The ancient Mesopotamians and Assyrians developed scented oils suitable for hair, beard, and body using fragrant plants, flowers, resins, and spices. Relief panel (detail), ca. 883–859 B.C., Neo-Assyrian. Gypsum alabaster. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr. 1932 CC0 1.0

Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim, The Oldest Perfumer on Record

By Nuri McBride

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

If you Google who the first perfumer in history was, you will find Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim; most likely, her name will be shortened to Tapputi. Online sources cast her as a proto-girl-boss, a kind of corporate feminist before the conception of capitalism. However, today let’s dig past the hype to look at the source material and see Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim not as the patron saint of corporate perfumery, but as one of many Assyrian workers who helped develop the bedrock of olfactory culture.

The Tablet of Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim

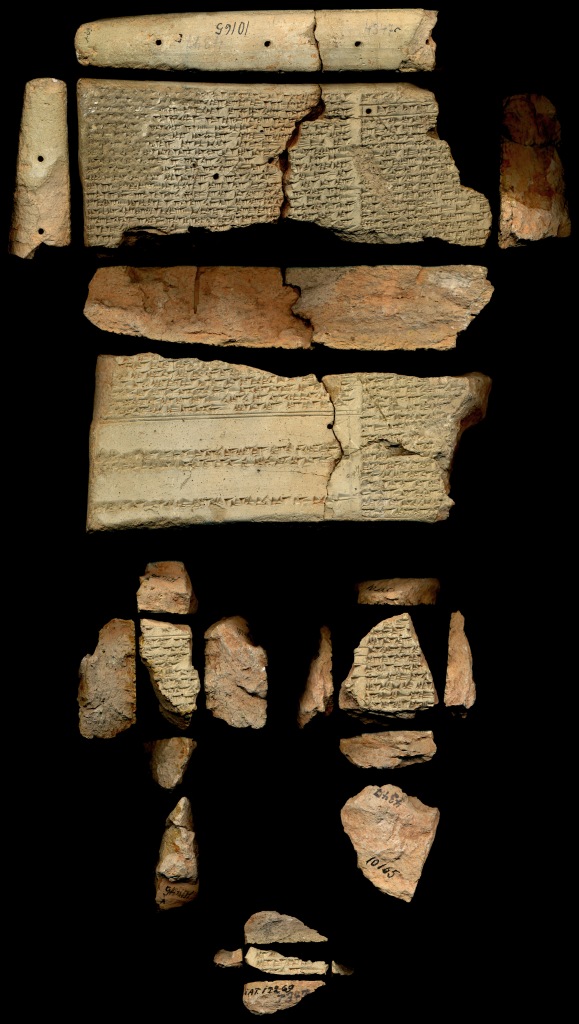

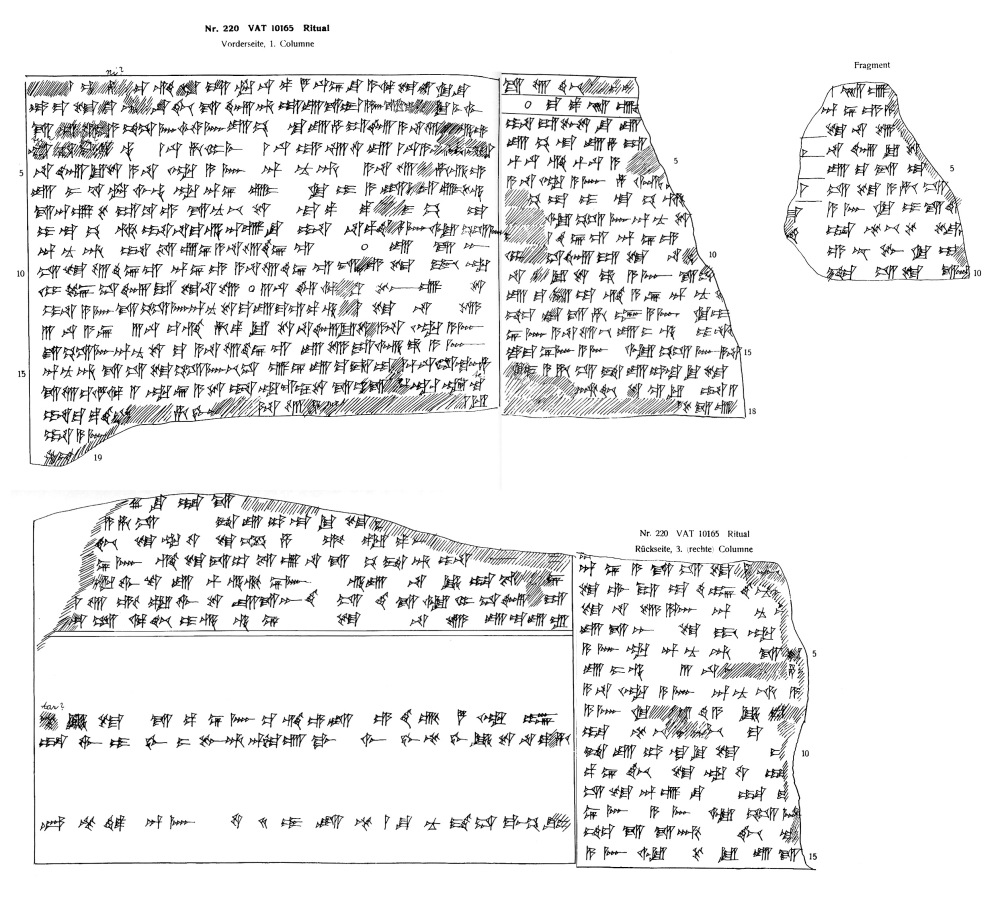

What we know of the first perfumer in the historical record comes from one tablet. The tablet, KAR 220, is a scholarly concordance on perfumery and was housed alongside other chemical texts in the ancient library of Aššur. It is written in Middle Assyrian and currently resides in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin.

The scribe of KAR 220 conveniently dated his work. The tablet was made in the 5th year of the reign of King Tukultī-Ninurta I on the 20th of the month of Muhur-ilani. (May 1239 BCE). The text includes the line, “from the mouth of the muraqqītu Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim.”

This line is the totality of the written record about her, but that one line says so much. This is the oldest named perfumer in the historical record thus far. She was a woman. We know this because her name and her title, muraqqītu, are both in feminine form.

The formula, translated in its entirety below, describes an early form of distillation, making it one of the first texts to describe a chemical process. Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim wasn’t a chemist, though. She was a perfume maker—a role in ancient Assyria that encompassed elements of art, cooking, medicine, and religion.

Her work was reserved for the elites of society within a tightly controlled palace economy. The tablet describes her perfume as, “fit for the king”. This language is important. From the perfumers’ guild of Mari, we know that only men usually made fragrances for the king. In Assyria, or at least under Tukultī-Ninurta I, women, too, made fragrances for the highest tier of society. Yet, she didn’t have the title of šangitû bit hilṣi (overseer of the perfumer’s workshop), so while her work was worthy of recording, she probably had a boss. It is unlikely she was at the top of the pecking order of the bit hilṣi; her title would reflect that.

