Indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) flowers and leaves. Pancrat, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Exploring the Vibrant World of Indigo: History, Controversies, and Sustainable Solutions

By Karen Bauer

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Colors influence our feelings, moods and even behaviors. They also play an integral part in our everyday lives, from the clothes we wear, the textiles we use, the food we eat, to the art we enjoy, yet we rarely consider where the vibrant hues come from or their impacts on the environment, labor, and human health. One color that encapsulates this intricate relationship and completely captivates humans is indigo. In its purest form, this color can only be found in nature by processing the leaves of the indigo plant species, but throughout history humans have produce it synthetically for mass consumption with destructive impacts on human health and the environment. By exploring its complex history and legacies and its far-reaching impacts on our world today, we can enrich our understanding of the world around us, and make more informed choices about the products we consume so that we can reap the benefits of this vibrant color sustainably and never have to live in a world without indigo.

“The creation of a colour as magical as Indigo is a work of love; all consuming, the process from cultivating the plant to extracting pigments can take over two years and is an intrinsic part of so many lives…” -Kerry Flint

Mystical Indigo

Indigo, most commonly associated with blue jeans, and one of the most beautiful blues available to artists, has a long and fascinating history that many are unaware of. One of the most recognized plant pigments, it comes from a family of plants found across the globe, each region of the world having its own species; true indigo or Indigofera tinctoria is the most widely known, and Polygonum tinctorium is known as Japanese indigo. The plant’s leaves are dark green, and the mystical blue color is unveiled through a fermentation process. When a dyed article is exposed to the air, the color transition occurs, starting from yellow to green, and ultimately resulting in the well-known indigo shade. Each region developed unique techniques to extract the indigo dye, along with specific approaches of applying it to enhance art, clothing, textiles, and ceremonial items, allowing them to convey the distinct culture and beliefs of each area.

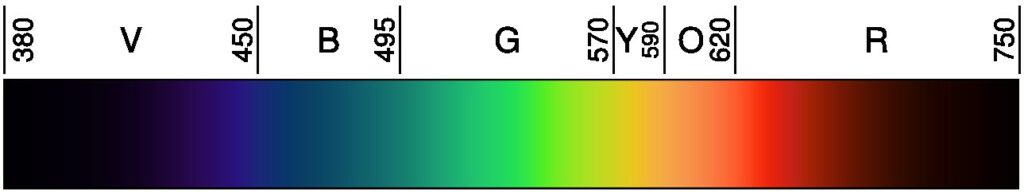

Unraveling the Color Spectrum

Indigo’s place in the color spectrum has been a subject of debate and some modern rainbows, such as those found on the gay pride flag or Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album cover, only feature six colors, omitting indigo altogether. Some argue that indigo should be classified as a variation of blue or purple due to its proximity to these colors in the wavelength spectrum (420-450 nanometers). So why was it even names as a color? The inclusion of indigo in the rainbow owes its origin to mathematical and musical connections, with Sir Isaac Newton expanding the spectrum to seven colors to align with Pythagoras’ beliefs. Pythagoras noticed patterns: he observed that seven was a magical number that somehow connected disparate phenomena; seven musical notes, seven planets (at that time), seven days of the week…Newton believed in Pythagorean. When Newton started his experiments with color (1666-1672), he originally only subdivided the spectrum into five colors (red, yellow, green, blue and purple), but revised the number to seven, adding orange and indigo, because Pythagoras believed that there was a connection between color and music. And there are seven natural notes, so there should also be seven principal colors.

