Viriditas: Musings on Magical Plants

Galanthus spp.

By Margaux Crump

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Standing at the last edges of winter, I always look forward to spring. The cascade of color, the scent of flowers, the warmth of the sun on bare skin; my body eagerly anticipating the seasonal surge of dopamines, itching to peel off my hibernation. But this year was different. I wasn’t ready to emerge. I didn’t want to leave the sleepy quiet of the colder months or quicken my pace to meet the urgency of spring. I was depleted and foggy. So I dug in my heels and attempted to cultivate presence, to slow down and perceive the borderlands between the seasons. Lingering here, I began to feel spring vibrating just below winter’s surface. Like the energy of a swarm of bees held within a single seed. It undulated, edging closer and closer to the moment when the spring bulbs would crown, rupturing winter with their bright green shoots. It was in this liminal time that I noticed Galanthus rousing from her underground slumber, the winter harbinger of spring, blooming alone in an ornamental garden.

Galanthus is an herbaceous perennial with a single bell-shaped white flower and two slender leaves. Typically, the flower has three outer tepals and three smaller inner tepals, each forming a circle. The outer tepals are thermotropic, opening for pollinators when the weather is warm enough and closing when it is too cold. The inner tepals have distinctive green marks which function as both nectar guides and photosynthetic organs rich with chlorophyl.1 These markings (usually green, but sometimes yellow or peach) help galanthophiles and taxonomists distinguish between the twenty known species and numerous hybrids and cultivars—it is variously held that there are anywhere from 500 – 1500 named varieties. Galanthus make themselves at home in cool mountainous regions with moist soil, originating throughout Europe and the Middle East, from the Pyrenees across to the Caucasus and Iran, then down to Italy, the Peloponnese and Syria.

Galanthus is neither native nor naturalized where I live. Our climate is too warm for her, so I didn’t grow up familiar with her cold-hardy fortitude. And in this regard, she is remarkable. With most varieties blooming from late January to mid-March, Galanthus can flower while the ground is still hardened under a blanket of snow and when the temperatures continue to drop below freezing. She is elegantly equipped to do so. Utilizing energy stored in the bulb, Galanthus sends up leaves with hardened tips to pierce the frost layer. Once above ground, she withstands sub-zero temperatures using anti-freeze glycoproteins in her sap that inhibit the formation of ice crystals. In these conditions, her tissues will collapse but remain undamaged, reviving when the weather warms up enough for the sap to flow once again.2 It is often repeated that Galanthus can even create her own heat through thermogenesis, raising her body temperature to melt the surrounding snow, though this has yet to be proven scientifically.

