Deirdre Fraser: The Plant Wizard of Pearl Morissette

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Deirdre Fraser was born and raised on the shore of Lake Erie in the Niagara region of Ontario. She grew up with what she calls a ‘creator sensibility’ that was instilled in her by her parents who were artists, gardeners and plant lovers. Constantly surrounded by beautiful handmade objects such as the colorful vases that her father, a glass blower, created, she began to develop an appreciation for materials that informs her work now.

Growing up she found her mind continually preoccupied with food, plants and the land. She was fascinated with why people use or eat certain foods, which led to a deep dive into the native foods of the area she grew up in. Soon she was identifying and picking wild food from forests and fields, which lead to foraging wild food for restaurants in Toronto. She found that she had the ability to translate a lot of things she knew about the wild food of the land into tastes, smells, textures, visual beauty and stories that inspired the chefs, and that they were very keen to present them to their public. Along the way she met a young chef named Dan Hadida who had decided to open a restaurant in Niagara. Deirdre was one of the first people he invited to join him on his team for an exciting new project, a restaurant called Pearl Morissette on one of Canada’s finest winery estates.

Her part for Pearl Morissette involves helping to create the botanical foundation that the operations of the restaurant is based on. She came on a year before they opened to create a garden that would be the heart of the menu and everything else would revolve around it. Her horticulturist work involves coordinating her research and crop selection of flowers, herbs, vegetables, nuts, seeds and fruits with the chefs for menu creations. She also welcomes guests by amplifying Pearl Morissette’s ethos with fresh arrangements of food and flowers. The sensory heightened state of mind that she creates with colors, textures and new smells and tastes has earned her the official title of ‘Plant Wizard’, a name that now adorns her business cards. Her contributions have helped make the restaurant one of the most highly regarded in Canada. They use the bounty that she forages and grows in the Niagara region. Wild herbs and edible wildflowers and other delectable wild edibles are included in every dish and used in flavoring oils, powders, and pickles.

I recently spoke with Deirdre to ask about her experience with plants and translating their qualities into sensory experiences.

As Spring is here and the plant world is waking up. What plants are on your mind right now?

There’s a lot of little microclimates around Niagara, different little ecologies, and as the season changes so does the focus of my foraging. I will be foraging for edible flowers and leafy greens in the spring through summer. I grow a lot of unusual herbs in the garden and a lot of that will focus on Mediterranean style herbs that thrive because the garden is very well draining. It can be quite hot in Niagara in the summer, so those are well suited.

I also grow small fruits and berries, like tiny little strawberries the size of your pinky fingernail. Those are species that a regular farmer can’t do because it takes too much labor and they’re not as productive as modern varieties. But that’s something that I have the freedom to pursue in this setting because we focus on these more unusual ingredients that have this incredible flavor. It’s always more about the impact of the flavor on things here, so I include the berries and other fruits into the Fall.

We also do a lot of drying. I have a huge drying room set up in an old barn so that we can have different ways to preserve produce in dried form. Plants also get salted, preserved and fermented. So we have all the same ingredients all the way through the winter. We don’t order oranges from California. It’s a commitment to stay with the garden through the year just in a different form. So, it’s sort of a four-season garden, but not in the way that you would usually think.

Some of what comes out of the garden is for the floral program. The visual engagement for people that come to the property is very important. The arrangements tell them this is what it looks like right now in the garden or in the fields, but there’s no strict lines saying this is only a decorative plant, or this is only an edible plant over here.

It’s spectrum, something that’s medicinal might look spectacular, and something that looks beautiful might smell really beautiful as you’re brushing up against it or walking by. Everything has to have a kind of multisensory engagement that speaks some kind of truth about what we’re doing and about the place that we’re in. So that’s just been really, really fun for me.

Are you still foraging and what do you forage for?

Right now I’m forging a little bit less because the garden has grown and grown and then also some of the purpose of being on that site is to sort of propagate and bring in some of those things that I used to forage so they’re nearby. It takes a lot of time, but there are some things that you can’t just easily propagate, like leaves from a tree that might take 30 years to reach maturity or something. Or if it’s just easily gathered and especially abundant, then I will continue to forage that.

