Working the Garden and Spirit

An Interview with Maria Rodale

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

“Go outside. Put your hands in the dirt. Grow something.”

Maria Rodale

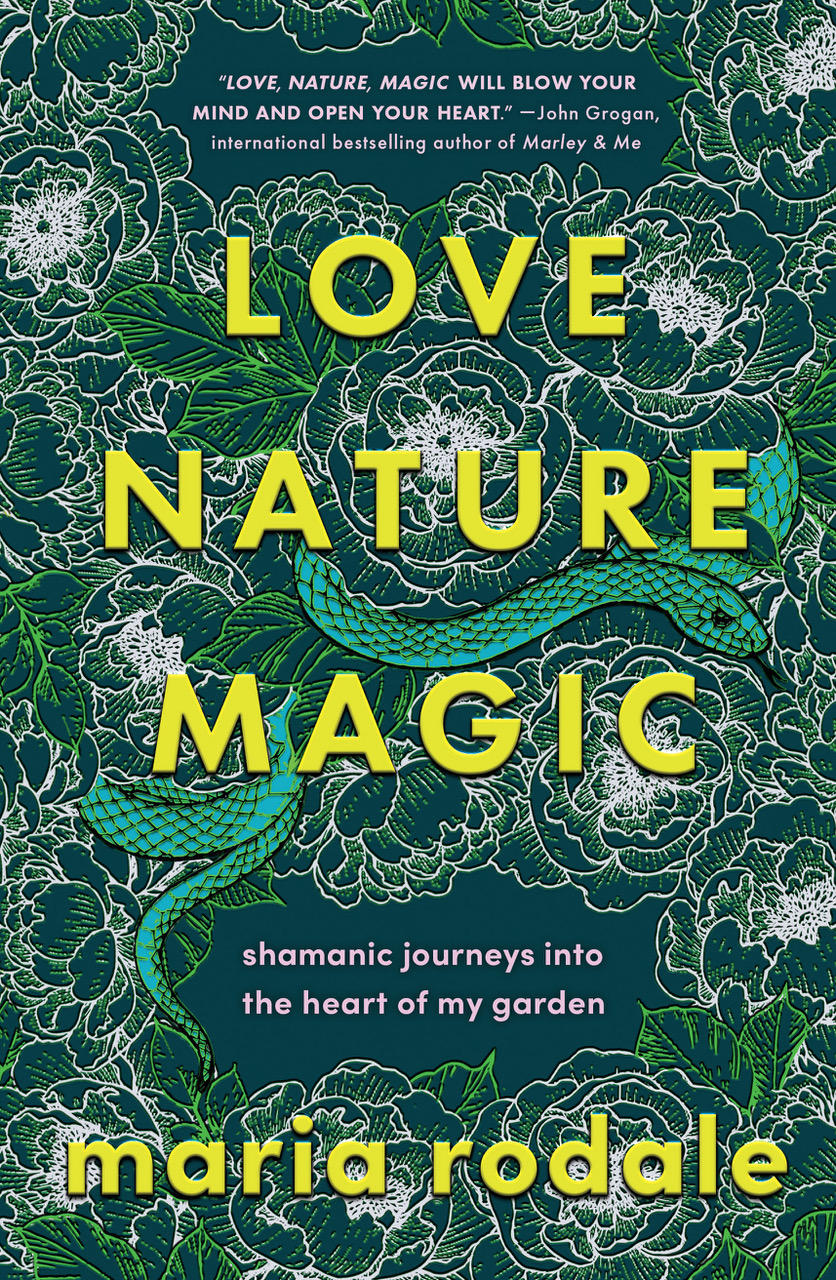

Maria Rodale freely declares her love of nature and distain for chemical use in gardening and why wouldn’t she, she is the third generation of the Rodale’s who pioneered organic gardening in the United States. Her grandfather, J. I. Rodale founded Rodale Inc. a publishing company focused on health and wellness content in 1930 before founding the non-profit Rodale Institute in 1947 in Emmaus, Pennsylvania. Her father Robert also wrote many books on regenerative agriculture, organic gardening, and nutrition, and became the President and CEO of Rodale Press. Maria joined Rodale Inc. in 1987 and she contributed in many capacities prior to becoming CEO and Chairman in 2007. She also serves on the board of the Rodale Institute and is a former board chair for the organization. Her devotion to regenerative farming and reversing climate change has garnered her many awards including the National Audubon Rachel Carson Award in 2004. In Maria’s latest book Love Nature Magic (signed copies are available in our store), she takes us with her on her Shamanic journeys that involve a shifted state of consciousness to connect with the wisdom and insight of plants and animals that she interacts with in her garden, touching evidence of the relatedness of all things. Maria describes a shamanic journey as “a drug-free way of going inward to seek understanding of the outer world by speaking directly with spirits in other realities. You can read an excerpt of Mugwort, a plant she started out trying to eradicate until she came to understand it, in this issue of Plantings.

Maria has said that gardening and landscaping are both her art and a “creative collaboration with the greatest artist of all—nature.” I saw that presence when I visited her at the end of May at her home and garden in Pennsylvania, located close to where she was born and raised. She prepared a delicious garden-fresh lunch for us that we thoroughly enjoyed before we sat down to talk.

Gayil Nalls:

How does your garden express your creative skills and your imagination?

Maria Rodale:

