Corn Field in Arizona, 1941, Ansel Adams

The Power of Harmony: Musical, Spiritual and Environmental

By Gayil Nalls

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

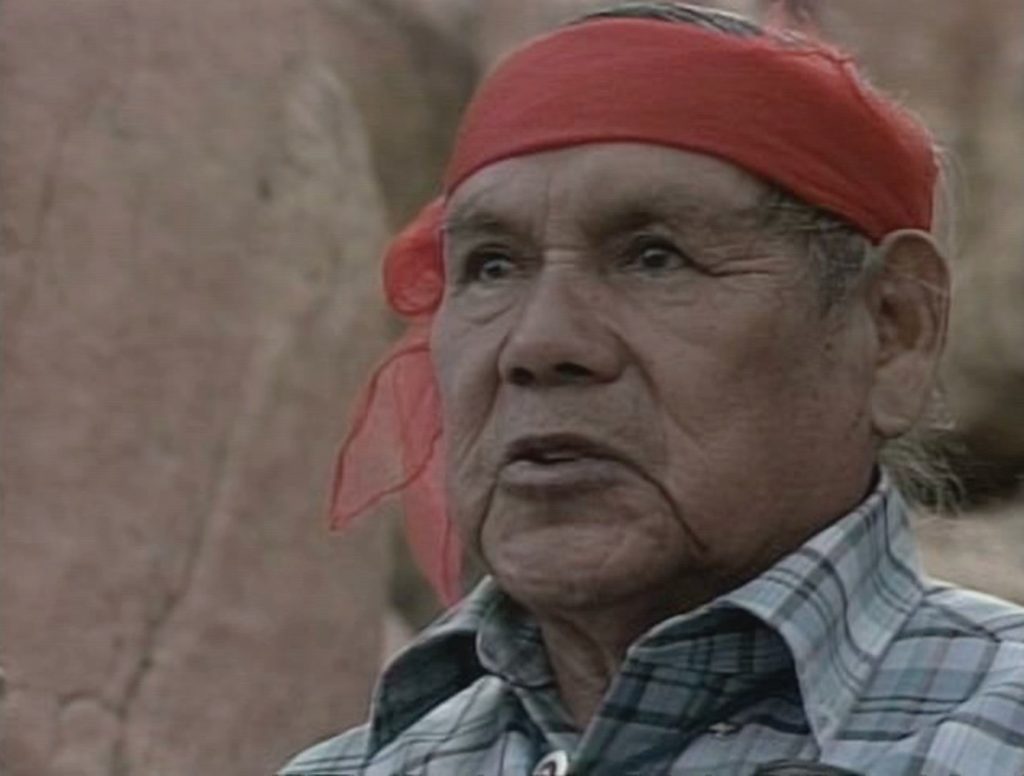

Thomas Banyacya (1909-1999), was a Native American Hopi traditional leader, and spokesman for the elders. When I arrived at his house on Third Mesa near Hotevilla one morning in 1989, I was welcomed by Thomas’ wife Fermina. She invited me to join Thomas for breakfast and in no-time she brought us black coffee and cold corn on the cob. I had arrived at Thomas’s for a meeting with him, the Hopi Elders and members of other tribes concerned about the state of the environment from the Pacific Northwest to the Mayan Lacandón Rainforest in Mexico, but our conversation quickly turned to the corn in front of us. Thomas explained that corn was central to the Hopi way, from birth until death. A conversation that continued throughout the next few days, as he taught me about the deep connection between Hopi agricultural and spiritual practices.

The Hopi Tribe live on their ancestral land, now a sovereign nation comprised of three mesas with 12 communities that overlook windswept rocks into the vast arid vistas of the plains. In spite of the elevation, low precipitation, drying winds, and short growing season, for centuries the Hopi have been successfully farming the land below their ancient villages, without irrigation. Many of the corn fields are small and still planted by hand in pretty much the same way their ancestors have done it for thousands of years. The lifestyle is hard, but one that is chosen because it enables them to be close to the land and its spirits. The Hopi are renowned for their traditional dry land farming with their primary crop being corn, along with squash, beans and melons. Corn is an important symbol of the Hopi and two stalks of corn appear on the Hopi flag symbolizing a life in balance with creation.

