in the UK, France, and Australia.

Dr. Beale is the author of Forests, Woods, and Groves, published by Batsford.

NOMINATED FOR THE WAINWRIGHT PRIZE 2025

Available to buy in all good bookshops and on Amazon.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.

Plantings

An Existential Reflection on Plant Intelligence

By John Steele

Schilthuizen’s Darwin Comes to Town, and You Too Should Join Him

By Caterina Gandolfi

“Small Is Beautiful”: A Conversation with Renate Christ on Climate, Culture, and What We Stand to Lose

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Chopped Salad with Lime Dressing

By Gayil Nalls