Photograph by Gayil Nalls

The Healing Instinct: Plants, Animal Behavior and the Origins of Medicine

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

L ast month, I observed a fascinating interaction between my dog and a neighbor’s aging companion, Juno. My dog, who often has his nose in a plant, was grazing on specific grass species, seemingly in an attempt to soothe his intestinal discomfort. Later that morning, I watched Juno, a white-faced senior dog, delicately eat a small amount of yarrow (Achillea millefolium) while my dog curiously observed. My dog then sniffed and licked the flower but ultimately chose not to eat any.

Yarrow, well-known to humans for its medicinal properties, has been used for centuries as a digestive aid and mild astringent, often to treat diarrhea. The plant contains compounds like flavonoids and sesquiterpene lactones, which help reduce inflammation. However, veterinary medicine suggests that the same sesquiterpene lactones can sometimes exacerbate gastrointestinal issues in dogs and may even cause neurological symptoms, particularly in those sensitive to the plant.

The observation of animals interacting with medicinal plants is not uncommon. Cats, dogs, wolves, and even bears have been known to consume specific grasses and plants when experiencing digestive distress or infections. These plants are thought to act as purgatives or anti-inflammatories. This instinctive behavior is known as zoopharmacognosy—the act of animals self-medicating through natural substances found in their environment.

Zoopharmacognosy is an extraordinary phenomenon seen across the animal kingdom, illustrating that animals possess an innate ability to treat their own ailments. One particularly striking example comes from recent research on an orangutan in Sumatra. This individual, named Rakus, was observed creating a poultice from medicinal plants to treat an open wound on his face. The observation, published in Scientific Reports and Nature, marked the first scientifically recorded instance of a wild animal using known medicinal plants to heal itself in this way. Rakus chewed specific leaves without ingesting them and used his fingers to smear the resulting juice over his wound for about seven minutes. Remarkably, he repeated the treatment the following day, and just over a week later, the wound had fully healed.

This behavior of self-medication is also seen in many other species. For example, Canadian geese are known to consume particular leaves to expel tapeworms, while dusty-footed woodrats line their nests with aromatic plants such as gnawed bay leaves that act as fumigants, keeping parasites at bay. In Kenya, pregnant elephants have been observed eating the leaves of Boraginaceae plants to induce labor, likely due to the uterine-stimulating properties of the plant’s chemicals.

Such examples highlight that animals rely on a combination of instinct, learned experience, and environmental cues to identify plants that can aid in their healing. This behavior underscores a deep, evolutionary connection between animals and their natural environments, revealing sophisticated methods of health regulation that extend far beyond basic survival.

The healing instinct observed in animals has deep roots in the natural world, and it is believed to have significantly influenced early human knowledge of herbal medicine. Our ancestors, living closely with nature, likely noticed how animals would seek out specific plants to alleviate their ailments. This innate behavior, passed down through generations of animal species, served as a form of natural wisdom for humans to tap into. Indigenous cultures across the globe have long relied on such observations to guide their use of plants in treating a wicncnde range of disorders. The behavior of animals, particularly in their selection of medicinal herbs, became an early blueprint for developing remedies that would later evolve into the sophisticated practices of herbalism and modern pharmacology. This close connection between animal behavior and human medicine underscores a shared biological intelligence—one rooted in survival and the healing power of nature. Today, zoopharmacognosy continues to inspire scientific research, reaffirming that the animal kingdom holds untapped knowledge of medicinal plants that may benefit both human and veterinary medicine.

This intersection of nature and science continues to offer insights that could lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic approaches, shaped by the power of plants and the wisdom of the animal world.

Dogs sometimes eat grass as part of a natural behavior, often for self-medicating or digestive relief. While many grass species are safe, some are better suited for dogs to nibble on without causing harm. Here are grasses that are both safe and beneficial for dogs:

Wheatgrass (Triticum aestivum) is rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, wheatgrass is often used in pet supplements. It can aid digestion, improve metabolism, and provide a nutritional boost.

Barley Grass (Hordeum vulgare) is a nutrient-dense with high fiber content, barley grass helps support digestion and is safe for dogs to eat in moderation. It may assist with stomach upset or constipation.

Oat Grass (Avena sativa) is easy to digest and contains vitamins A, B, and C, making it a healthy choice for dogs. It can soothe digestive issues and is gentle on the stomach.

Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) is known for its calming effects, lemongrass can help with digestive problems. However, it should be offered in small amounts, as large quantities might cause stomach upset.

Bamboo Grass (Phyllostachys spp.) is non-toxic to dogs and can be eaten safely. Dogs sometimes chew on bamboo leaves, which contain some fiber and may help with digestion.

Rye Grass (Lolium perenne) is not nutrient-rich like wheatgrass or barley grass, but is safe for dogs to nibble on when they are trying to soothe an upset stomach.

Fescue Grass (Festuca spp.) is safe and non-toxic for dogs, fescue is commonly found in lawns and can be eaten without harm when dogs graze on it.

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D., is the creator of World Sensorium and founder of the World Sensorium/Conservancy.

References

Vaidyanathan, Gayathri, Nature, Vol 629, 23 May 2024, p.737

Greene, Alexander, et al. Asian elephant self-medication as a source of ethnoveterinary knowledge among Karen mahouts in northern Thailand. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32387460/

The Proposed Mechanism of Leaf-swallowing and its Effect on Infection https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-proposed-mechanism-of-leaf-swallowing-and-its-effect-on-infections-with_fig2_225938467

Krieger, Marilyn. Dusty-Footed Woodrats Help Save a Canyon

Plantings

Issue 41 – November 2024

Also in this issue:

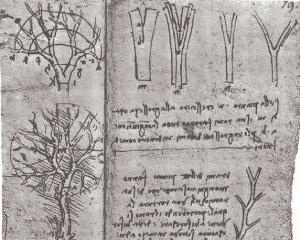

Branching Beyond Leonardo: The Evolution of Tree Architecture Theory

By Gayil Nalls

Will Plants Grow on the Moon?

By Tom Metcalfe

The Art of the Brew: Exploring Beer’s Aromas, Flavors, and Sustainability

By Gayil Nalls

How Can We Make A Better Concrete Jungle

By Gayil Nalls

Cementing Change: How Ginger Dosier’s Biomason is Paving a Greener Path

By Erum Azeez Khan

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Vegetable Tian

By Chef Romain Delacretaz, Table Marine, Nice, France

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.