I love to look at beautiful landscapes. I’ll often just daydream about what I’d like to see from a window, or how I’d like to experience the land, and then I’ll really pay attention to what the land seems to want. I’ll get out my graph paper, and my markers, and pens, and I’ll sketch things. I have maps I’ve drawn of my design ideas. I look at flow. One of my proudest achievements is, I have a signed certificate from Bill Mollison, who’s the founder of permaculture, and he teaches this whole practice of landscaping where you consider everything. You sit, you meditate, you think about, “Okay, where are we here? Where are we in the landscape? Where are the mountains? Where’s the sun? Where’s the wind?” And it considers all the aspects of the environment, but ultimately, it’s what I want to look at, and what I love. I love roses. I love trees. I love color.

What does the word garden mean to you? What is gardening an act of for you?

It’s an act of creating an Eden, really, and it’s a collaboration with nature. That’s what I’ve learned as an artist. When you’re painting on a canvas, you’ve got control of the brush and the paint. When you’re creating with nature, nature talks back, so, “Oh, I didn’t plant this here, and look what’s growing,” and, “Oh, this plant is doing well, and this plant isn’t.” It’s learning how to collaborate with nature and create bountiful, beautiful food, shelter, and pleasure. All the things that you need for everything to be happy, including yourself.

How do you define Garden?

It’s where humans interact with nature. Wildness is where humans don’t really interact. A garden requires human interaction.

Would you say you have an aesthetic?

The first gardening book I wrote was in 1997, and I defined my aesthetic then. I had this realization the other day, “Oh, I’m still doing this,” which is what I call wild formal. I have metal edging to delineate between the grass and the beds but once you cross the metal edging into the beds, pretty much anything goes in there. I’m articulating the pathways and the shapes, but I’m not being overly fastidious about what’s inside those shapes. Inside the garden beds, there’s a constant process of things dying, and new things popping up that I didn’t expect.

It’s like a form of your canvas in there.

Right. And being happy with whatever happens.

Do you work into some of these locations? Rework them?

I’m constantly reworking, because there are constantly things changing. For example, one day I might turn round and say, “Oh, look. Those bushes died. I’ve got to take those out. Now what?” Or, “I really want to plant raspberries, or actually black raspberries, but I don’t have space, so I have to make a bed for them.” It’s this very fluid process that’s never ending. It’s never ending, because next year, something else will die, and something else will grow up, and I’ll have to deal with it.

With this life experience that you’ve had, and then later with your journeying, did that change your philosophy of gardening?

