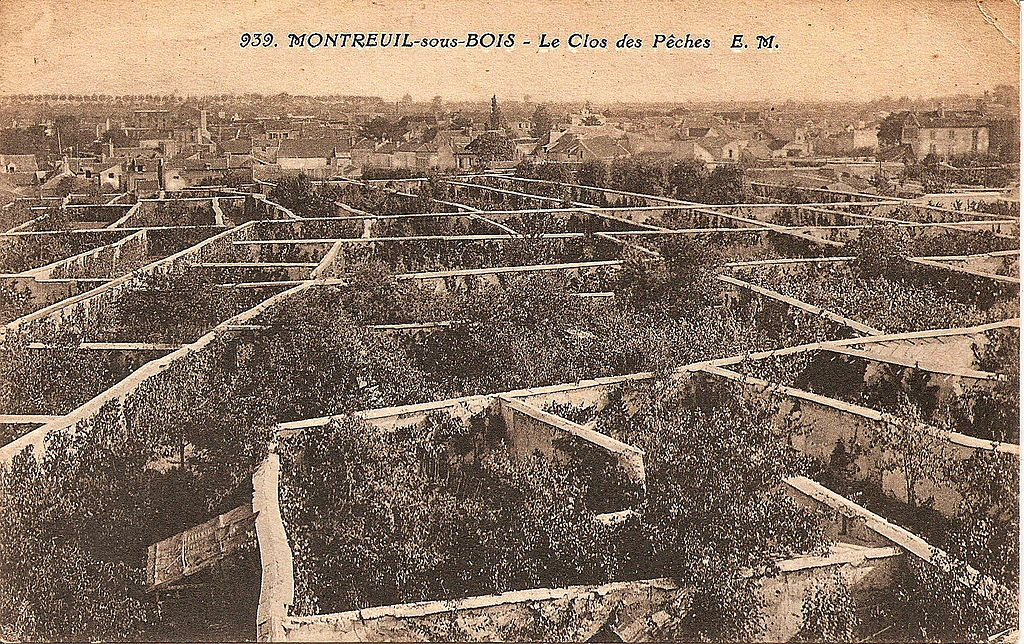

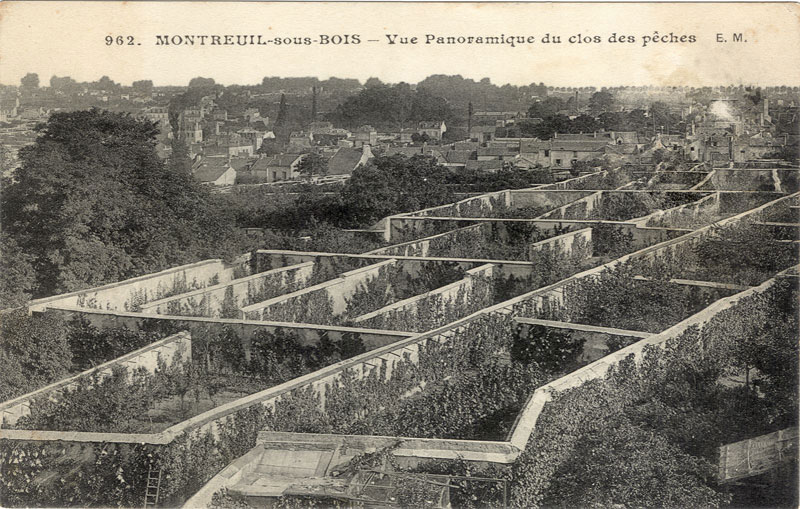

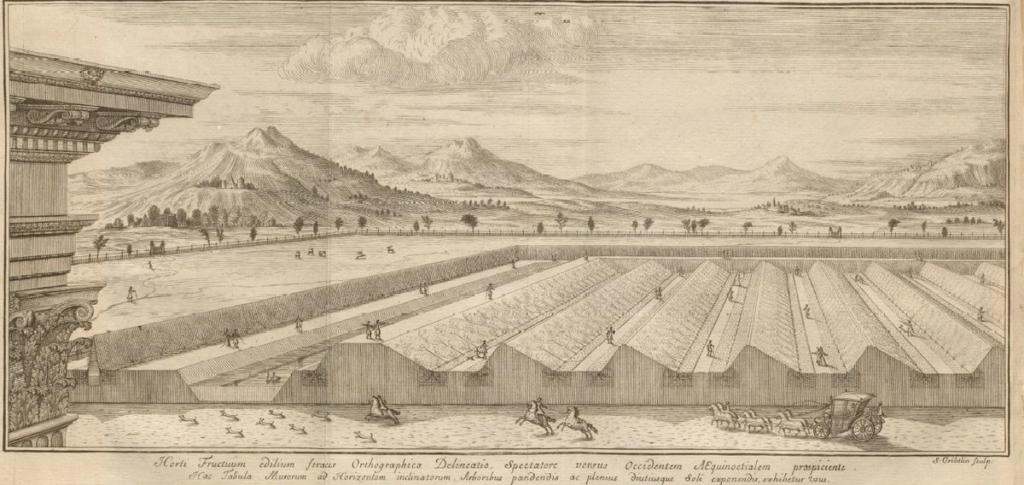

Fruit walls in Montreuil, a suburb of Paris.

Fruit Walls: Urban Farming in the 1600’s

By Kris De Decker

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

We are being told to eat local and seasonal food, either because other crops have been transported over long distances, or because they are grown in energy-intensive greenhouses. But it wasn’t always like that. From the sixteenth to the twentieth century, urban farmers grew Mediterranean fruits and vegetables as far north as England and the Netherlands, using only renewable energy.

These crops were grown surrounded by massive “fruit walls”, which stored the heat from the sun and released it at night, creating a microclimate that could increase the temperature by more than 10°C (18°F). Later, greenhouses built against the fruit walls further improved yields from solar energy alone.

It was only at the very end of the nineteenth century that the greenhouse turned into a fully glazed and artificially heated building where heat is lost almost instantaneously — the complete opposite of the technology it evolved from.

The modern glass greenhouse, often located in temperate climates where winters can be cold, requires massive inputs of energy, mainly for heating but also for artificial lighting and humidity control.

According to the FAO, crops grown in heated greenhouses have energy intensity demands around 10 to 20 times those of the same crops grown in open fields. A heated greenhouse requires around 40 megajoule of energy to grow one kilogram of fresh produce, such as tomatoes and peppers. [source – page 15] This makes greenhouse-grown crops as energy-intensive as pork meat (40-45 MJ/kg in the USA). [source]

In the Netherlands, which is the world’s largest producer of glasshouse grown crops, some 10,500 hectares of greenhouses used 120 petajoules (PJ) of natural gas in 2013 — that’s about half the amount of fossil fuels used by all Dutch passenger cars. [source: 1/2]