Indigo Timeline

Indigo Timeline

Indigo’s Troubled Past

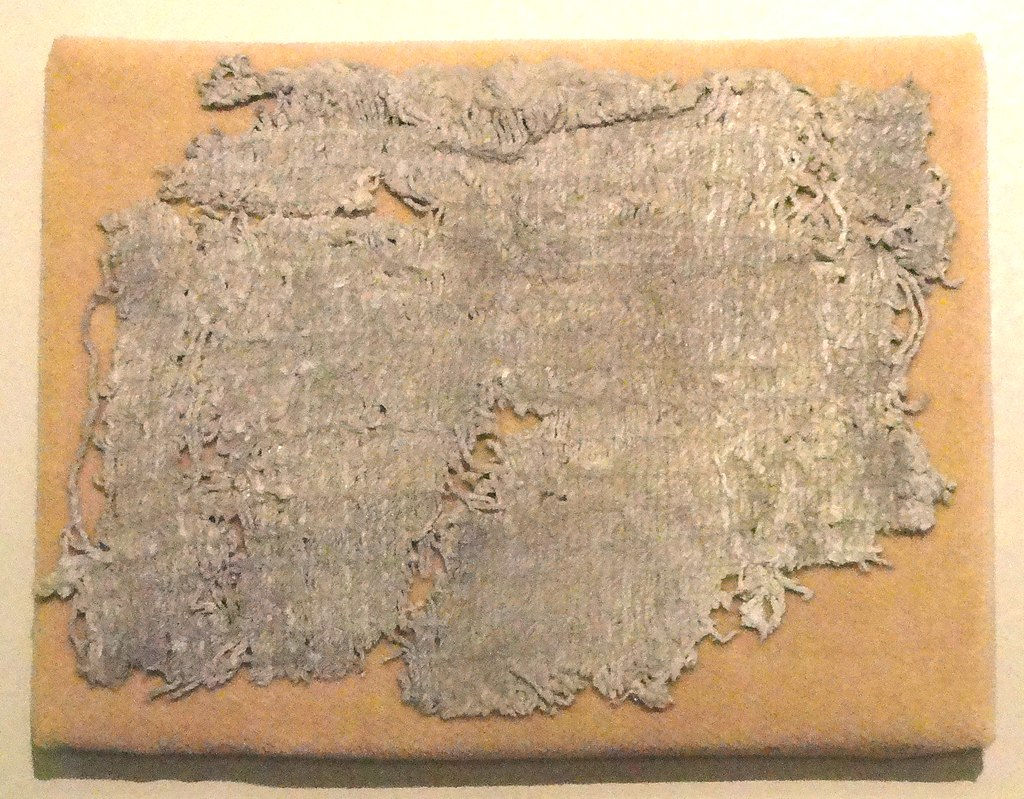

Indigo’s history intertwines with the dark legacies of the slave trade, colonialism, and exploitation. In 2007, small cotton scraps were discovered on an excavation of Huaca Prieta (Peru), pointing to Peru as the place where humans first learned to dye fabrics with indigo around 4000 BC.1 Prior to this discovery, the oldest known dyed fabrics were Egyptian textiles with indigo-dyed bands from the Fifth Dynasty, roughly 2400 BC. The earliest known examples of indigo in the Americas, however, are just 2,500 years old.