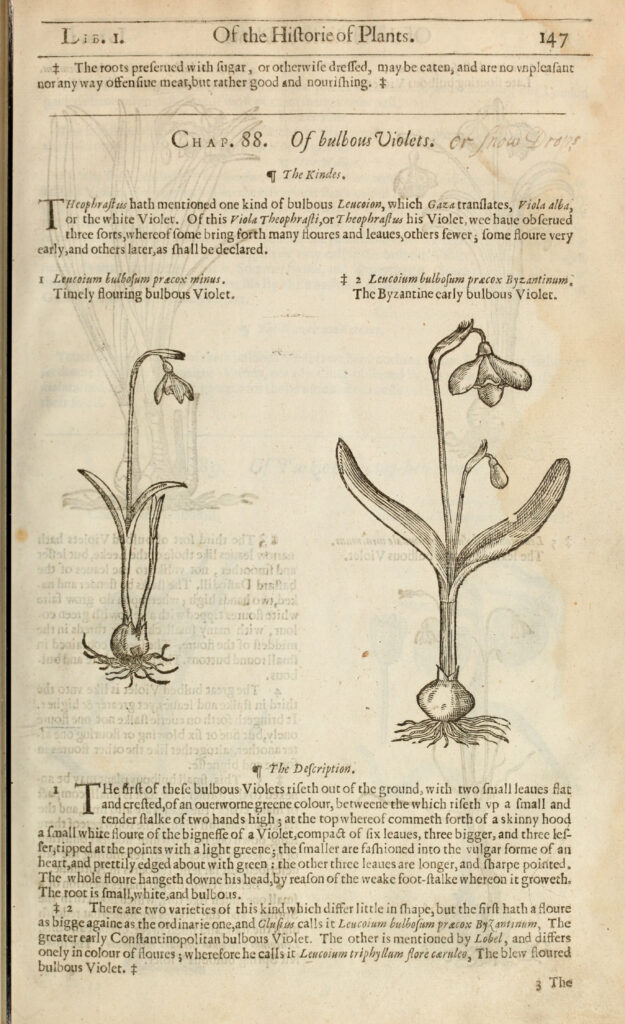

Snowdrop, Fair Maids of February, Eve’s Tears, Mary’s Tapers, Candlemas Bells. Galanthus has been blessed with many, many names over the years and the history of her monikers is quite murky.3 In 1753, the botanical systematist Carl Linnaeus gave Galanthus her generic name from the Greek gala meaning milk and anthos meaning flower. In 1597, the herbalist John Gerard described her as the “timely flowering bulbous violet” and noted her dutch name which he translated as Sommer fooles.4 In 1663, her most common English name, snowdrop, first appeared in Thomas Johnson’s revised edition of Gerard’s Herball, which also suggested she was the same plant as Theophrastus’ Leukoion from his Historia Plantarum (c. 350–287 BCE).5 However, Dioscorides writes that the flowers of Leukoion may be white, yellowish, azure, and purple, which does not match Galanthus’ morphology.6 In an attempt to trace her further into antiquity, researchers have proposed that the herb moly used by the sorceress Circe in the Odyssey may be identified as Galanthus, but this tenuous claim has recently been challenged.7

Galanthus’ regional folk names from England, France, Germany, and the Netherlands often refer to Candlemas or the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In Plant Lore Legends and Lyrics, Richard Folkard notes that Galanthus was once sacred to virgins and is dedicated to the Virgin Mary. He explains that because monastic tradition holds that the flowers bloom on February 2, Candlemas Day, the flower is called the Fair Maid of February, and on this day of the Purification of the Virgin Mary, her image was removed from the altar and snowdrops were placed in her absence.8 He also shares a Christian story of how Galanthus was born of snow:

An angel went to console Eve when mourning over the barren earth, when no flowers in Eden grew, and the driving snow was falling to form a pall for earth’s untimeous funeral after the fall of man; the angel, catching as he spoke a flake of falling snow, breathed on it, and bade it take a form, and bud and blow. Ere the flake reached the earth Eve smiled upon the beauteous plant, and prized it more than all the other flowers in Paradise, for the angel said to her: ’This is an earnest, Eve, to thee, that sun and summer soon shall be.’ The angel’s mission being ended, away up to heaven he flew; but where on earth he stood, a ring of Snowdrops formed a posey.9

In Romania and Moldova, Galanthus is associated with Mărţişor, an ancient tradition stretching back 8,000 years that celebrates the arrival of spring. On March 1, people present each other with Mărţişor tokens, small decorations tied with red and white string. Thought to bring fertility, beauty, and luck, while also preventing sunburns and warding off the evil eye, the Mărţişor are worn until the trees bloom and then they are hung on their twigs.10 Folktales associated with Mărţişor describe the cyclical shift from the cold dark of winter to the warm light of spring. These tales are varied and may feature the sun personified, a treacherous dragon, the spring maiden and the winter crone, or the legendary Baba Dochia. In one story, Spring is battling Winter and in their struggle Spring cuts her finger. Where her blood fell to the ground and melted the snow, a snowdrop rose up, and in this way Spring defeated Winter.

While many Galanthus folk stories have been transmitted orally, traditional knowledge of her healing properties is limited, as the classic European medical-botanical texts, herbals, and leechbooks do not mention her. Likewise, while discussing her virtues, Gerard asserts that he has “nothing to say, seeing that nothing is set downe hereof by the old writers, nor anything observed by the new,” believing that her only virtue is the beauty of her flowers.11 Yet Galanthus left breadcrumbs for modern Eastern European researchers to follow. According to anecdotal reports, in the 1950s a Bulgarian pharmacologist noticed people rubbing wild Galanthus bulbs on their foreheads to relieve nerve pain and a Russian pharmacognosist witnessed peasant women living at the base of the Caucuses treat cases of Polio in children with a decoction of Galanthus woronowii bulbs to protect against paralysis.12 Similarly in Ukraine, an ointment made of ground Galanthus bulbs and goat fat was used to treat the chronic neurological disorders radiculitis and multiple sclerosis. While in France Galanthus was instilled in the eye for cataracts and employed as an emmenagogue and an abortifacient.13

It is evident from these traditional remedies that Galanthus has an affinity for the human nervous system. This was clear to Soviet chemists who began to explore Galanthus for alkaloidal activity in the early 1950s. Alkaloids are bioactive compounds that have strong effects on the human body. Like Narcissus, Galanthus contains the alkaloid galanthamine, which has the power to cross the blood-brain barrier and today is used to slow the onset of the neurodegenerative disease Alzheimers. There is also growing evidence of a connection between galanthamine and the neurological phenomenon of lucid dreaming.14 And curiously, one of the Croatian names for Galanthus, dremuljka, links the plant to sleep, with drem relating to napping, slumbering, or nodding off.