Completely. I would say my grandmother’s style was very European. She had traveled a lot. Even though the hippies made organic famous, my grandmother was not a hippie. She was before hippies. Her aesthetic was very European. My mother’s aesthetic was very Pennsylvania Dutch, which is German. She kept everything incredibly tidy and orderly. That was the training I had, and I was an aggressive weeder. This journey taught me to appreciate and respect the plants that I hadn’t planted myself, the plants that other people would consider weeds or invasives, but now have important purposes in the landscape. The difference in my gardening style is also a result of climate change, because my mindset is “What’s more important, that something looks tidy, or that we’re actually storing carbon in the soil?” The plants do that independently. So, if I can just let the plants do what they need to do, and they still let my roses and peonies bloom, and my vegetables grow, then it’s a win-win situation.

In your book, I began to hear a very moral voice, that a lot of your practices are grounded in principles, morality. Is that inherent with who you are, or is this something that’s developed towards your respect for nature, and your gardening practices?

Where do we learn morality? I do think it was part of my upbringing. Integrity has always been essential to our mission as a family, and a business. However, where it really developed, solidified for me was, when I began studying about all the different religions and religious traditions, it made me a firm believer in karma. A very firm believer. Why do something that’s going to come back and bite you later? That’s where my German, Pennsylvania Dutch efficiency comes in. It’s just not worth the risk to do something that’s going to come back to bite you later. Stay on the path, do the right thing as best you can, and life takes care of itself then. Is that morality?

I think that’s a moral course. Based on your book, Love, Nature, Magic, I imagine the greatest rewards for your gardening are the pleasure and the friendship and conversation and even the emotional connection, not only to these plants, but your many inner selves, that you harbor. You manifest these personalities of these plants. So, I was wondering if this is a way that you touch and find evidence of our connectedness to all things.

Definitely. I think what I’ve learned and seen is that the more you pay attention to nature and the more you embrace it, the more it’s not just me conversing with it, it converses with me. It makes life so much more enjoyable. For example, I have these little foxes that live near my garden. There are two families, that live on different sides of the property. You have foxes on one side, foxes on the other, and it would just bring me so much joy to watch them come together. I’m not afraid of them. I’m not going to eat them. I’m not going to kill them for furs. Although I did save the tail of one that died. It’s very soft.

Will that become part of your shamanistic work?

I did do a journey to the fox after the one died, but it was very, very short. The mother fox said, “life is fleeting, enjoy every moment.”

You have almost an inherited need to garden. Do you know if that is why you garden?

What was interesting about my family history is that, while my grandfather and father are considered the founders of the organic movement, they weren’t farmers or gardeners. My grandfather always wore a suit. He employed people to do the farming for him to enact his ideas, but my grandmother and my mother were hands and knees in the dirt, building, creating. My grandmother was a painter, my mother was an art teacher, and her mother was also an artist. I grew up in these incredibly beautiful places that my grandmother and mother created, and I was put to work at an early age, but I just loved it. So, I don’t know where the need to garden came from, but yes, it’s probably inherited.

I enjoyed seeing your thriving garlic, can you tell me about that plant?

My former father-in-law, who has now passed away, he, more so than my father and grandfather, was a gardener and a forager. His parents came from Italy, so very Italian, but he was born American. He was a very traditional, humble guy who just loved to garden, cook, and forage things like mustard greens and what he called Gardooni, which was really burdock stems.

But he always grew garlic. And it was the garlic his father brought from Italy. I never really grew it for many years, got divorced, but then, at his funeral there was a basket of his garlic cloves. Everyone was encouraged to take some and plant them, it was a parting gift of sorts. So, I took some and thought, “I’m going to do that.”

You plant the garlic in the fall and it’s super easy. You just take each clove out and stick it in the dirt. By spring it’s coming up and by mid-summer it’s ready. I’ve been doing that now for probably six or seven years since he passed away and it’s the easiest and most loving thing I grow.