The fact that Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim is named at all is significant. We have older perfumery documents from across Mesopotamia. However, palace workers, even skilled workers like perfumers, were often not named in written records. This was especially true of perfumers that came to Aššur through conquest. Often, they are referred to by their city or nationality of origin (example: the Assyrian perfumer).

Western Asian and Egyptian women were targeted for enslavement in Mesopotamia based on their perfume-making, cosmetics-making, hairdressing, cooking, and textile manufacturing skills. After all, one of their justifications for imperial expansion was access to goods and raw materials unavailable in Aššur. That also required the uprooting of skilled laborers familiar with those materials. While the number of translated Mesopotamian fragrance texts is limited, they overall give the impression that perfume-making was associated with foreign and exiled workers.

We see illusions of this even in the Bible. The prophet Samuel warns the Elders of being ruled by a foreign king.

“He will take your sons and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen: they will run in front…And your daughters, he will take them as perfume-makers, cooks, and bakers.” (1 Samuel 8: 11–13)

This text explicitly identifies perfume-making as a trade women engaged in to fulfill their obligations as subjects, just as their male counterparts would fill out the ranks of the king’s army. Perfumery was servant labor on an even footing with cooks and bakers.

We will never know if Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim was one of these taken daughters, a native of Assyria, or a willing immigrant to the capital city. Her name is Assyrian, but it translates to ‘the assistant of the Lady of the Palaces’. The Lady referenced here is the goddess Bēlet-ekalli, protector of palaces. This name probably wasn’t her given name at birth but, instead, a name adopted in imperial service, which was a common practice.

The Formula

The fragrance depicted on the tablet is an aromatic salve created by steeping botanicals through a series of oil and water treatments. This infused the oil with scent and thickened the product. While these techniques are quite rudimentary to today’s sophisticated production methods, we see the early forbears of enfleurage and steam distillation in this work.

It’s important to remember this formula is not being recorded because it was an innovation. It is not the first-ever perfume formula. This formula, instead, was saved for posterity. Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim worked within an established tradition that was already centuries old during her lifetime. The text is written assuming the reader is already familiar with these techniques.