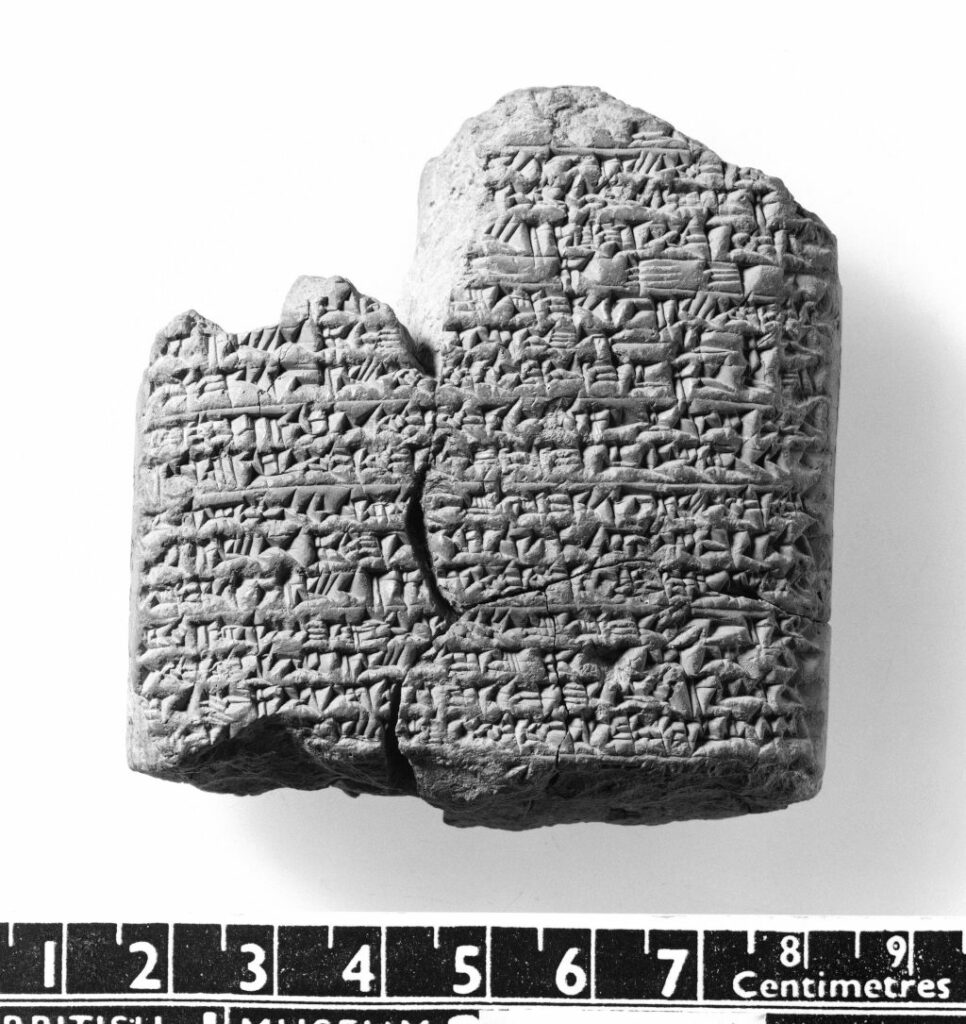

India was the main source of indigo where their knowledge of how to process indigo into hard cakes, which some thought was a mineral, was a closely guarded secret. Known as “blue gold”, it was traded along with tea, coffee, silks, and spices along the Silk Road. The first ever non-violent revolt occurred when indigo farmers from across the country came together to fight for better treatment. China and Japan and the ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Britain, Peru, Iran, and Africa had knowledge about the dye as well. Once Europe started growing indigo in its colonies, production here dwindled. However, after synthetic indigo was developed, plant-based indigo cultivation in India started again and is still strong today.