The high energy use is hardly surprising. Heating a building that’s entirely made of glass is very energy-intensive, because glass has a very limited insulation value. Each metre square of glass, even if it’s triple glazed, loses ten times as much heat as a wall.

Fruit Walls

The design of the modern greenhouse is strikingly different from its origins in the middle ages [*]. Initially, the quest to produce warm-loving crops in temperate regions (and to extend the growing season of local crops) didn’t involve any glass at all. In 1561, Swiss botanist Conrad Gessner described the effect of sun-heated walls on the ripening of figs and currants, which mature faster than when they are planted further from the wall.

Gessner’s observation led to the emergence of the “fruit wall” in Northwestern Europe. By planting fruit trees close to a specially built wall with high thermal mass and southern exposure, a microclimate is created that allows the cultivation of Mediterranean fruits in temperate climates, such as those of Northern France, England, Belgium and the Netherlands.

The fruit wall reflects sunlight during the day, improving growing conditions. It also absorbs solar heat, which is slowly released during the night, preventing frost damage. Consequently, a warmer microclimate is created on the southern side of the wall for 24 hours per day.

Fruit walls also protect crops from cold, northern winds. Protruding roof tiles or wooden canopies often shielded the fruit trees from rain, hail and bird droppings. Sometimes, mats could be suspended from the walls in case of bad weather.

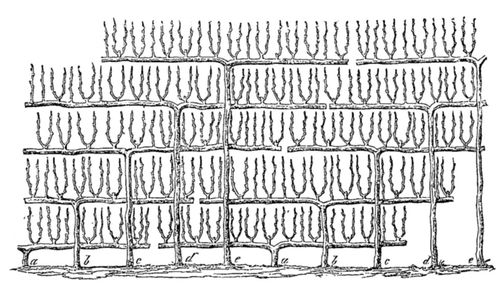

The fruit wall appears around the start of the so-called Little Ice Age, a period of exceptional cold in Europe that lasted from about 1550 to 1850. The French quickly started to refine the technology by pruning the branches of fruit trees in such ways that they could be attached to a wooden frame on the wall.

This practice, which is known as “espalier”, allowed them to optimize the use of available space and to further improve upon the growth conditions. The fruit trees were placed some distance from the wall to give sufficient space for the roots underground and to provide for good air ciculation and pest control above ground.

