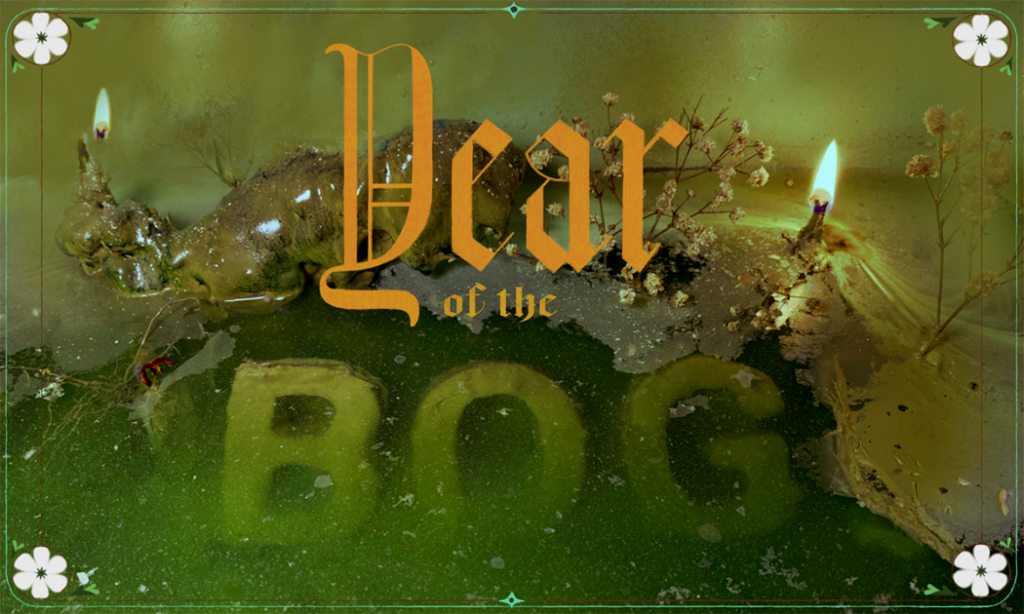

Swamp installation by Yoav Admoni. Photo by Eric Tschernow.

Berlin’s Bog as Metaphor—or Why We All Live in the Bog

Interview with Frances Breden

By Braden R. Bjella

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

The work of Coven Berlin is difficult to characterize. While the group tends to explore themes like sexuality, love, feminism, gender, politics, capitalism, and the interplay between all of the above, the actual mechanisms it uses to do so can vary incredibly. Sometimes, the group’s work takes the form of a walking tour through an imagined history of Berlin; other times, it recasts Internet memes as both art and a marker of shared cultural understanding, allowing viewers to understand their place in contemporary expression.

For 2020’s Burlungis, however, Coven Berlin opted to share its ideas by bringing observers into a metaphorical—and literal—bog. The show, housed in Berlin’s Galerie in Turm complete with a constructed bog, explored the often untold queer history of the Middle Ages among other themes. Over the course of the exhibition, viewers began to understand the bog as a metaphor—a queer, slow-moving ecosystem that both filtered the world around it and came to represent everything that passed through it. Eventually, the success of this exhibition and desire to explore these ideas further led to the YEAR OF THE BOG—a largely cyber piece that tried to connect people to the world around them at a time when they were stuck inside their homes owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Frances Breden of the group discusses Coven Berlin’s connection to the bog and what can be learned from these queer ecosystems.

What drew you and Coven Berlin to bogs specifically?

Our first bog piece, Burlungis, started when Coven did a residency at Rupert in Lithuania. We did a walking tour of a bog, and the guide explained how this bog was related to Lithuanian folklore, and that so much of the local folklore was related to the actual nature and geology of the place. At that same time, we were reminded about how Berlin was also founded on a bog—there used to be this big bog stretching basically across Europe from the Berlin area eastwards.

For Burlungis, then, the bog became a metaphor. With the rise of capitalism and extractivism in Europe after the Middle Ages, it was really important for people in that time to make the Medieval period seem really bad and dirty—like something we needed to move away from for the sake of progress. That time also saw collective land ownership disappear: swamps and bogs were drained, usually to make way for new development. We became interested in taking a queerer look at that time, looking at how the Middle Ages are represented today, how that imagery is used, and what stories we tell about the Middle Ages.