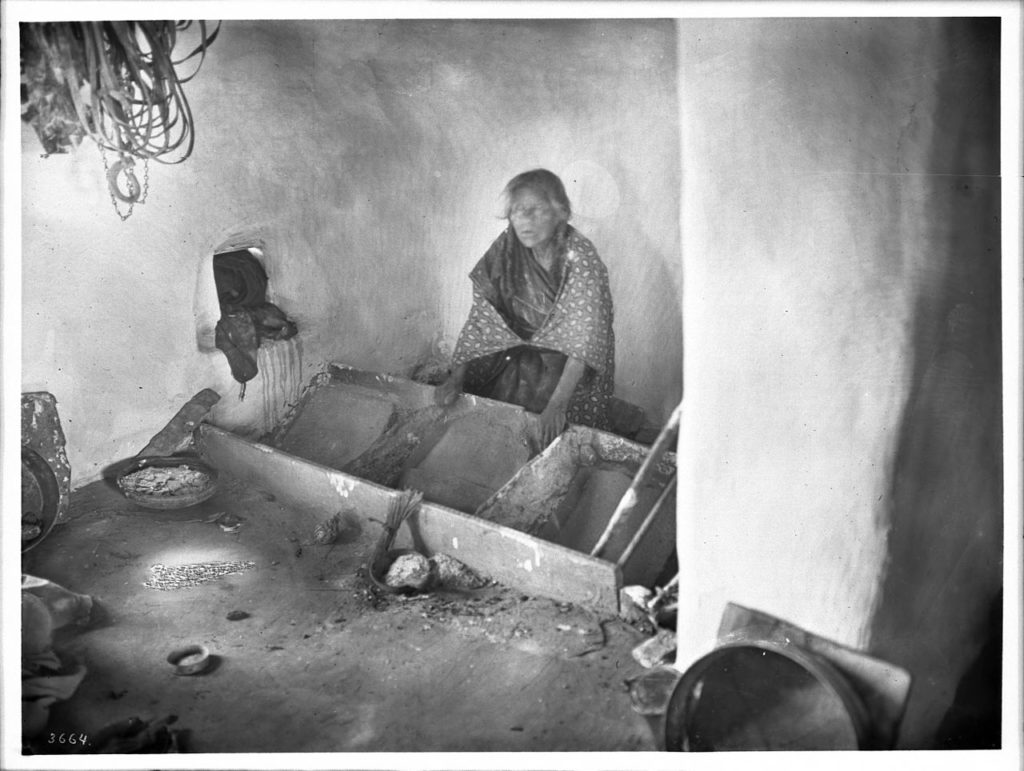

Hopi society is matrilineal. The women not only pick the leaders because they have known them since babies, they are the protectors of the seeds. Seeds are sacred and seed keepers must protect the seeds and related ceremonies. They are responsible for ensuring that there is corn for food and ceremonial uses and enough seed stored for four years. The corn fields too belong to the women and they sort and protect the yield. Men work the corn fields, planting with a tool called a Hopi planting stick, a flat headed digging stick which allows them to create a foot deep hole into which they sow multiple seeds, so they can find moisture. These seeds have been carefully adapted over time to high and dry elevations of what is now northeastern Arizona.

When these seeds germinate, a central root is encouraged to go deeper in search of water, aided by the rhythms of ceremonial drumming, rattles, dancing, and singing above ground. These traditional tribal songscapes are performed with precise vocalizations using repeated phrases in Hopi, an Uto-Aztecan language. These songs are said to be ancient and to have passed unchanged from one generation to the next. Thomas explained that the Hopi Way was to help the plants and Mother Earth through sacred rituals, prayers, and ceremonies. He said that the Hopi’s traditional melodic and pulsating music originated from the creator—the Great Spirit— Màasaw.