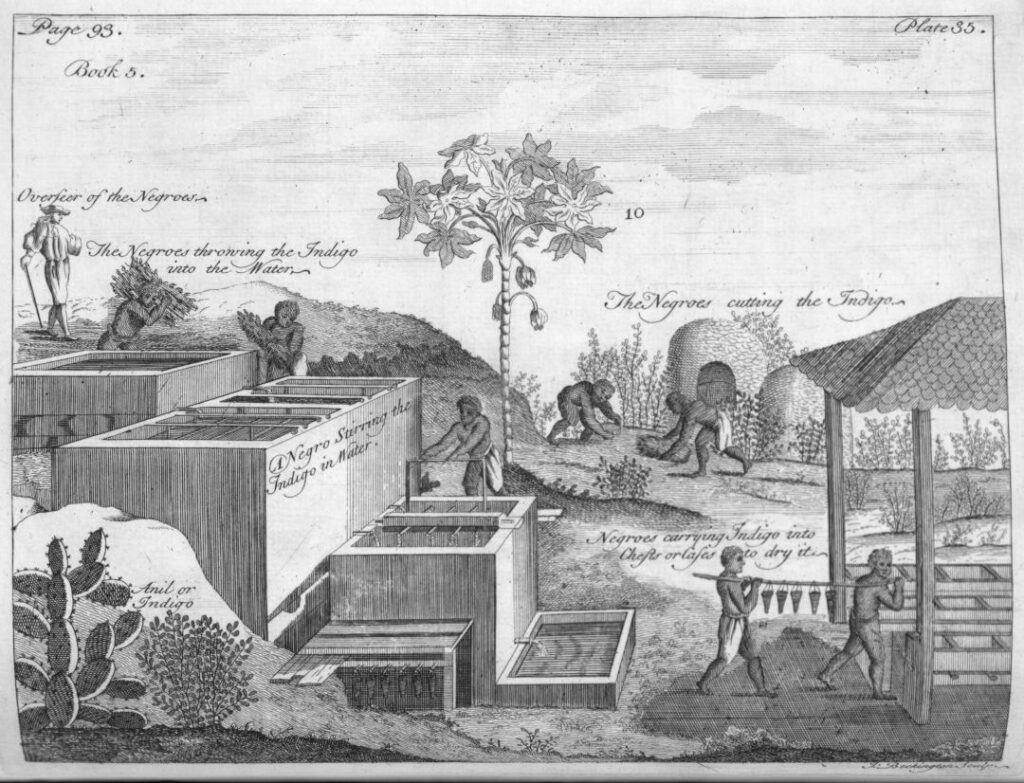

Indigo became an important trade commodity because it was the only natural material that imparted a vibrant blue, a symbol of status and power for the elite, especially seen in the clothing they wore. European powers created plantations in their colonies just to cultivate it for export, and used enslaved labor and fueled the exploitation of people from India, West Africa and the Americas because they had the expertise and had been growing and processing it for centuries. In 1739, Eliza Lucas was put in charge of the family’s plantations in rural South Carolina. Hearing the French would pay for indigo dye, Eliza learned the thousand-year-old secret process of making indigo dye from slaves, and in return she taught them to read. Indigo dye went on to become one of South Carolina’s largest exports and laid the foundation for the incredible wealth of South Carolina and even helped fund the American Revolution War. The process of producing indigo was grueling and dangerous, and many enslaved people suffered and died as a result of their labor. Donna Hardy, the president and founder of the International Center for Indigo Culture says:

…when prices were high, indigo dyestuff could be exchanged for slaves; it is said that a planter in South Carolina could fill his bags with indigo and ride to Charleston to buy a slave with the contents, “exchanging indigo pound for pound of Negro weighed naked.”

https://laits.utexas.edu/cairo/files/ExplorersTradersImmigrantsFull.pdf

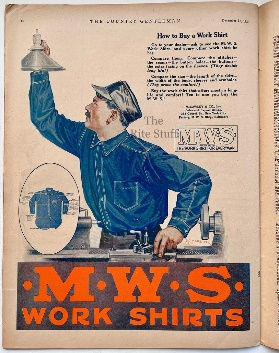

“Slavery wasn’t even legal in Georgia until indigo became the main export in South Carolina, the [British] governors in Georgia decided to legalize slavery to keep the indigo industry going.” Slaves in Saint Domingue (Haiti), lead a revolt and became the first country to abolish slavery.2 Unfortunately, slave labor is still a part of the indigo story today, especially in the garment industry. In 1865, (toxic) synthetic indigo dyes were created using petrochemicals by German Adolf von Baeyer, and this made cultivating indigo less profitable, so the industry declined significantly. In 1873, Levi Strauss patented blue jeans, made with indigo from the West Indies. Indigo is now more associated with the working class, and chambray shirts (also made with indigo) that workers wore are the origins of the phrase “blue-collar workers”.