We had a lot of fun with that, and then COVID hit. We had another theme for a bit called In Heat, but I think we knew we weren’t done with the bog. With everyone in lockdown, we wanted to do something that people could really feel like they could touch—something physical and organic, something that made you think about being outside and the land under your feet.

This brought us back to the bog, because bogs are a community. Many people have written about how bogs are queer ecosystems, because they’re often overlooked, not super normative, and don’t really fit our idea of a generative capitalist body. They’re not very fertile places. Here the bog became a metaphor again, this time for the Internet. We started thinking about how we relate to each other online—not in a corporate, advertiser-friendly way, but in a weird, difficult-to-understand, kind of fucked up way. There’s always something weird bubbling up from under the surface online. The Internet, like the bog, has an odd scale of time. Especially being stuck inside and spending more time on the Internet, we came to the understanding that we are all living within this bog, which has both benefits and, much like the bogs of nature, risks stemming from development and capitalism.

Both as metaphor and as literal bogs, are bogs ugly places? And how does that feeling influence how we view them?

I do think the bog is ugly, or can be. I think that was also part of our exploration of the bog. There’s this idea that, you know, it’s a lot easier for environmentalists to get people to identify with something like ‘save the whales’ rather than something like ‘save the slugs.’ In the end, how you relate to it comes down to something kind of like empathy.

We’ve written about this, but humans are not really drawn to most things in nature super affectionately. So, we chose to present the bog and really think about it in a different way. Even returning to that crude capitalist logic, it’s pretty interesting that, for a long time, people didn’t see bogs as productive because you can’t really grow produce there. But now, there’s a lot more science coming out that shows how they’re great carbon sinks, they filter out toxins in rivers, and more. Of course, this was indigenous knowledge for ages; there’s a reason that indigineous people didn’t destroy the bogs. Again, the bog is this strange, maybe ugly but also unique that is so easily overlooked or misrepresented.

Much of Coven’s work is made and presented in cities—can you talk a bit about that, given how your work often relates to nature?

Yeah. For us, it’s a bit tired at this point, but there’s this thing about how the name ‘Berlin’ might originate from a proto-Slavic word meaning ‘swamp.’ For a long time, however, people instead had this narrative that it came from the word for ‘bear’ because they want it to be Germanic—and because ‘bear’ just sounds so much cooler.

That idea, though, shares our theme of recognizing that we are all in this ecosystem. The divide between nature and city is a construction. It’s not real. Why is the wetland the middle of Berlin—the one that extends almost all the way underneath the city—less ‘natural’ than a wetland in the ‘wilderness’? That was part of what we were saying with Burlungis. The bogs and swamps that ‘used to’ be here are still just below the surface of the city. That’s why it’s so hard to build here. And, probably, they will come back at some point. This city will not last forever, and the bogs will come back.

This is a bit more abstract, but what do you as artists and thinkers gain from engaging with nature in this way?

You know, I don’t know. That’s something we want to, and plan to, explore more in the future. We really came to the bog understanding that it could be a metaphor, as a massive and important thing that we don’t fully understand. We’re definitely not trying to pretend that we are environmental scientists or people who live super ‘in touch’ with the land. It’s a step or a gesture toward that, definitely, but we’re not trying to get all pseudo-scientific… There’s a big thing in the art world right now, which is the idea of slowing down. Bogs operate on a really extended timeline; they do a lot of preservation and archiving. That’s also part of this whole Internet metaphor—it just holds onto things for so long, and things come up when you don’t expect them. That idea has been important for us. Bogs have come to hold all kinds of strange life in a specific, weird ecosystem, in a way sort of fighting the idea of hyper-productivity. And in the end, the bog is just a nice place to hang out.

Frances Breden is a curator, project coordinator, and one sixth of the queer feminist art collective COVEN BERLIN (covenberlin.com), with whom she’s worked since 2014. Frances is a founding member of Sickness Affinity Group (sicknessaffinity.org), a collective offering support around topics of accessibility, disability, and illness.

Braden Bjella is an American culture journalist based in Eastern Europe covering music, politics, history, the environment, and the intersections therein.

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.