Energy is a Form Giver

A Conversation with R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA

By Liz Macklin

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

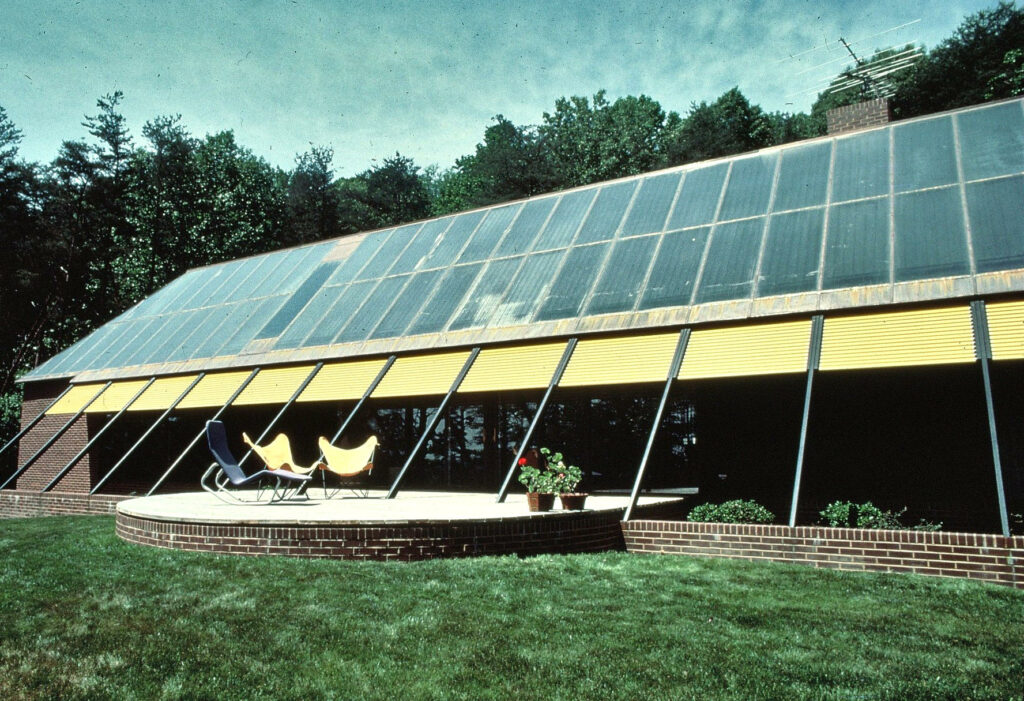

Sited on a hillside with a long row of windows set precisely to let in sunlight, the house impressed visitors with the most up-to-date technology of the late 1970s. Adjustable solar shades blocked the sun in summer and on cold days an array of solar panels supplied heat. Owner and architect R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA, understood the opportunities in energy-conscious design.

Over the next two decades he championed the design of buildings adapted to the climate and resources of the region in which they were built. As a co-founder of VVKR with his brother, architect William Vosbeck, FAIA, he led the firm’s architects and engineers in designing energy-saving systems for buildings in the mid-Atlantic region. He described their approach saying, “orientation, siting, materials, daylighting, natural ventilation, thermal mass along with efficient electrical and mechanical equipment [and] economizer cycles … were all important factors the design teams considered.”

In 1981 he envisioned a movement with architects taking the lead in planning for energy conservation, and as president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), he chose the theme “A Line on Design and Energy.” He supported Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) in discussions with members of Congress, and while on the Council of the International Union of Architects, he wrote, spoke and advised architects worldwide.

Given his extensive experience and the perspective of his 92 years, I wondered how he would view our current progress. He answered my request to reflect on the status of design, energy efficiency and sustainability in today’s world.

Early in your career you emphasized the important role architects had in energy conservation in the built environment. In this period of climate change, minimizing a building’s energy footprint has never been more important. What do you think architects can do today to help preserve the environment?

It’s been well documented that the built environment is now producing close to 40 percent of the total greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, released to the atmosphere. This can be attributed to carbon produced by buildings during construction, as well as by heating, cooling, lighting and other sources after they are built. So, the design of new buildings along with the renovation of existing buildings to reduce greenhouse gases is vital to making our world more healthy and resilient in the future. Architects must be ever aware of the best design practices to mitigate the carbon footprint of the buildings they design.

I’m aware that the American Institute of Architects (AIA) is promoting this emphasis in a number of ways. They are encouraging firms to design toward net zero emissions, which means achieving an equal balance between greenhouse gases released and those removed. That is a phrase you see a lot now in the AIA material: net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by employing energy efficient measures and by utilizing low impact building materials. The AIA also urges architects to encourage renovation of existing buildings with energy conserving measures, something which is too often neglected. The AIA continually offers education for architects on net zero design and energy efficient modeling.

Architects have an essential role in designing built environments that are sustainable and use energy as a form giver. I recall that phrase from many years ago during my AIA presidency. I used to say that energy is a form giver, and with that I was stressing regionalism in architecture. When an architect uses energy conscious design techniques in a particular region, the process and materials will have an impact on the form of the architecture that is created.

It’s interesting that you say regionalism is something to consider.

Yes, that has often been overlooked. For many years the same building in New York could be found in San Antonio. Now in its Framework for Design Excellence, the AIA offers guidelines with examples of outstanding regional design in buildings throughout the United States.*

What about green building materials? Have you seen any that could change building design?