In Niagara, we have a lot of spice bush (lindera benzoin), it’s in the laurel family. I think it’s one of the only native plants we have in that family. It’s just the most extraordinary thing. It’s an understory plant that thrives in shade, has a beautiful gray bark with little speckles on it and beautiful form that it takes on naturally. It has very fragrant aromatic leaves, and it puts out the tiniest yellow flowers in the earliest, earliest springtime, almost late winter, and together they look like a yellow haze. Then, later in the season it produces these bright glossy fire-engine-red berries that birds like. The plant is also host for the spice bush swallow tail butterfly. It’s important to have around for all those reasons! The berries have a unique taste that the chefs are using a lot. It grows extensively throughout Niagara and it’s quite abundant here, so I’m not concerned about over harvesting. I always pick very carefully anyways.

We have used the fresh berries various ways like infused and so on. Dried whole berries are crushed up and used. The twigs are used to flavor things. In the bakery cafe last year, they made this beautiful little brioche bun flavored with the berries. Instead of using cinnamon or one of the typical spices brought in from far away, they were using spice bush instead and some other herbs to give you this interesting warm spiciness. I think it translated really beautifully.

We do a tasting menu that changes on a weekly basis. Every week I send them a list of exactly what is in season, how ripe it is, and the moment that something is at its perfection. There’s also a farmer on site growing phenomenal vegetables who does the same thing. The produce may go directly on the menu for that week, or it may need to be preserved for much later. So, there might be a case where I gave them spice bush in the late Fall, and they will be dried for a dish made in late February.

Right now, chefs have this really spectacular cultural power to translate new ideas, new ingredients, or forms, or thoughts to the public. People really pay attention to restaurant culture and look to chefs to do that. They translate the sensory experience of plants in a way that I couldn’t do on my own.

Aromatic plants and herbs, particularly the native ones, can engage people with a tangible experience. People are interested in things that heighten the senses and benefit them. For a lot of people, getting a little bit closer and smelling things and tasting them can engage them and get them interested in a plant in a way that they wouldn’t be otherwise. Maybe people would be a little bit more interested in milkweed, not just because it’s for butterflies, but because it supplies some beautiful edible products as well. You have to work within that. People have a self-interest and I think that that’s not necessarily a bad thing sometimes.

At what point when you are foraging or growing are plants in their full dimension and can energize our lives?

When you are foraging, it’s a matter of paying close attention. The vintner, Francois, is very keyed into the grapes. He explained that you need to develop eyes on the ends of your fingers so you get very sensitive to touch. You also get very sensitive to smell and taste as well. I’m constantly nibbling on things to see how they are, because it may be that a dandelion was tasting really good one week, and then you had a bout of no rain and sun, and it suddenly twists in a couple of days and it’s a bit too bitter. The taste can change fairly quickly.

If you can engage all those senses, then they start to work in a different way than you expected. I found that a couple of years into foraging, I was getting to a point where I’d be driving down a country road with the windows down and I could tell there was a patch of wild roses about 500 feet ahead of me because I could smell it coming through the window. It feels like something extra sensory, when all your senses come into one place and start getting used more often. That’s what we achieve with the garden and the restaurant, is engaging guests to come into closer awareness with their senses. It’s very hard to just verbally describe a garden and its value unless you can really get in there and start rubbing things and get people’s faces in it.

I read that you were inspired by Euell Gibbons and his 1962 book, Stalking the Wild Asparagus. I must admit, he was one of my early heroes also. Complete fascination, and never saw the world outside my house the same after that. I think it’s fascinating that the world around us is, for the large part, edible.

Absolutely. I think that book affected a lot of people. I know my parents had read it, they hadn’t gone wild for foraging, but they did some, and I knew you could eat cattails and some other things. I read it again later and thought his chapter on picking wild strawberries could be considered an influential piece of nature writing. It’s very well done. It’s about how there’s value beyond getting food easily, there was this sensory quality from the wild strawberry that you couldn’t get anywhere else and there was an enjoyment in spending the time getting them. I really resonated with that, because I’ve spent a lot of time on my hands and knees picking wild strawberries.

I think people don’t realize that food is all around them. And even if you’re in cities, it’s growing in vacant lots and on the roadside and small backyards. I think we can open people’s eyes again to the idea that life is basically an edible adventure.

Do you have friends that you’ve influenced with your foraging who have incorporated it into their lives?