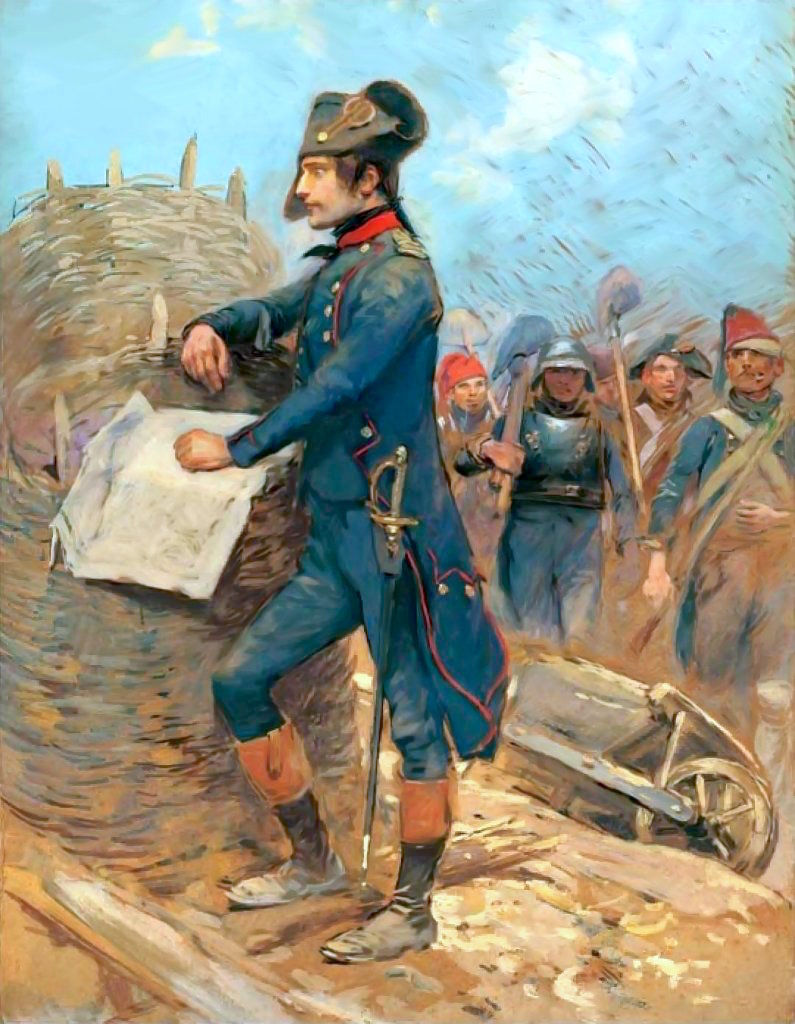

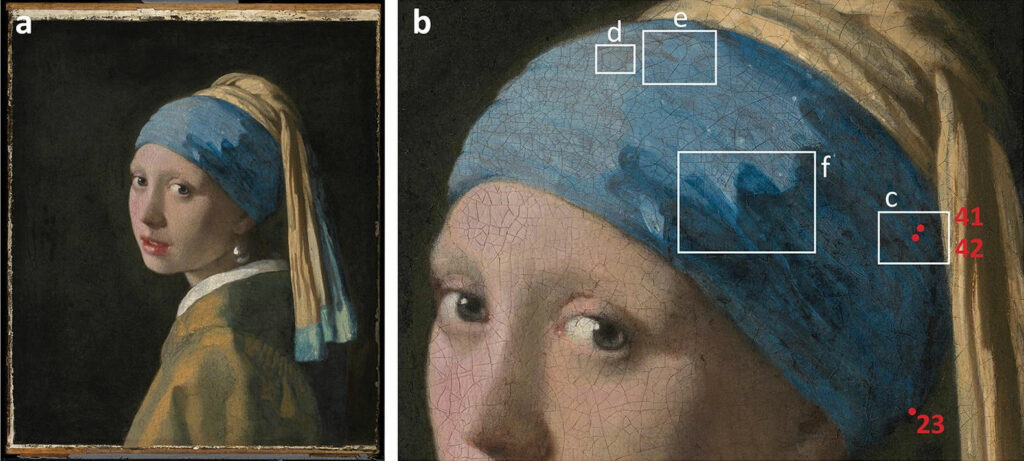

These images tell the story of indigo where you see indigo was used in the clothing of wealthy people… Artworks and historical artifacts provide glimpses into this forgotten history, reminding us to reflect on the stories they hold.

Galleries around the world contain collection that show the forgotten history of indigo; slave owners dressed in indigo dyed clothing with their slaves in the background, works often depicting the Virgin Mary in blue, Napoleon’s Army in Blue. In 2018, micro- and macroscale techniques were used to study Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring and they revealed that indigo was used in the background.3 Consider this history the next time you’re looking at paintings or creating your own works of art containing indigo.

Environmental Impact and Sustainable Solutions

The process of dyeing textiles with indigo is extremely resource-intensive, polluting and harmful to workers, particularly when done on an industrial scale. Modern indigo dyes are derived from crude-oil, which have an environmental and geopolitical cost. According to the World Bank, 17-20% of industrial water pollution comes from textile dyeing and treatment. Seventy-two toxic chemicals in our water come solely from textile dyeing, of which 30 cannot be removed.4

In the 1970s and 1980s the jeans capital of the world was located in El Paso, Texas. By the mid-1990s El Paso’s jeans industry was in steep decline—a pair of jeans could be made in Xintang, China for a quarter of the price and in a place with few pollution controls. A pair of jeans can consume over 3,700 liters (975 gallons) of water and produce over 33kg of carbon.5 The water in the area is so polluted, smelly and black that homes are worthless. It is the source of drinking water for several million people, but the water is not drinkable and is carcinogenic to humans. This same issue is also happening in densely populated Bangladesh where pollution is increasing because of the political and economic power of the textile industry.6

Shaping a Colorful Future Through Engineering

Growing environmental awareness and concern for health risks have prompted a search for alternative materials and manufacturing methods that are eco-friendly. Fibershed says to make plant-based indigo a viable option, a change in consumption patterns is necessary. This change involves cultivating a deep appreciation, respect, and comprehension of the resources, skills, and labor involved in its production. Additionally, it requires exploring sustainable methods for cultivating and processing natural indigo, as well as devising solutions for responsibly managing its waste products.7

Currently there are three ways to produce indigo: natural plant-based methods, synthetic petroleum-based methods currently used which cause health and environmental damage, and the microbial-based methods using genetically-modified microorganisms.8 Huue is one company that has developed in a lab custom microbes that produce indigo as part of their biological process. The microbial methods involve inserting the genes for indican production from plants into microorganisms that can then be cultured and concentrated. The environmental impact of the microbial method is unclear at this time.

