Alexanda Climent on an expedition in 2021 standing with a Nazareno tree. Nicholas Mehedin

Mind the Darién Gap: Saving Central America’s Endangered Rainforest

By Alexandra Climent

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Quite recently, “The Darién Gap” has entered the public lexicon due to high profile reporting on migration. Global migrants and refugees must pass through the Darién to cross from South America to Central America. This dense tropical rainforest is infamous for being the most dangerous jungle in the world, but the reasons why depend on who you ask. The hardships reported from this brave endeavor range from threats of kidnapping, narcotics and human trafficking assault, and theft, not to mention the natural challenges of crossing a jungle loaded with venomous snakes, poisonous insects, raging rivers and mudslides. What we don’t hear about the Darién is how it stands out as one of the most biodiverse tropical rainforest habitats in the world.

Envision a place where human interference is minimal, time seems to be at a standstill, and the only visible movement comes from the graceful locals gliding along the winding rivers. The reasons why are fascinating. The creation of this relatively young land-bridge starts with two previously unconnected land masses, North America and South America. If you look at a timeline of earth’s geographical history, The Darién appears towards the very end – making it one of the newest places on earth. Unique geological phenomena along with the rise and fall of prehistoric sea-levels left plants and animals stranded on mountain tops, leading to a breathtaking number of endemic species. With prehistoric sea-levels rising and falling overtime, many species had become stranded on mountain tops and migratory pathways for animal and plant species and in between the Americas formed.

Perhaps one of the most meaningful developments out of the Darién’s formation was the migration of the indigenous peoples of the Emberá, Wounaan and Kuna into Central America. When you ask them what they consider dangerous in their ancestral lands they will likely smile and tell you that there are no issues here. They have coexisted with the hardships of the rainforest for centuries, learning the importance of a symbiotic relationship with the species surrounding them. The only fear they have is the loss of their sacred land. In 1983, The “Emberá-Wounaan Comarca” was formed, preserving the land of these communities. Unfortunately, many more indigenous communities were left outside these protected areas with nearly over a million acres remaining unprotected. For these people, the struggle to safeguard the forest and its biodiversity means life or death, and losing the rainforest means losing their home, identity, culture, and way of life.

Unlike the indigenous way of living, our global economy has demanded the constant extraction of our earth’s resources to satiate our desire for constant consumption. We do not simply take what we need from our earth with humility and respect, but we exploit resource dense areas and its peoples. Recognition of historical colonialism and its systemic roots is not enough, as its tendrils continue to threaten unique vulnerable communities like the Emberá and Wounaan that have lived in the region for centuries. Most of the indigenous cultures in the Darién region are still passing on their heritage, traditions, and culture to the next generation, so they remain interlinked with the ecosystem of their ancestral lands. Their intimate and deferential relationship to nature grew a profound intuition regarding the utility of the plant and wildlife species found in their rainforest. They still understand the reciprocity of all things and that their actions have consequences – ripple effects throughout the jungle. From working with these people to conserve the forests, I have come to believe we need to restore this ancestral philosophy to the consciousness of all people. We all need to come back to nature in order to stop our disastrous effects on the planet.

My personal interest in the Darién started years ago when my artistic practice led me to Panamá. Previously working in South American rainforests to find fallen trees, I had developed an intense connection to the material I was collecting and the place it came from. The process of being enveloped by life in a remote jungle was almost an out of body experience. The connection between me and the Earth felt so deep, but the mass deforestation I first witnessed from an airplane window was encroaching on that love. The deforestation in the global south and particularly Panamá has been rampant. Unknown numbers of endemic native trees were being lost and I knew the best place to find them would be in Darién – the only problem was getting there. My first expedition to the Darién was by sailboat, and even when I finally arrived and saw the foothills from the boat, it looked impenetrable. It took a lot of convincing to have any Panamanian take me any deeper as many of them fear the treacherous and lawless landscape hidden inside.