I’ve got a great friend who’s an artist who’s Ukrainian, who actually influenced me! I’ll never be as good of a forager as she is naturally because of their culture. In Ukraine, everybody forages close to home regularly as a matter of enjoyment. It’s something families go out and do together on a weekend. I hope that I’ve had some small influence on the restaurant community in Toronto.

When I was foraging regularly, I was trying to encourage more chefs to do that. There’s always, unfortunately, very strict hierarchies in restaurants, but I hope young chefs see the stuff coming through from foraging. By handling it a lot and seeing and recognizing it perhaps on their days off they will be inspired to check things out near them and see what the possibilities are. It is just changing your eye so as you look around, the landscape shifts. Suddenly, you know a few things and you can read it. It’s like a book, with all these plants in relation to each other. It’s a form of literacy.

Do you bring any wild plants into the garden?

I have. For instance, there’s a tiny little wild ground cherry called Physalis, in the nightshade family. I’ve found it listed in the prior Canada, Ontario, noxious weeds publication because it spreads quite a lot. But it’s beautiful. I found it growing right along the Lake Erie shore. It was in certain parts that make me think it had been in that area for a long time. It is ripe extremely late in the season. October is when they finally drop off the plant and rest on the ground, ready to be picked up.

It has the most amazing taste. The species that you would get in the supermarket is a very different species, and I think it’s probably also picked under-ripe. The wild one is so much better. It’s just delicious!

Furthermore, I’m glad that I propagated it. If I hadn’t thought it was valuable, then it might be gone because the spot by the lake where I found it has since been bulldozed. There’s a lot of growth in Niagara, a lot of people moving in outside of Toronto, which creates a sort of pressure to protect these plants. That’s been another reason to focus on the garden as well.

So are you a seed saver?

I know that by saving seeds, every single time you save a seed, you’re helping to adapt that seed to your climate. I’m saving the seeds of the annual flowers that I grow. Aside from that, a lot of what I have in the garden is perennial herbs. So those ones come back every year, and they’re usually a lot of the more flavorful herbs. They come up quite early in the spring, so they fill in what they call the hunger gap here. The hunger gap is the moment where as soon as it gets warm, people want spring food, but it takes longer than everyone thinks. So some of the more famous or favorite spring foods, like rhubarb or asparagus are perennials because they can tolerate some cold, and they can come up quite early in the season. Whereas the annual vegetables, aside from maybe some peas and radishes, they do take a little bit longer. Even here, the peas won’t be ready in our climate until about June unless you have them undercover.

Why is it important that people are engaged with their senses?

There’s a certain time that my mom talks about when she was growing up in Winnipeg, when the cottonwoods would have this sweet, beautiful smell, which was just in the air. Maybe there are more people that remember and enjoy this smell, but it can also be lost if nobody particularly points it out or knows what plant it’s coming from. It’s easy to lose the natural knowledge of that. So, it’s important to discuss those kinds of scents and scent memories and their plant origins because that is part of our cultural heritage. It’s so important that people are engaged with their senses and with the aromatic compounds of the natural world.

Be sure to read Deirdre Fraser’s personal recipe for Cucumber and Sour Cherry Salad, also in this issue.

Deirdre Fraser is a gardener, forager, florist and is known as the Plant Wizard for Pearl Morissette, a restaurant at one of Canada’s finest winery estates. Located in the town of Jordan Station, in Niagara, Ontario. Pearl Morissette is known for their unique wines and inspired menu, which is a take on modern French and created by co-chefs Daniel Hadida and Eric Robertson.

Deidre is on Instagram @vibrant_matter, and the restaurant can be found at @restaurant_pearlmorissette or online at www.pearlmorissette.com.

Plantings

The Real Magic Kingdom: Florida’s Corkscrew Swamp

By Gayil Nalls

Mind the Darién Gap: Saving Central America’s Endangered Rainforest

By Alexandra Climent

Your Legacy on Earth May Be a Plant

By Veronique Greenwood

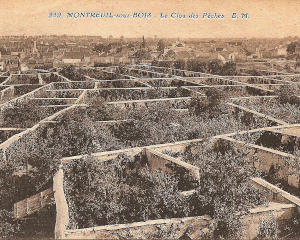

Fruit Walls: Urban Farming in the 1600’s

By Kris De Decker

The Goddess & The Rose

By Nuri McBride

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Cucumber and Sour Cherry Salad

By Deirdre Fraser

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.