Indigo is insoluble in water, and many studies are underway to find a solution to water pollution including electrochemical reduction9, modified graphene oxide10, and microbiological decolorization systems, in particular basidiomycete fungi native to Brazil is being studied.11 Researchers at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE), have created a new mussel-inspired nanomaterial that they say can clean up these dyes and other pollutants from industrial wastewater.12 So far they have found no side- effects and they are looking to partner with industries to test it in the field. And researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have developed a new method that can easily purify contaminated water using a cellulose-based material. It’s a biobased material, a form of cellulose powder with excellent purification properties that can adapt and modify depending on the types of pollutants to be removed. The research was conducted in collaboration with the Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur in India, where dye pollutants in textile industry wastewater are a widespread problem and field testing is ongoing.13

Plant-Based Solutions

The demand for synthetic petroleum-based dyes is so high that in order to replace it with natural indigo production, it would require 2 million acres of cultivated land, or an area of a square about 56 miles per side.14 Currently natural indigo pigment represents less than one percent of the indigo dye produced and used worldwide and thus natural fabrics and dyes are a luxury product not available to the mass market. Some companies are working to make natural dyes and fabrics more affordable.

Stony Creek Colors in Tennessee is working with family farms to transition from growing tobacco to growing indigo as a regenerative rotational crop. They contract with farmers (in TN and FL and Mexico) to cultivate about 180 acres of indigo. With partners they will produce enough indigo for more than 60 million pairs of jeans per year by 2027.15 Their proprietary seed genetics and plant breeding program increases yield and dye content, and the dye extraction process is safe and transparent. Some of the brands using their indigo include Levi, Wrangler, Lucky Brand, Patagonia, Nudie Jeans, Taylor Stitch, J. Crew. They also sell dye to artisans for at-home and small business creations.

Fibershed is a Northern California company that asks “Who grows your clothes?” They support an independent network of farmers, ranchers, designers, sewers, weavers, knitters, felters, spinners, mill owners, and natural dyers in growing and manufacturing that builds up rural communities. They have done extensive research on indigo’s climate beneficial farming practice, a landscape assessment on current dye practice (synthetic & natural), and in an in-depth analysis on planting, harvesting and pigment extraction from plant-based indigo sources. All of these reports are available at their website. They believe we need a three-step indigo process in a closed-loop system that moves from soil to dye to textiles and back to soil. This would reduce the large amount of water needed to produce natural indigo, and it would eliminate its highly alkaline and dye-laden wastewater.16

The National Resource Defense Council’s Clean by Design program uses the buying power of multinational corporations as a lever to reduce the environmental impacts of their suppliers abroad. They released a paper in 2012 Dyehouse Selection: A major opportunity to reduce environmental impact. They discovered that half of the fabric dyed worldwide comes out the wrong color and needs a correction. The paper discusses the environmental impacts of dye mills and offers ten best practices to reduce inefficiencies (in energy, water, and chemical usage) and waste and thereby reduce the environmental footprint while saving the factory money.

Ways You Can Help

As individuals, there are ways we can contribute to a more sustainable indigo industry. Supporting brands that prioritize natural indigo dyes and sustainable practices helps create demand for responsible production. Additionally, learning about indigo’s history, raising awareness, using plant-based indigo for your own creations, can lead to a deeper understanding of the social and environmental implications of our consumption choices.