Sadly, not all of the botanicals have been identified. The text is also damaged, with sections missing. A complete translation is impossible, but what we have is still illuminating.

“If you prepare flowers, oil, and calamus as a salve, and you have tested the flowers of the calamus and its green parts, you set up a … and distillatory vessel. You put good potable water … into a vat. You heat tabilu (an aromatic) and put it in. You put 1 qa (1 qa = approximately half a litre) hamimu (an aromatic), 1 qa iaruttu (an aromatic), 1 qa of good, filtered myrrh oil into the vat. Your standard in this is the water taken and divided. You operate at the end of the day and in the evening. It remains overnight.

It becomes steeped. You filter this solution … with a filtering cloth into a vat at dawn, on the rising of the sun. You clarify from this vat into another vat. You remove the minduḫru (type of particulate, sediment). You wash 6 qa of crushed cyperus root grass with the liquid mixture of these aromatics. You remove the paḫḫu (a type of particulate, course).

You put on top of this liquid mixture of aromatics, within a settling bowl: 6 qa of myrtle, 6 qa of calamus, crushed and filtered.

You measure out 4 seahs (1 seah = approximately 8 litres) of this liquid mixture that has steeped overnight.

At dawn, when the sun rises, you filter the liquid and these aromatics through a filtering cloth into a vat. You clarify the mixture by filtering it from this vat to another vat.

You examine the comminuted material. You remove its bad part. You filter this solution which you clarified into a distillatory vessel … 3 qa … You throw … balsam into this solution in the vat. You kindle a fire. When the solution is heated for admixture, you pour in the oil. You agitate with a stirrer. You scrape it off; you remove the tiṇtiṇu (a type of particulate, fine) … this liquid mixture … you filter it, and you clarify it.

… your liquid mixtures, those which you have clarified … you pour it out … you add 3 seahs of pirsạ duḫḫu (an aromatic) onto the top of this liquid mixture … When the oil, solution, and aromatics continue to dissolve, you raise the fire … You cover the distillatory vessel on top. You cool with water. When the sun rises, you prepare a container for the oil, solution, and aromatics. You allow the fire under the distillatory vessel to die down. You remove the distilled and sublimed substances from the trough of the distillatory vessel …

… at daybreak … the aromatics which have interpenetrated each other … fire rises … you cover the top of the distillatory vessel; you cool it off. You prepare a šappatu jar for reed oils. You lay a filtering cloth with a sieve across the šappatu jar, then, taking a little oil at a time, you strain it through the filtering cloth into the šappatu jar. You remove the dregs and residue left in the distillatory vessel.

Perfume-making recipe for 2 seahs of processed cane oil, fit for the king, according to the mouth of Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim, the perfume-maker: month Muhur-ilani on the 20th day of the 5th year; the eponymate of Šunu-qardu (Tukultī Ninurta I), the chief.”

The Fall of Aššur

For about 627 years, KAR 220 was housed in the royal library at Aššur. Then in 612 BCE, a coalition of Babylonians, Scythians, and Medes attacked the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The city of Aššur was only partially destroyed in the empire’s collapse, but the library was razed. The materials made of wood, wax, papyrus, and leather burned, but the fire essentially baked the clay tablets, making the air-dried clay stronger. The rubble protected the tablets from erosion.

Aššur would be rebuilt under the Achaemenid and Parthian Empires, but they never attempted to rebuild the library. By the middle of the Parthian Empire, no one living could read the tablets. Old Aššur would hobble along as a city, a ghost of its former glory, until the 14th century C.E., when the city was sacked for the final time by Tamerlane and depopulated. From the 14th to the 20th century C.E., KAR 220 waited under sand and rubble for humanity to relearn cuneiform, find her, and read her.

That wouldn’t be until 1903 when KAR 220 was found in the ruins of the library of Aššur by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft excavations. The tablet was translated in 1919 by the acclaimed Assyriologist Erich Ebeling. Most of our knowledge of Mesopotamian perfumery comes from Ebeling and a handful of other scholars devoted to the subject.

Survival Bias

Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim wasn’t the first perfumer ever. She wasn’t even the first female Mesopotamian perfumer. In fact, her name wasn’t even the only one inscribed on KAR 220.

There is another formula below hers in the concordance, but the person’s name is damaged. We only have part of the ending, -ninu. This ending indicates a female name, but without the lost fragment, we will never know who this person was.

The difference between being the mother of perfumery or a footnote in history is a crack in a clay tablet. This is the essence of survival bias. Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim is extraordinary because her name survived, which was totally by chance. The Assyrian perfumer’s name didn’t, -ninu’s name didn’t either, but they were just as crucial to the advancement of perfumery.