Ancient wisdom has played a constant and vitally interwoven role in Hopi agriculture. Hopi people know that their land is connected to the forces of nature. All living things, especially corn, must be nourished with prayers for rain and blessings through song and dance, in a way that can be heard heard by spirits.

How these cycles of seasonal ceremonies create harmony with Mother Earth may seem a sort of supernatural metaphysical mystery but that could not be further from the truth. There is a growing body of remarkable research and exciting ‘discoveries’ supporting the positive effect that music, as a blend of harmonious frequencies and vibrations, has not just on humans and animals, but also on plants that react to sound vibrations even at the seed stage. In fact, exposure to certain musical frequencies may be essential in some circumstances, changing plant metabolism, and improving growth and yield.

A study published in The International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences found that music not only accelerates growth of plants but also significantly influences the concentration of various metabolites. Research published in the International Journal of Agriculture and Plant Science found that music not only increased oxygen uptake, “the frequencies in these vibrations facilitate the physiological processes like nutrient absorption, photosynthesis, protein synthesis and an overall development of healthier plants with better yield.” Additionally, this study looked at the positive effect of religious chanting on plant growth.

Thomas spoke of the spiritual importance of farming to overcoming the challenges of the conditions through a spiritual connection, communicating with the plants, such as their sacred blue corn, and environment in a way to increase their resilience. My discussion with Thomas foreshadowed the growing effects of climate change, revealing how the Hopi have cultivated resiliency practices for hundreds of years, practices which are considered novel climate adaptation techniques today. Not only is understanding their techniques of dry farming important for climate change, but understanding how acoustic treatments can enhance drought tolerance for plants can be a needed tool against the forces of global warming.

Thomas says, “White people finally discovered that when you play music for a plant or sing a song or something, pray for it, it grows very good. And we knew that a long time ago.

There are forces required underneath that are helping to keep this land in balance. So that’s why when you ask many native people they don’t know why when we are dancing we stamp our feet. When we do that we let underground forces, spirit people know that we’re still carrying on the ceremonies.”

If you want to know how to grow corn in a warming world, talk to the Hopi. They have grown corn in an arid climate with little water for centuries, and over time have cultivated drought tolerant corn varieties. But even the Hopi, maybe the world’s best dry-land farmers, are having some difficulty as the scorching heat and drought increases.

We all have the ability to synchronize our minds with the frequencies of the living world. Life is sacred, with sensorial dimensions and connections that are sometimes beyond our immediate understandings. We must find a way of relating to the earth as a living organism and understand the inherent interconnected and interdependent natures of ecosystems.

If you’d like to listen in on my 1989 visit to Hopi, view the film Thomas Banyacya: The Hopi Prophecy, which documents a circle gathering of Thomas Banyacya, Hopi high religious leaders, and visiting Lummi, Lacandone, American, and Mexican environmentalists. The film went on to screen at the United Nations Environmental Programme, at the request of the Hopi elders of Hotevilla, and was broadcast on PBS.

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D. is the creator of World Sensorium and founder of the World Sensorium/Conservancy.

Braam J, and Davis, R.W., 1990. Rain-, wind-, and touch-induced expression of calmodulin and calmodulin-related genes in Arabidopsis. Cell. 60(3):357-64. DOI: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90587-5. PMID: 2302732.

Chandrakala, Y. & Trivedi, L., 2019. Role of music on seed germination: A mini review. International Journal of Agriculture and Plant Science, 1(2), pp.1–3.

Ramekar, U. V. and Gurjar, A. A., 2016. Emperical study for effect of music on plant growth. 10th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Control (ISCO). 1-4. DOI: 10.1109/ISCO.2016.7727025.

D. Sharma, U. Gupta, A. J. Fernandes, A. Mankad, H. A. Solanki, “The effect of music physico-chemical parameters of selected plants”, Int. J. of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences, vol. 5(1), pp 282– 287, 2015.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.