What other regular vegetable plants do you grow, and for what reasons?

Well, I’ve simplified. I’ve stopped trying to grow everything because I’ve realized I do some things better than others. Some things I just can’t do, some things I don’t even like. My main thing is peas because I love fresh shelled peas and you can’t buy those in the stores really. So those are just for raw eating. I really like growing tomatoes, and then I make sauce (with my garlic, of course) which I then freeze to last the whole winter. And potatoes, I like growing potatoes because I like blue potatoes and I just like the taste of fresh potatoes. I grow other kinds too, the kinds that you can’t get in stores. I’m not trying to replicate what you can buy at the supermarket. I grow a lot of basil and I make pesto and freeze it. Normally my explorations are inspired by tasting something that I’ll then want to try and grow myself. There’s a place that is a garden store restaurant, and they have this green chickpea hummus which is truly delicious. Green chickpeas are chickpeas that are harvested young so that they have a unique sweet nutty flavor and buttery texture. I wanted to make the hummus at home so I wondered, “Where can I get green chickpeas?” I couldn’t find them anywhere and then I remembered that I had been to Saskatchewan, Canada, which is an area where a vast majority of chickpeas are grown. I thought, “Well, if you can grow chickpeas in Saskatchewan, why can’t you grow them in Pennsylvania?” I bought some and planted them last year and they grew. Now, I have a whole bed of chickpeas that I harvest early for the delicious green chickpeas that you can’t buy in stores.

Here is my recipe for green chickpeas. It’s really simple.

- Pick the chickpeas when the pods are still green.

- Shell the chickpeas and boil them in water for a few minutes.

- Drain.

- Add olive oil and salt and pepper to taste.

To make hummus just put it in the blender. However, save a step and just eat them whole. The taste is sublime.

As a gardener with so many years of experience and a lifelong passion for organic gardening, do you have any advice for other gardeners?

Well, I think what I’ve noticed is that a lot of people are afraid. They’re afraid of things going wrong, diseases and bugs, and I was afraid too, I’ve always been a fearful kind of person. I used to worry, “Uh-oh, if I eat this, will I die?” The good news is there are so many resources now with apps and the internet which gives us the opportunity to learn anything and everything. So, my advice would be, have fun and play and experiment and see what you can grow. I can’t grow carrots, they won’t grow for me, but lettuces I can grow. Find out what you are good at doing and don’t worry about what you’re bad at doing. Don’t worry if some of your plants die because things are constantly dying. Just have fun learning and exploring and eating what you’re able to grow.

We’ve talked about food as medicine. Is there anything that you grow just because you know you need it?

I know I need fresh food. I know I feel better when I have fresh food. Winter is hard for me when there’s not fresh food and fresh herbs such as basil and parsley. I need the taste of freshness, but I’m not really a medicinal type of person, I probably should be but, I’m not.

What’s your favorite herb?

That’s not a fair question.

Like picking one of your children?

Yeah.

If you had to?

Well, I like purple basil because I like the way it tastes in salads, and you can’t buy it in the store usually. I like lovage because it’s great in mashed potatoes, but also because the German word is liebstöckel, which is I heard once, translates to love stick, which makes me laugh.

There’s a lot of conversation about taking care of invasives and how to approach these plants. It seems the conservation community is very divided about how to handle this, whether there’s ever a good reason to use chemicals. As an expert on permaculture, how do you weigh in on this?

Well, that was one of my big learnings from doing my journeys, was that the emphasis and focus on invasives is very similar to racism or anti-immigration policy. Although many conservationists are also liberals, being liberal doesn’t necessarily change that we’re all capable of being intolerant. A lot of these invasive plants didn’t ask to come here but were brought here by humans for a specific purpose and now they’re just doing what they are meant to do. For example, mustard greens demonstrate how things are out of balance and science can confirm it. If we managed our deer populations appropriately, we ate venison instead of cows from feedlots, we wouldn’t have a mustard green problem and subsequently, a tick problem. Historically, science and academia have been very reductionist in looking at narrow categories of things, but you can’t understand how to solve these problems unless you look at the whole picture of how things in nature are interacting and interrelating.