Peach Walls in Paris

Initially, fruit walls appeared in the gardens of the rich and powerful, such as in the palace of Versailles. However, some French regions later developed an urban farming industry based on fruit walls. The most spectacular example was Montreuil, a suburb of Paris, where peaches were grown on a massive scale.

Established during the seventeenth century, Montreuil had more than 600 km fruit walls in the 1870s, when the industry reached its peak. The 300 hectare maze of jumbled up walls was so confusing for outsiders that the Prussian army went around Montreuil during the siege of Paris in 1870.

Peaches are native to France’s Mediterranean regions, but Montreuil produced up to 17 million fruits per year, renowned for their quality. Building many fruit walls close to each other further boosted the effectiveness of the technology, because more heat was trapped and wind was kept out almost completely. Within the walled orchards, temperatures were typically 8 to 12°C (14-22°F) higher than outside.

The 2.5 to 3 metre high walls were more than half a metre thick and coated in limestone plaster. Mats could be pulled down to insulate the fruits on very cold nights. In the central part of the gardens, crops were grown that tolerated lower temperatures, such as apples, pears, raspberries, vegetables and flowers.

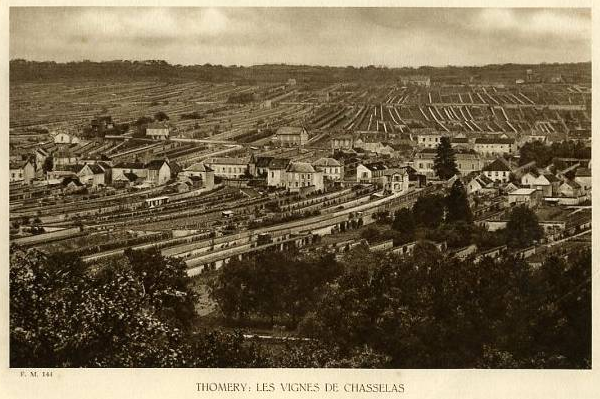

Grapes in Thomery

In 1730, a similar industry was set up for the cultivation of grapes in Thomery, which lies some 60 km south-east from Paris — a very northern area to grow these fruits. At the production peak in the early twentieth century, more than 800 tonnes of grapes were produced on some 300 km of fruit walls, packed together on 150 hectares of land.

The walls, built of clay with a cap of thatch, were 3 metres high and up to 100 metres long, spaced apart 9 to 10 metres. They were all finished by tile copings and some had a small glass canopy.

Because vines demand a dry and warm climate, most fruit walls had a southeastern exposure. A southern exposure would have been the warmest, but in that case the vines would have been exposed to the damp winds and rains coming from the southwest. The western and southwestern walls were used to produce grapes from lower qualities.

Some cultivators in Thomery also constructed “counter-espaliers”, which were lesser walls opposite the principal fruit walls. These were only 1 metre high and were placed about 1 to 2.5 metres from the fruit wall, further improving the microclimate. In the 1840s, Thomery became known for its advanced techniques to prune the grape vines and attach them to the walls. The craft spread to Montreuil and to other countries.

The cultivators of Thomery also developed a remarkable storage system for grapes. The stem was submerged in water-filled bottles, which were stored in large wooden racks in basements or attics of buildings. Some of these storage places had up to 40,000 bottles each holding one or two bunches of grapes. The storage system allowed the grapes to remain fresh for up to six months.

Serpentine Fruit Walls

Fruit wall industries in the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) were also aimed at producing grapes. From the 1850s onwards, Hoeilaart (nearby Brussels) and the Westland (the region which is now Holland’s largest glasshouse industry) became important producers of table grapes. By 1881, the Westland had 178 km of fruit walls.

The Dutch also contributed to the development of the fruit wall. They started building fruit walls already during the first half of the eighteenth century, initially only in gardens of castles and country houses. Many of these had unique forms. Most remarkable was the serpentine or “crinkle crankle” wall.

Although it’s actually longer than a linear wall, a serpentine wall economizes on materials because the wall can be made strong enough with just one brick thin. The alternate convex and concave curves in the wall provide stability and help to resist lateral forces. Furthermore, the slopes give a warmer microclimate than a flat wall. This was obviously important for the Dutch, who are almost 400 km north of Paris.

Variants of the serpentine wall had recessed and protruding parts with more angular forms. Few of these seem to have been built outside the Netherlands, with the exception of those erected by the Dutch in the eastern parts of England (two thirds of them in Suffolk county). In their own country, the Dutch built fruit walls as high up north as Groningen (53°N).