I’m sure there are many. As I’m no longer in practice or even consulting, I hesitate to mention specific materials. However, I do see more and more high performance low-e (low emissivity) glass being utilized and it is manufactured with coatings to control heat loss or gain, as well as the transmission of infrared and ultraviolet rays. You know that glass has always been a part of modern contemporary architecture and in my era if you got double-paned glass, it would be good. Now there is exceptionally high-performance glass and it’s here to stay.

And that will allow for more natural light and views to the outdoors. How about other ways the built environment can renew and strengthen connections between people and nature? You have begun to talk about that. Do you have other thoughts?

Yes, I do have some general thoughts on that subject. The population of the world keeps growing and, unfortunately, putting more stress on our natural resources. Growth is inevitable, but it must be managed. It takes some doing. There has to be more attention on how built environments, along with important lifestyle changes, dramatically adjust to provide more sustainable environments. There are a lot of factors, particularly here in the west where decreasing water supplies have become a huge issue. With drought areas ever increasing, availability of water has an impact on where you can have growth and how it must progress.

Our forests and natural spaces are diminishing. The infrastructures for vehicles, and by that I mean paving, parking lots, garages and other impervious types of structures, are taking up an increasing amount of real estate. Also, superhighways continue to be built and more lanes are being added to highways like those between Denver and the mountains. The expansion of impervious pavement and structures is fragmenting and damaging our natural resources.

I read a report recently that two-thirds of the world’s glaciers are now on track to disappear by 2100. That is still more than 70 years away and I don’t have a solution, but we certainly need more attention to dealing with climate change. Climate issues coupled with population growth are creating massive challenges for planners. I fear our government agencies, land planners, developers and architects are not sufficiently addressing these issues and must give more attention to the preservation and revitalization of nature.

Are you saying it takes a community effort – that it can’t just be government or corporations or individual citizens — everybody has to look at what they have power over and work toward a solution?

Yes, absolutely. Government agencies usually have the right intentions, but in the public sphere there is pressure from developers, land planners, architects and many other groups. The point that everyone has to cooperate and participate is an excellent one. We know there are climate change naysayers, including many who passionately feel we are just in a cycle of warming and cooling that the world has experienced for centuries. But hopefully, even if they continue in that belief, they will ultimately recognize the social, economic, and health improvements that will result from a built environment that addresses climate changes, no matter what its cause.

Do you have any thoughts about density, whether we should make our cities even more dense to allow our agricultural and forest areas to remain, so that development doesn’t encroach into them? It’s not an easily solved issue.

No, it’s not, but we have to try to increase density – not just in the big cities but in suburban areas as well. Most people like their individual residence and green yard around it, but if you look at some of the older cities in Europe the densities are high compared to the density of most of our cities and suburbs. It will be a hard sell for the US, but it needs to happen, sooner rather than later.

Then back to the traffic issue. We’ve got to have more and more rapid transit. I know people still like to have a private vehicle, but in the long run, if you think about the train system in Europe, people ride trains everywhere. In this country not so much. We use cars and trucks and buses, but the more impervious areas we have, the less green space there will be. Transportation systems have a long way to go to address this impact on nature.

I want to ask one last question on a lighter note. Do you have a memory of an aroma associated with a plant or landscape that you’d choose to share?

I have a memory that might relate to this, not exactly an aroma but a strong sensation. To me there is nothing like getting off of a ski lift or gondola at an elevation of about 10,000 or 11,000 feet with a beautiful clear blue sky and crisp air and looking around at the landscape of snow and mountains and pines and aspens. It’s a memory that I cherish — just thinking about how I used to ride the chairs and ski on those blue-sky days. When you’re up at 11,000 feet the sky is even bluer.

Now with rising temperatures I fear experiences like this are fading away for future generations. Let’s hope not—but the world must act now to protect these resources.

His image of mountain skies and the slopes covered in snow – now in absolute peril—captured my attention and stayed with me. As a pioneer of energy conservation and sustainable design, he offered the possibility of an alternative, but the necessary steps are up to us. We must work together and adapt, if we want to preserve our abundant and awe-inspiring world.

*You can learn more about the American Institute of Architect’s Framework for Design Excellence Program at their website:

https://www.aia.org/resources/6077668-framework-for-design-excellence

For information from the UN Environment Programme’s COP27, 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction, which found that the sector accounted for over 34 per cent of energy demand and around 37 per cent of energy and process-related CO2 emissions in 2021, see their website:

Liz Macklin teaches in the educational outreach programs of the Virginia Master Naturalists and has worked as an architect, artist and writer.

Plantings

Ecological Kinship Makes Scents

By Jake Eshelman

Edwina von Gal on Ecological Action and Habitat Restoration

By Gayil Nalls

How Does Your Garden Grow?

A Conversation with Vivian Berry, Cultivator and Steward of Berry FarmZ

By Véronique Firkusny

Samuel Morse

Locust Grove Estate and Nature Preserve

By Gayil Nalls

The Power of Weeds to End Hunger in an Uncertain Climate

By Lewis Ziska

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Basmati Rice with Pumpkin, Asparagus, Cauliflower and Grana Padano ‘Waffle’

By Chef Giovanni Parlati

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.