Of course, other Mesopotamian perfumers are just as fascinating as Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim. Still, they aren’t the oldest on record, and no one cares about their contributions to the art because they don’t hold that superlative. Tukultī-ša-šāmê was also a female Assyrian perfumer. Her ingredients list shows that she was producing over 100 litres of product per commission.

What we know about Tukultī-ša-šāmê is just as tantalizingly brief as what we know about Tappūtī Bēlet-ekallim, but people don’t write articles about #2 in the historical record. In making Tappūtī-Bēlet-ekallim an exception, we lose the voices of the thousands of collaborators who helped create the very idea of perfume. The advancement of knowledge doesn’t happen due to one exceptional genius, but through the contributions of many people working together over time.

Nuri McBride is a perfumer and writer, examining the cultural history of floral scent. She is the Program Curator for the Scent & Society lecture series at the Institute for Art and Olfaction

References

(EN) Baker, Heather (ed.). The Prosopography of Neo-Assyrian Empire. Vol. 2, part II, L–N. Helsinki: The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. 2001.

(FR) Bottéro Jean. Textes culinaires mésopotamiens. Mesopotamian Civilizations 6. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. 1995.

(EN) Budin, Stephanie L, Cifarelli, Megan, Garcia-Ventura, Agnes and Alba Millet, Adelina. Gender and Methodology in the Ancient Near East: Approaches from Assyriology and Beyond. 2019. pp. 155-157.

(EN) Cousin, Laura. “Beauty Experts: Female perfume-makers in the 1st millennium B.C.”. The Role of Women in Work and Society in the Ancient Near East, edited by Brigitte Lion and Cécile Michel, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2016, pp. 512-525.

(EN) Cousin, Laura. “Female Perfume-Makers in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Documents”. Second Workshop. Le Rôle Économique des Femmes en Mésopotamie Ancienne. Tokyo. June 2013. refema.hypotheses.org/806

(DE) Ebeling, E. “Mittelassyrische Rezepte Zur Bereitung von Wohlriechenden Salben.” Orientalia, vol. 17, no. 2, 1948, pp. 129–45.

(DE) Ebeling, E. “Mittelassyrische Rezepte Zur Herstellung von Wohlriechenden Salben (Fortsetzung).” Orientalia, vol. 19, no. 3, 1950, pp. 265–78.

(DE) Ebeling, E. Parfümrezepte und kultische Texte aus Assur, Sonderdruck aus Orientalia. Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, 1950.

(EN) Halton, C. Svärd, S (Eds.) Proverbs and Other Literature. Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Anthology of the Earliest Female Authors. 2017. pp. 187-209. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(FR) Joannès, Francis. La culture matérielle à Mari (v): les parfums. Pp. 251–270 in Mari. Annales de Recherches Interdisciplinaires 7. Paris: Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations. 1993.

(EN) Levey, Martin. “A Group of Akkadian Texts on Perfumery.” Chymia, vol. 6, 1960, pp. 11–19.

(EN) Levey, Martin. “Babylonian Chemistry: A Study of Arabic and Second Millenium B.C. Perfumery.” Osiris, vol. 12, 1956, pp. 376–89.

(EN) Levey, Martin. “Early Muslim Chemistry: Its Debt to Ancient Babylonia.” Chymia, vol. 6, 1960, pp. 20–26.

(EN) Levey, Martin. “Perfumery in ancient Babylonia”. Journal of Chemical Education 31 (7). 1954. P. 373.

(EN) Pedersén, Olof Archives and libraries in the city of Assur: A Survey of the Material from the German Excavations, Part. I, Uppsala, Almqvist & Wiksell, 1985.

(EN) Postgate, Nicolas. Bronze Age Bureaucracy: Writing and the Practice of Government in Assyria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2014

(EN) Raign, Kathryn R. “Finding Our Missing Pieces—Women Technical Writers in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 49, no. 3, July 2019, pp. 338–364.

(EN) Raign, Kathryn R. The Art of Ancient Mesopotamian Technical Manuals and Letters: The Origins of Instructional Writing, Technical Communication Quarterly, 31:1, 2022. pp. 44-61.

(AS) KAR 220. VAT 10165, VAT 10445, VAT 12269 (frag). Excavation no: Ass 04347c. Vorderasiastisches Museum. Berlin, Germany.

(UR) AO 29560. Richelieu, [AO] Room 236 – Archaic Mesopotamia (from the Neolithic to the period of the archaic dynasties of Sumer), Vitrine 3 Birth of writing. Department of Oriental Antiquities. Louvre Museum

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.