The Artichoke Blossom, an Exploding Castle

By Sam Stoeltje

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

In June, I crossed the Atlantic with my partner for a much-needed vacation. A leg of the trip brought us to Avignon, in southern France, where in the fourteenth century, due to the fluctuations of religious and political strife, the seat of the papacy, undertook a brief exile. The medieval city is organized around the stark, towering Palais des Papes, essentially a castle, which has the vast stone walls of a Game of Thrones set piece. Visitors to the Palais are given a tablet which, carried from room to room, filters the severe chambers, with their faded tapestries and accumulated centuries of scratchiti, through a digital time machine. A dark, cavernous fireplace fills with computer-generated flames, and suddenly you are a guest in the palace kitchen, or at least, this is the intention. If the augmented reality was underwhelming, the pontifical garden were not. It revealed itself beyond the battlements and chambers. The Palais des Papes has an official website, which narrates the creation of the garden as follows:

Bishop of Avignon in 1310, Jacques Duèse became Pope John XXII in 1316 and settled in Avignon. He annexed the neighboring buildings of the episcopal palace, and had the adjacent stables rebuilt. An orchard was redeveloped in 1324: the ground was leveled, trees and lawns were planted, a watering system was put in place, a wall was built to close off the area. The foundations of the pontifical gardens [were] laid.

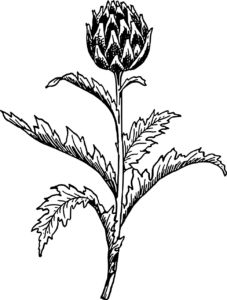

What I remember most about the walled garden was my first encounter with an artichoke blossom. The size of a human hand, it was a purple explosion, gorgeous and slightly frightening, the kind of organism (like a vampire squid or a banyan tree) that stretches the human formal imagination merely by existing.

In the months since my return, I kept thinking about these blossoms, the garden, and the palace walls that concealed them. The common globe artichoke is a cultivar of its parent, the wild cardoon (Cynara cardunculus), with “cardoon” referring both to this ancestor as well as, more commonly, to the leafy cardoon. This separate cultivar yields an edible stalk and leaves. The artichoke, on the other hand, was selectively bred through the Middle Ages to produce the familiar “heart,” nestled within its own palatial series of semi-edible, discretely thorned leaves. If it isn’t apparent yet, the more I thought about the artichoke, the more it came to resemble the pontifical garden in which I encountered it.

Is this a coincidence, a metaphor? The centuries-long selective breeding of the globe artichoke has been obscured over time but may have begun around the turn of the first millennium in Rome, spreading throughout the Mediterranean from there.1 Over the next five hundred or so years, in addition to selecting for the gigantism of the head (or “heart”) of the plant, Medieval gardeners produced specimens with more, bigger, and tougher leaves. The effect was that the artichoke increasingly resembled a fortress protecting its own Edenic pleasure garden, the rich and savory heart, just as the battlements of the Palais guarded the putatively holy workings of the Papacy, not only the political and liturgical wranglings but the intellectual pursuits of church functionaries with ample downtime.

One of these pursuits was the cultivation of a philosophy eventually described as “humanism,” which sometimes resembles an ink blot more than a coherent philosophical movement. Is humanism a rejection of theology, a return to “the classics”? Is it an embrace of science, empiricism, and positivism, those means by which humans observe and measure the real, or is it a turn inward, a reliance upon the reasoning intellect? Foundationally, the major humanists display a deep commitment to reason and the rational. But given that proto-racist prejudices condemned vast populations of humans as incapable of reason, “humanism” perversely enjoyed its ascendance at the same time as the dual moral disasters of colonization and the slave trade.2

Rene Descartes, arch-rationalist, is often identified as the premier philosophical author of this solipsistic, perhaps narcissistic movement “inward,” but antecedents have been found in, for example, the ecstatic Spanish nun Teresa of Avila, whose Interior Castle conceived of meditative practice as a journey to the center of a castle.3 Earlier still, and in the city of Avignon no less, Petrarch arrived at a humanistic ethos through his engagement with Greek and Roman philosophy and literature. Petrarch worked for the church for many years, and likely passed through the walls of the Palais while developing his thoughts on the relation between self and world. Did he pass by the pontifical gardens? Did he smell the flowers?

In remembering, and meditating over, the artichoke blossom in the garden of the Palais des Papes, I have found myself building associations: artichoke, walled garden, castle, humanism, and meditation itself in certain iterations. Returning to my earlier question, I wonder if this is the human practice of metaphor-working, or whether these are all effects of a common, culturally specific, formal, and imaginary movement. It would be a medieval-feudal tendency to build castles, to protect the self through rigid battlements, and to value it above human and non-human and more-than-human others.

To speculate whether this manifests in the form of the artichoke only appears ridiculous if we do not recall that generations of selective breeding for traits desirable to humans is an ongoing practice and that humans are co-authors in the collaboration with organisms across centuries.

When I approached the artichoke blossom to look at it more closely, I noticed bees working their blissful way through the forest of the bloom for nectar and pollen.

The artichoke, to bloom, must explode beyond the walls of its own castle, in the process withholding its heart from at least one form of human enjoyment (I like mine with lemon, garlic, and olive oil). This is just a different aesthetic, a movement away from a selectively bred gustatory reward, and toward a more ancestral, non-modern beauty, a beauty that is also alien, even slightly frightening.

I am wondering now about the self, a “humanist” concept of the self as worthy of privilege and priority above and beyond the non-self, the abundant other, which we carry with us, along with perhaps a more innate and stubborn tendency to build castles—in the sky, but also everywhere else—and what it might mean to bloom away, outward, beyond. The artichoke blossom exceeds human design and desire, exploding its own battlements and thereby entering the symbiogenetic fray of interspecies collaboration. Perhaps in the blossoming of the artichoke I perceived, surprisingly enough, a revolutionary politics, one that foregoes the (always-classed, always-racialized) hierarchy of human privilege in favor of relationships of mutual care and, one might hope, healing.

Sam Stoeltje, PhD, is a professor at Utica University. He/They specialize in Religious Studies, Critical and Decolonial Theory, and Epistemic Justice.

1Gabriella Sonnante, Domenico Pignone, Karl Hammer. “The Domestication of Artichoke and Cardoon: From Roman Times to the Genomic Age.” Annals of Botany 100: 5 (2007).

2Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3.3 (Fall 2003).

3Christia Mercer, “Descartes’ Debt to Teresa of Ávila, or Why We Should Work on Women in the History of Philosophy,” Philosophical Studies, vol. 174, no. 10, 2017.

Plantings

Nature as Model and Mentor: Biomimicry and Ecosystem Restoration

By Gayil Nalls

Ingraining ‘Nature’ into ‘Human Nature’

By Shreya Bhagwat

The Very Hungry Caterpillar and the Ecosystem

By Katharine Gammon

Fostering a Deeper Connection with Plants in the UK

By Katherine Moore

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Aussie Energy Balls

By Maria Rodale

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.