The Scents of Christmas: Aromatic Plants, Memory, and the Ecology of Celebration

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

According to the Pew Research Center, 90% of Americans say they celebrate Christmas. In December, long before bells ring or lights flicker to life, it is scent that first signals the Christmas season. Before there is color, before there is sound, there is aroma: the sharpened green of conifers, the resinous sweetness of frankincense, the warm spice of clove-studded oranges, the whisper of cinnamon in a kitchen bustling with expectation. These fragrances, some ancient and some newly invented through ritual and repetition, form a sensory tapestry that binds generations to the season. They remind us that the holidays, at their most elemental, are botanical.

Across the world’s cultures, winter celebrations have always leaned on the aromatic gifts of plants to conjure warmth, hope, and continuity in the darkest weeks of the year. Long before Christmas existed as a global holiday, evergreen boughs, incense resins, and seasonal spices were used to protect, purify, and bless households. Today, these traditions persist, sometimes knowingly, sometimes unconsciously—through the sensory cues that define the season. An example of the enduring draw of history, spectacle, and collective ritual is the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree—where approximately 125 million people visit each year.

The scent of evergreen is perhaps the most universal aromatic signal of the holiday. Whether pine, spruce, or fir, these trees emit terpenes that stay vibrant even in winter: crisp α-pinene, citrusy limonene, and balsamic β-pinene. In cold air, these molecules travel lightly, carrying their message of endurance. In many cultures, evergreens were kept indoors as a reminder that life persists even when the landscape sleeps.

The modern Christmas tree continues this lineage, transforming a living botanical symbol into the centerpiece of celebration. Its fragrance fills a home with the reassurance that light will return, that the year will turn, and that we are part of an older, deeper cycle of renewal.

No aromatic plants have traveled farther in the winter imagination than frankincense and myrrh. Harvested from Boswellia and Commiphora trees of the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, these resins were prized across ancient worlds for their medicinal, ceremonial, and spiritual properties. They are among humanity’s earliest aromatic archives.

Burning frankincense releases olibanum—a fragrance that is both citrus-like and grounding—while myrrh carries darker, honeyed, slightly bitter notes. Together, they create a meditative atmosphere, one that has infused rituals for millennia. The biblical story of the Magi carrying these resins to mark the birth of Jesus is not only symbolic but botanical: these plants represented the rarest expressions of healing, kingship, and devotion. Few aromatic plants carry as much cultural, medicinal, and symbolic weight through the ages as frankincense (Boswellia spp.) and myrrh(Commiphora spp.). Revered for over 5,000 years across Africa, Arabia, and the Mediterranean, these sacred resins were once considered more precious than gold—not for their rarity alone, but for their profound therapeutic properties. Modern science is now confirming much of what ancient healers long understood: frankincense and myrrh are botanicals of exceptional healing power. Today, their relevance endures. Many families light resin incense on Christmas Eve, connecting the present to the past through the soft plume of a living aromatic heritage.

If evergreens evoke the forest and resins evoke the sacred, then spices are the heart of domestic ritual. Cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, allspice, ginger, and cardamom—these are the molecules of comfort, warming both body and memory.

Cinnamon, with its cinnamaldehyde-bright heat, traces its cultural significance back thousands of years to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. Cloves, once more valuable than gold, traveled from the Maluku Islands into nearly every winter tradition—from mulled wine in Europe to spiced sweets across South Asia and the Middle East. Oranges, studded with clove buds, become both decoration and diffuser, a glowing embodiment of winter’s optimism.

These scents are nostalgic signals that remind us of the global botanical histories that shape our seasonal rituals. Every holiday kitchen is, in a sense, a microcosm of ancient trade routes and ecological entanglements.

The two best-known species of Mistletoe are Viscum album (European mistletoe) and Phoradendron species, such as Phoradendron leucarpum (American mistletoe).

The custom of kissing under the evergreen mistletoe, with its green and herbal scent, began in ancient pagan traditions, where the plant symbolized love, fertility, and protection. In 18th-century England, this evolved into a festive game: a man could kiss a woman standing beneath a mistletoe sprig, plucking a berry for each kiss until none remained. The practice peaked in Victorian times, and today it survives as a lighthearted, romantic nod to its centuries-old origins.

Christmas is often spoken of as a season of memory and of hope: childhood echoes, family rituals, moments of togetherness, and scents that reawaken us. Aromatic molecules activate the limbic system, the seat of emotion and stored experience. They trigger embodied recollection, linking us to people and places we may no longer be able to touch.

This, perhaps, is why aromatic plants hold such power during the holidays. They do not simply mark the season—they carry it.

As we breathe in the fragrance of the tree, light resin on a cold night, or simmer spices in a warm kitchen, we participate in an ancient sensory lineage, one that crosses continents and centuries. These scents remind us that the world’s aromatic plants are botanical resources that are expansive in our lives as cultural inheritances, ecological sentinels, and emotional anchors.

This holiday season, may we celebrate the plants that make the season vivid—and may we commit to ensuring that future generations can know these scents not as artifacts, but as living, breathing companions on the journey toward a more fragrant and biodiverse world.

Gayil Nalls, PhD, is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist and the founder of the World Sensorium Conservancy.

.

Plantings

Issue 54 – December 2025

Also in this issue:

Rooted Resistance: Rashid Johnson’s Potted Plants as Living Symbols

By Gayil Nalls

Is There Such a Thing as Too Many Houseplants?

By Molly Glick

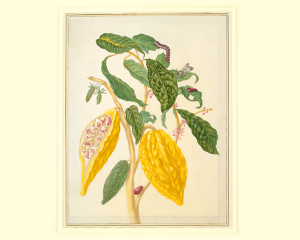

The Female Artist Who Showed How Plants and Insects Relate

By Alice Alder

Smound: how entanglement of scent and sound shape our world

By Willow Gatewood

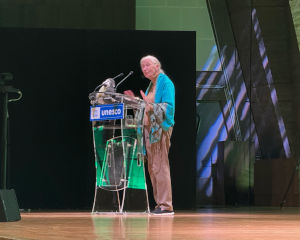

Jane Goodall: A Voice for the Planet

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Winter’s Jewels

By Laura Chávez Silverman

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.