Once I was finally able to embark into this primordial jungle I was overwhelmed with the ecological diversity. On just one expedition through the Darién alone, we ventured through swampland, lower montane forest, dwarf forest, cloud forest, and eventually reached a remote dry forest along the Pacific coast. From sea-level to its highest peak in Cerro Tacarcuna, the Darién boasts an extraordinary variation in plants, animals, water, soil, and atmosphere. You would think such a unique spot in the world, with so many rare living things, would be heavily researched by scientists and explorers, but in truth, the area remains highly unexplored. One of the least explored areas of the regions are cloud forests, which is likely due to their high elevation and thus the practicality in exploring them. These ecosystems, where low clouds hover and condense in the canopy of the trees, are suspected to contain a bulk of the undiscovered endemic species, and as climate change disrupts other ecosystems in the jungle, tropical hardwoods have been migrating to higher elevations in these cloud forests. This place is a tiny fraction of what is left of cloud forests in our world. To protect some of the rarest and most endangered tree species on our planet, this is the place to start.

Tropical hardwoods are the backbone of the rainforest’s ecosystem. The loss of just one tree species causes an enormous blowback that directly affects the livelihood of the plants and animals who call them home. We often see the protection of endangered animals take priority in mass initiatives, but protecting the endangered trees that inhabit them is the first line of defense. The indigenous deeply understand this harmonious relationship and can detect imbalances within the jungle. I deeply respect their concerns on environmental shifts and given the lack of research, their knowledge is an incredible source on which tree species are threatened. With the communal efforts of the indigenous communities and local Panamanians, I’ve conducted expeditions to find endangered tree species for nearly a decade. In 2022, I founded the not-for-profit Endangered Rainforest Rescue to broaden the scope of the project and to dedicate myself to its mission. The reforestation of vulnerable hardwoods within this ecosystem is the goal. We collect seeds, bark, leaves, and map species locations within the rainforest. With limited research this process is intensely laborious with even proper identification proving to be difficult. We also must work within the natural fruition cycles of different species, which is often asynchronous and demands multiple expeditions throughout the year. It’s a race against time to gather this information as each time I leave Panamá City the deforestation of Darién shrinks the jungle smaller and smaller.

Along the Pan-American Highway when you first enter Darién, what was previously swaths of rich biodiverse jungle is now endless rows of perfectly aligned teak plantations. These monocultures are invasive species produced solely as exported lumber that became popular in mid-century modern furniture. The effects of teak have been disastrous. As a non-native species, teak is devastating to the biodiversity of the area, harmful to the integrity of the soil, and disrupts plant and wildlife alike. Paradoxically enough given all these negative effects, teak plantations are labeled as reforestation efforts despite often requiring cutting down primary forest. Outside of dangerous for-profit monocultures, the development of pastureland has been a leading cause of deforestation for decades throughout Panama. Clear-cutting forest for cattle-grazing has depleted western Panama, and many farmers have migrated their operations into the Darién. As you continue down the Pan-American highway to its end in Yaviza, the effects of deforestation become increasingly pronounced. But this is where the road ends and our journey begins. We must protect this magical rainforest and combat these intrusive practices of deforestation. For me, the most dangerous part of the Darién is losing it.

The mountainous rainforest of the Darién Gap lies across two countries. Read WS/C’s pages on Colombia and Panama for additional insight.

Alexandra Climent is a New York-based artist, woodworker, and activist whose practice focuses on the endangered tropical hardwoods of Central and South America. She is the founder of Endangered Rainforest Rescue.

Formed in 2022, but in operation for the past seven years, Endangered Rainforest Rescue is a nonprofit dedicated to locating, sourcing, and tracking the presence of endangered hardwoods within the Darién Gap. This research is shared with the Yale Environmental Institute to survey the dramatic environmental changes within the remote jungles of Panamá. The communal aid of institutions, indigenous communities, and determined individuals, involved with this project define the humanistic potential for radical environmental change. Through those combined efforts, ERR has successfully reforested thousands of endangered trees on an organic protected farm in Central Panamá.

Plantings

The Real Magic Kingdom: Florida’s Corkscrew Swamp

By Gayil Nalls

Your Legacy on Earth May Be a Plant

By Veronique Greenwood

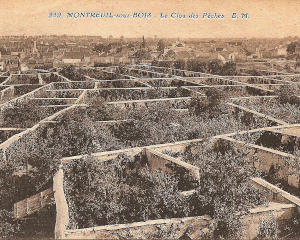

Fruit Walls: Urban Farming in the 1600’s

By Kris De Decker

The Goddess & The Rose

By Nuri McBride

Deirdre Fraser: The Plant Wizard of Pearl Morissette

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Cucumber and Sour Cherry Salad

By Deirdre Fraser

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.