Another variation on the linear fruit wall was the sloped wall. It was designed by Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, and described in his 1699 book “Fruit Walls Improved”. A wall built at an incline of 45 degrees from the northerm horizon and facing south absorbs the sun’s energy for a longer part of the day, increasing plant growth.

Heated Fruit Walls

In Britain, no large-scale urban farming industries appeared, but the fruit wall became a standard feature of the country house garden from the 1600’s onwards. The English developed heated fruit walls in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to ensure that the fruits were not killed by frost and to assist in ripening fruit and maturing wood.

In these “hot walls”, horizontal flues were running to and fro, opening into chimneys on top of the wall. Initially, the hollow walls were heated by fires lit inside, or by small furnaces located at the back of the wall. During the second half of the nineteenth century, more and more heated fruit walls were warmed by hot water pipes.

The decline of the European fruit wall started in the late nineteenth century. Maintaining a fruit wall was a labour-intensive work that required a lot of craftsmanship in pruning, thinning, removing leaves, etcetera. The extension of the railways favoured the import of produce from the south, which was less labour-intensive and thus cheaper to produce. Artificially heated glasshouses could also produce similar or larger yields with much less skilled labour involved.

The Birth of the Greenhouse

Large transparant glass plates were hard to come by during the Middle Ages and early modern period, which limited the use of the greenhouse effect for growing crops. Window panes were usually made of hand-blown plate glass, which could only be produced in small dimensions. To make a large glass plate, the small pieces were combined by placing them in rods or glazing bars.

Nevertheless, European growers made use of small-scale greenhouse methods since the early 1600’s. The simplest forms of greenhouses were the “cloche”, a bell-shaped jar or bottomless glass jug that was placed on top of the plants, and the cold- or hotframe, a small seedbed enclosed in a glass-topped box. In the hotframe, decomposing horse manure was added for additional heating.

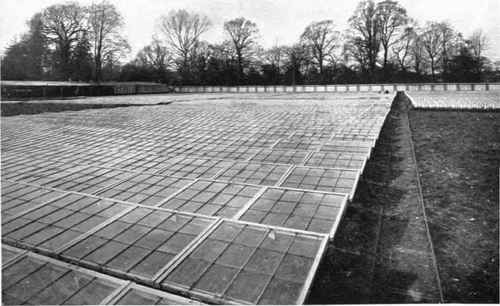

In the 1800s, some Belgian and Dutch cultivators started experimenting with the placement of glass plates against fruit walls, and discovered that this could further boost crop growth. This method gradually developed into the greenhouse, built against a fruit wall. In the Dutch Westland region, the first of these greenhouses were built around 1850. By 1881, some 22 km of the 178 km of fruit walls in the westland was under glass.

These greenhouse structures became larger and more sophisticated over time, but they all kept benefitting from the thermal mass of the fruit wall, which stored heat from the sun for use at night. In addition, many of these structures were provided with insulating mats that could be rolled out over the glass cover at night or during cold, cloudy weather. In short, the early greenhouse was a passive solar building.

The first all glass greenhouses were built only in the 1890s, first in Belgium, and shortly afterwards in the Netherlands. Two trends played into the hands of the fully glazed greenhouse. The first was the invention of the plate glass production method, which made larger window panes much more affordable. The second was the advance of fossil fuels, which made it possible to keep a glass building warm in spite of the large heat losses.

Consequently, at the start of the twentieth century, the greenhouse became a structure without thermal mass. The fruit wall that had started it all, was now gone.

During the oil crises of the 1970s, there was a renewed interest in the passive solar greenhouse. However, the attention quickly faded when energy prices came down, and the fully glazed greenhouse remained the horticultural workhorse of the Northwestern world. The Chinese, however, built 800,000 hectare of passive solar greenhouses during the last three decades — that’s 80 times the surface area of all glass greenhouses in the Netherlands. We discuss the Chinese greenhouse in the second part of this article.

This article previously appeared in Low-Tech Magazine.

Plantings

The Real Magic Kingdom: Florida’s Corkscrew Swamp

By Gayil Nalls

Mind the Darién Gap: Saving Central America’s Endangered Rainforest

By Alexandra Climent

Your Legacy on Earth May Be a Plant

By Veronique Greenwood

The Goddess & The Rose

By Nuri McBride

Deirdre Fraser: The Plant Wizard of Pearl Morissette

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Cucumber and Sour Cherry Salad

By Deirdre Fraser

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.