A lot of people feel that with climate change, it’s important to have native plants that have the best capacity to adapt to the environment, and that invasives are smothering these or suppressing them so removing the invasives are important so that the natives can thrive.

I don’t quite agree with that. I mean, if somebody wants to do all that work, great. But what really needs to happen is we need to let nature take care of itself and get out of its way. And like I said, every plant has a purpose and has an intelligence about what that purpose is. A lot of times we think we know what nature needs. We think we know what the native plants are, but maybe those native plants have migrated because the climate has changed. Maybe they’re going someplace else where they can be happier. Maybe if we just get out of the way, they would come back on their own. Because that’s what birds do. They eat seeds and they poop them out, and they plant things. I don’t completely disagree, but I also think nobody should ever use chemicals ever, for any reason. That is the most stupid thing that we could do.

Through your experiences, gardening, landscaping, and journeying, are there any other personal or horticultural philosophies that you’ve developed that you feel strongly about?

Well, I do think permaculture is a great way to look at a whole environment. The basics of that are really observing the world around you and trying not to put a French formal garden in a woodland setting. Working with what you have and where you are, including the idea of zones; where closer to the house you have the things that you want to eat or pick, and then farther out you let it go wilder. I personally believe there’s a lot of good to permaculture design.

What are other principles of permaculture that you pass on?

Observation. Zones. Working with what you have. Managing the landscape for water–for instance building swales to catch the water so it’s not causing erosion. … If you look back in the olden days, a farm would have hedgerows and that would also prevent erosion and create habitat for wildlife. Now with commercial farming, the land is designed more for tractors, so you have these wide open, humongous fields with nothing to break the wind, nothing to catch the water. Then you have runoff. And if you’re using chemicals, there’s even more runoff.

My other philosophy is regeneration. Organic is essential. Organic is no chemicals at all. Regenerative organic is the humane treatment of animals and fair trade and social justice for the people working for you. So, it’s a whole philosophy about not just how you treat nature, but how you treat wildlife and humans. Whether it’s a farm or a garden or a back yard, everything should be in harmony and balance and treated with kindness.

Is there anything else that would guide and encourage other gardeners? Something important that you’ve learned and would like to share.

Relax. I’ve learned from working with shamans that I can’t take personal responsibility for saving the world, it’s going to take a communal effort from all of us. So, we can start where we are with our own backyards, our landscapes, our kitchens, our houses, and do the best we can to create the kind of world we want to live in.

Ultimately, that’s what I’ve tried to do here. My garden reflects the world I want to live in. I’m very happy to visit other worlds, but this is home and I want to live here. Anyone is always welcome to come visit and enjoy it, but your world doesn’t have to be like mine because everyone has a different vision of what kind of world do they want to live in. And that’s okay. That’s the beauty of diversity.

Do you have a favorite plant?

I mean, I do love roses. But I love trees. I love everything.

Maria Rodale is an explorer of nature and an award-winning activist in its behalf. She is the author of many books including a children’s book series and remains active in the Rodale institute. Subscribe to her Substack Newsletter: Life. Unfiltered.

Gayil Nalls, PhD, the founder of World Sensorium / Conservancy and editor of Plantings, is an interdisciplinary artist, theorist, and gardener.

Plantings

The Ecological Impact and Potential of the American Lawn

By Jake Eshelman

Viriditas: Musings on Magical Plants: Artemisia vulgaris

By Margaux Crump

Green Oases:

NYC’s Community Gardens

By Olivia Mermagen

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Heirloom Tomato with Fermented Blackberries and Roasted Kale Stem Oil

By Tessa Liebman

A limited number of signed copies of Love Nature Magic by Maria Rodale are available in our store.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.