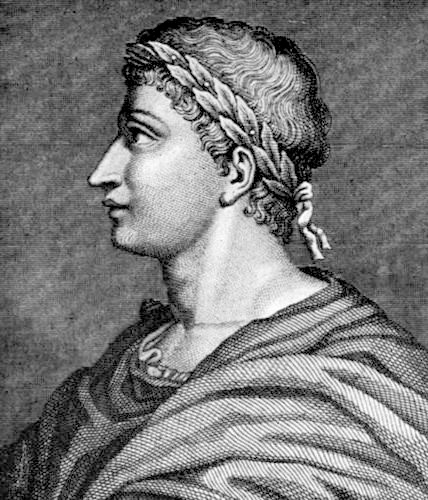

Maksim, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The Crown Made of Leaves

By John Steele

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

The laurel enters human history not as an idea but as a fact of observation. It keeps its leaves when other trees let go. In the Mediterranean winter, when orchards stand bare and fields retreat into the earth, the laurel remains green. This is not a flourish; it is a condition. For people whose lives were governed by seasons and whose survival depended on reading the land accurately, such persistence was not decorative. It was instructive.

The ancient world did not treat nature as neutral scenery. Plants, stones, animals, and stars were read as evidence of how the world behaved. The laurel’s endurance suggested that continuity was possible without force, that survival did not require dominance. Its leaves were tough, aromatic, slow to decay. When cut back, the plant responded by growing again, denser and stronger. These were not metaphors imposed from above; they were conclusions drawn from experience.

Before the laurel-crowned human achievement, it marked human space. Branches were hung in homes and temples as a form of protection, not ornamentation. They signaled that something set apart was happening here, that this was a place where disorder was to be kept at bay. The laurel’s resistance to decay translated naturally into a belief that it could guard against corruption, whether physical or moral. Meaning followed function.ving systems, which is itself linked to well-being and longevity.

Myth arose from the same impulse to explain. The story of Apollo and Daphne is often reduced to pursuit, but its lasting force lies in transformation. Daphne escapes possession not by overcoming Apollo, but by changing form. She becomes a tree—rooted, enduring, unavailable. Apollo does not undo this act. He accepts it and binds himself to its outcome. By declaring the laurel sacred, he acknowledges a limit to power.

This is a quiet but radical moment. The laurel becomes a symbol not of conquest, but of restraint. It carries within it the memory of refusal, preserved without bitterness. The Greeks understood that not all victories involve taking, and not all achievements are measured by control. By associating the laurel with Apollo, they placed it at the center of disciplines that require patience: music, poetry, prophecy. These are arts that unfold over time, shaped by discipline as much as inspiration.

The wreath itself reinforced the lesson. Made of living leaves, it would dry and crumble. Honor was real, but temporary. Excellence was recognized, but not embalmed. Achievement, the laurel implied, must be sustained or it fades. Glory is a moment; practice is a lifetime.

Rome inherited this symbolism and applied it to power. Generals wore laurel wreaths in triumph, yet the plant quietly contradicted the spectacle. Amid gold and ceremony, the laurel reminded the victor that endurance mattered more than display. The moment would pass. What remained was the substance of what had been done. Even in celebration, the laurel carried a warning against excess and forgetfulness.

The plant itself supported these ideas. Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) thrives in poor soils and dry climates. Its leaves contain oils that repel insects and slow spoilage. Long before chemistry named these properties, people used them. Food stored with laurel lasted longer. Textiles and manuscripts survived pests. The laurel did not merely symbolize incorruptibility; it enacted it. In a world constantly threatened by rot and loss, this mattered.

Language absorbed the lesson. To be a laureate was to have earned recognition through sustained effort. To rest on one’s laurels was to risk decline by mistaking past achievement for present work. The phrase assumes that success, like a plant, must be tended or it will wither. Even the evergreen sheds leaves.

What distinguishes the laurel from other ancient symbols is what it refuses to celebrate. It is not a monument to strength or domination. It does not glorify violence. It honors mastery, continuity, and renewal. It values time over spectacle. In this, it proposes a different measure of human success—one rooted in endurance rather than conquest.

The laurel survives today mostly as metaphor or seasoning, its ancient meanings half-remembered. Yet the ideas it carries remain intact. We still admire achievements that endure without hardening, that renew themselves without losing form. We still understand, instinctively, that the most lasting work is done quietly, through attention and care.

The laurel is a collaboration between nature and human understanding. The plant offered its properties—evergreen leaves, resilience, resistance to decay. Humans supplied interpretation. Together they produced a symbol that has lasted for centuries without becoming empty. It speaks of excellence without arrogance, victory without destruction, memory without fixation.

In the end, the laurel does not promise permanence. It offers something more realistic and more demanding: continuity through renewal. It suggests that what lasts is not what resists change, but what adapts without losing integrity. In a green leaf held against winter, the ancients found not an escape from time, but a way to live within it.

John Steele is the publisher and editorial director of Nautilus Magazine.

Plantings

Issue 56 – February 2026

Also in this issue:

Urban Nature: Building Resilience with Living Systems

By Gayil Nalls

Why the World Must Measure Well-Being, Not GDP

By Gayil Nalls

The Secret Lives of Tree Roots

By Kristen French

Becoming the Sea: Anselm Kiefer and the Mississippi as Memory, Material, and Warning

By Gayil Nalls

On Self-Incompatibility

By Daria Dorosh

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Why and How to Grow Microgreens

By WS/C

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.