Read Books

Indigo: The Colour That Changed the World by Catherine Legrand

Color: A Natural History of the Palette by Victoria Finlay

Eliza Lucas Pinckney: Indigo in the Atlantic World – paper by Eliza Layne Martin

Harvesting Color: How to Find Plants and Make Natural by Rebecca Burgess

Watch or read online

The River Blue. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/riverblue

Indigo: What can one colour tell us about a painting? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDQ6p9M9gdU

https://media.greenpeace.org/archive/Fabric-Dyeing-Factory-in-China-27MZIF34P0NP.html

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/south-carolina-indigo-artists-enslaved-plantations

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/indigo-making-comeback-south-carolina-180980987/

Buy from eco-friendly brands

https://fibershedmarketplace.com/

https://www.dl1961.com/

https://www.nudiejeans.com/

Classes and supplies for growing, dying, creating with indigo

https://fibershed.org/programs/education-advocacy/learningcenter

CHI Design Indigo

https://www.stonycreekcolors.com/

Instagram

Pigment Hunter https://www.instagram.com/p/CScdV0HpmKq/

Indigo Grower https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/indigogrower/

Ricketts indigo https://www.instagram.com/rickettsindigo/

Hiroyuki Shindo https://www.instagram.com/browngrottaarts/

Karen Bauer is an Urban & Regional Planner, designer and bird naturalist, with endless curiosity about our colorful environment. Follow her adventures @creating.art.together

Sources:

1 Loon, A. van et al. (2020) Out of the Blue: Vermeer’s Use of Ultramarine in Girl With a Pearl Earring – Heritage Science, Springer Open. Available at: https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-020-00364-5 (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

2 Loon, A. van et al. (2020) Out of the Blue: Vermeer’s Use of Ultramarine in Girl With a Pearl Earring – Heritage Science, Springer Open. Available at: https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-020-00364-5 (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

3 https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-020-00364-5

4 Francis, K. (2021) Indigo: What Can One Colour Tell Us About a Painting? | National Gallery, YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDQ6p9M9gdU (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

5 Loon, A. van et al. (2020) Out of the Blue: Vermeer’s Use of Ultramarine in Girl With a Pearl Earring – Heritage Science, Springer Open. Available at: https://heritagesciencejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40494-020-00364-5 (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

6 Kant, R. (2011) Textile Dyeing Industry an Environmental Hazard, Natural Science. Available at: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=17027 (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

7 Lee, C. (2022) Inside China’s Plan to Clean up its Textile Industry, Fair Planet. Available at: https://www.fairplanet.org/story/inside-chinas-plan-to-clean-up-its-textile-industry/ (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

8 Yardley, J. (2013) Bangladesh Pollution, Told in Colors and Smells, The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/15/world/asia/bangladesh-pollution-told-in-colors-and-smells.html (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

9 Wenner, N. (2017) The Production of Indigo Dye From Plants – fibershed.org. Available at: https://fibershed.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/production-of-Indigo-dye-aug2018-update.pdf (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

10 Werner, N. and Forkin, M. (2017) The Production of Indigo Dye from Plants – fibershed.org. Available at: https://fibershed.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/production-of-Indigo-dye-aug2018-update.pdf (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

11 Balan, D.S.L. and Monteiro, R.T.R. (2001) Decolorization of Textile Indigo Dye by Ligninolytic Fungi, Journal of Biotechnology. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168165601003042 (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

12 Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Volume 117, 2023, Pages 21-37, ISSN 1226-086X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2022.10.008.

13 Doralice S.L. Balan, Regina T.R. Monteiro, Decolorization of textile indigo dye by ligninolytic fungi, Journal of Biotechnology, Volume 89, Issues 2–3, 2001, Pages 141-145, ISSN 0168-1656, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00304-2.

14 Cairns, R. (2023) One-fifth of water pollution comes from textile dyes. but a shellfish-inspired solution could clean it up, Yahoo! News. Available at: https://news.yahoo.com/one-fifth-water-pollution-comes-083404588.html (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

15 Technology, C.U. of (2023) New Wood-Based Technology Removes 80% of Dye Pollutants in Wastewater, Newswise. Available at: https://www.newswise.com/articles/new-wood-based-technology-removes-80-of-dye-pollutants-in-wastewater (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

16 Wenner, N. (2017) The Production of Indigo Dye From Plants – fibershed.org. Available at: https://fibershed.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/production-of-Indigo-dye-aug2018-update.pdf (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

…when prices were high, indigo dyestuff could be exchanged for slaves; it is said that a planter in South Carolina could fill his bags with indigo and ride to Charleston to buy a slave with the contents, “exchanging indigo pound for pound of Negro weighed naked.”

https://laits.utexas.edu/cairo/files/ExplorersTradersImmigrantsFull.pdf

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.

Plantings

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Heirloom Tomato with Fermented Blackberries and Roasted Kale Stem Oil

By Tessa Liebman