My encounter with Galanthus this winter has left me feeling pulled to her relationship with the realm of dreams. Perhaps this isn’t surprising as I associate the time between winter and spring with the liminal, drowsiness of a waking dream. But since then, she has often been on my mind, nodding to me quietly, directing my awareness toward the dreamworlds. And while I have always had vivid dreams, their presence in my life has become a priority of late and their frequency has increased. One of the ways I like to get to know a plant is through careful observation. What is their morphology like? Where and when do they grow? How much sun and water do they need? Through this process, I thought of Galanthus waking up while most everyone else was still in their winter slumber, becoming conscious, if you will, in an unconscious time, symbolically embodying the process of lucid dreaming.

Another way I like to get to know a plant is by discerning their planetary correspondences. This is informed by the tradition of natural magic, but it is also personal as many plants we know today were not accounted for in the old magical texts. To my knowledge, this includes Galanthus. Given her affinity for the nervous system, her power to cross the blood-brain barrier, her ability to increase our conscious awareness in the realm of dreams, and even the murkiness of her historical record, I would like to offer Mercury—the trickster and psychopomp—as a planetary correspondence, or at very least, a kindred celestial spirit.

But of course, the very best way to get to know a plant is to build your own relationship. If you happen upon Galanthus, perhaps sit down on the ground next to her. Close your eyes. Rest here awhile and notice what you perceive. You can work with plants magically without touching or ingesting them, which in this case is ideal, given that all parts of Galanthus are considered toxic. For those interested in exploring how this plant can encourage lucid dreaming, you might also try an age-old method of placing a small piece of an oneiric plant beneath your pillow so that its influence can reach you while you sleep. And if you do, I wish you the sweetest of dreams.

Margaux Crump is a gardener and interdisciplinary artist exploring the entanglements between ecology, spirituality, and power. She is currently investigating the phenomena of unseen worlds, from the microscopic to the parallel mythic realms that surround us. Follow her on Instagram @margauxcrump

References

1. Guido Aschan and Hardy Pfanz. “Why Snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis L.) tepals have green marks?” Flora 201 (2006) 623 – 632. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2006.02.003

2. Trevor Dines. “What Makes Snowdrops Flowering Superstars?” BBC Earth. 2 February 2016, accessed 12 March 2025, https://web.archive.org/web/20201029180017/http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160128-what-makes-snowdrops-superstars.

3. This blog has compiled an extensive list of regional names for Galanthus: https://drawingandillusion.blogspot.com/2016/03/the-secret-history-of-snowdrops-part-ii.html

4. John Gerard. The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes. (Imprinted at London By John Norton, 1597) 120–121.

5. Freda Cox. “Galanthomania: Crazy about Snowdrops!” The Bulb Garden 10 no. 4 (2011) 1–3, 10, https://www.pacificbulbsociety.org/pbswiki/files/TBG/BG.php?v=10&n=4

6. Dioscorides Pedanius, T. A. Osbaldeston, and R. P. A. Wood, De Materia Medica: Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials: Written in Greek in the First Century of the Common Era: a New Indexed Version in Modern English (Johannesburg: IBIDIS, 2000), 519.

7. Rafael Molina-Venegas and Rodrigo Verano. “The quest for Homer’s moly: exploring the potential of an early ethnobotanical complex.” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 20 no, 11 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-024-00650-7.

8. Richard Folkard. Plant Lore, Legends, and Lyrics: Embracing the Myths, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-lore of the Plant Kingdom. (London: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1884) 546.

9. Folkard. Plant Lore. 546.

10. “Martisor – one of the most representative of Romania’s traditions.” Permanent Mission of Romania to the United Nations, accessed 12 Mar 2025, https://mpnewyork.mae.ro/en/romania-news/375#:~:text=Martisor%20a%20genuine%20Romanian%20holiday,are%20men%20who%20receive%20martisor.

11. Gerard. The Herball. 121.

12. Michael Heinrich and Hooi Lee Teoh. “Galanthamine from snowdrop—the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 92 (2004) 147 – 162, doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.012.

13. Dimitri A. Cozanitis. “The snowdrop, wellspring of galanthamine: A brief descriptive and scientific history.” Wien Med Wochenschr 171 (2021) 205 – 213, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-020-00799-2.

14. Stephen LaBerge, et al. “Pre-sleep treatment with galantamine stimulates lucid dreaming: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study.” PloS One 13, (8 Aug. 2018), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201246.

Plantings

Issue 46 – April 2025

Also in this issue:

Gardens, Greens and Reversing Alzheimer’s: A Conversation with Dr. Heather Sandison

By Liz Macklin

Growing Together

By Jake Eshelman

Breandán O Caoimh: Preserving Ireland’s Bogs– Memory, Identity, and the Path Forward

By Gayil Nalls

The Perils of Early Springtime

By Theresa Crimmins

The Language of Three Rings

By Katharine Gammon

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Pineapple Rosemary Crush Mocktail

By Gayil Nalls

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.