Reef Point,” Beatrix Farrand house, Bar Harbor, Maine. Pathway to house.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

For a decade, from 1946—1958, Beatrix Farrand (1872-1959) wrote and published the Reef Point Gardens Bulletin, from her house and garden in Bar Harbor, Maine. Mrs. Farrand, the niece of the author Edith Wharton, was by then, one of America’s preeminent landscape architects. Her career included design commissions from many famous residences, parks and botanic gardens, including Dumbarton Oaks and The White House. The bulletin documented the house and garden design and its maintenance—but most importantly–environmentally sound gardening practices, championing perennial and native plants, making her work very important to modern gardeners and todays stewards of the land.

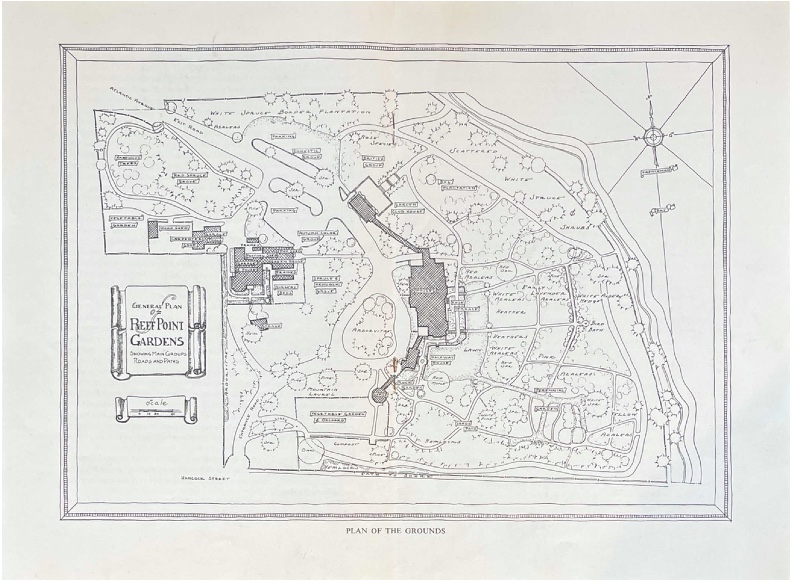

The Plan of the Grounds

By Beatrix Farrand

Excepted from the Reef Point Gardens Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 3, September, 1948

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

Although the present six acre unit of Red Point Gardens has been gradually assembled from three different lots, all seem to fit into the same pattern. The land is shaped rather like a clumsily made mitten without a thumb; the eastern side at the top of the mitten is bounded by the sea, cottage lots adjoin the area to the north and south, and beyond the gates at the ends of Hancock Street and Atlantic Avenue the last housesb stand near the western boundary.

The six acres slop upward from east to west, the contours roughly following the shape of the mitten; ridges of rock lie near the surface everywhere except where an old glacial brook course runs northeasterly into a cove. This small ice-gouged pocket is deep and beneath it lies a bed of glacial clay covered by layer of poorly drained mucky soil where bog plants thrive. There are deposits of old silver sea sand near the shore, hidden here and there by a thin coat of blackish peat, a condition much to the liking of the heath family. As the land rises toward the west the soil coat is thinner but is nevertheless deep enough to allow large trees to grow, and throughout the acreage drainage is perfect, sometimes rather too good, except in the little boggy pocket.

The central lot was bought first and a rocky ledge about midway between the sea and western boundry chosen for the house site; its placing was as inevitable as the plan for the grounds, since landscape design must be controlled by topography. A drive from the foot of Hancock Street was placed on the extreme southwest corner, because the middle lot could only be reached by a right of way across the western end of the adjoining one. The house was built in 1883, and at that time a stable seemed as necessary as a garge today; therefore a spur road led to a small building in the northwest corner of the property where the gardener’s new house now stands. The drive had to be built on easy curves as the old four-seated buckboard required as much elbow-room as the longest modern motor car; this was fortunate because the old oval opposite the front door is large enough for present needs. Soon after the house was built a friendly but unpleasantly far-sighted visitor inquired where the boundary lay; when shown a near-by tree marking the southern line he innocently asked what would happen if a new house should be built almost within arm’s length. After then underlying significance of this chance remark had been assimilated there could be no ease of mind until the southerly two acres were added.

Most of the near-by seaside properties had already been cleared of native shrubs and ground cover in order to make smooth and level lawns. The owners of Reef Point were interested in native plants and welcomed the protection given by trees and shrubs, and finally, neither wished to haul the large amount of loam in order to make a lawn nor give it the constant after care. So the natural growth was fostered and footpaths following the land contours seemed to place themselves naturally, and little by little the various sections showed the way for later development. A walk from the house to the shore was as much needed as a road approach; then a second path toward the sea started the present pattern radiating from the southend of the house. These footpaths were crossed by others meant primarily for care and weeding of the plantations. Asmall undersized tennis ground at a little distance from the house gave lively pleasure in the early days, but as energies veered from tennis to gardening the court because a garden of perennials and annuals.

certain plants would gladly grow where conditions were what they had silently and persistently demanded

During the first years leaves and pine needles were vigorously raked off each spring and autumn, but the owners at last realized they were fighting their own gardening plans by sweeping away what nature was patiently trying to make into good soil. Since the lesson was learned more than forty years ago leaves and small waste have been saved, whether lying on the ground under the pine and spruce trees and fern beds, or carefully gathered and later returned to the land. The gradual accumulation of topsoil has had a marked effect on the design of formerly starved regions now nourished healthy plants. Certain areas were classed as “difficult children,” since they refused to grow anything except a meagre crop of spindly trees and dilapidated juniper bushes. The present vegetable garden was one of these problem children, but it was soon realized that shelter from wind was as urgently needed as topsoil, therefore the kitchen garden was given the first protection. A carefully designed high wooden fence was completely successful and before long dwarf fruit trees throve among the vegetables. Outside the fence tall trees were encouraged to grow on the north to give additional windbreak, and higher temperatures inside the enclosure proved the usefulness of the protection.

“Reef Point,” Beatrix Jones Farrand house, Bar Harbor, Maine. Fieldstone pathway to bench. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

In the early days visitors to Reef Point were puzzled by the lack of a trim lawn stretching unbroken to the sea. Occasional delicately veiled remarks indicated a question as to whether the dominant trees and shrubs implied a spirit of economy, while others asked more openly why the type of plantings had been chosen. As the years passed the owners learned to understand the conditions more intelligently and instead of forcing an unwilling site to resign itself to something for which it had no liking they studied the area and found out by many trials and frequent errors that certain plants would gladly grow where conditions were what they had silently and persistently demanded. Careful observation showed that azaleas liked the moisture from the sea and old silver sand under their feet: they were further aided by the wind buffer of the surrounding fence. Slowly and largely by rule of the gardener’s green thumb many plants which had been sulky are now happily established on formerly unpropitious sites.

Fortunately there is variety of aspect and soil; in some places full sun, in others deep evergreen shade or dappled shadow under deciduous trees, and here and there sandy and peaty soil with occasional pockets of blue clay laying under gravelly slopes.

A small lawn finishes the setting of the main building below the little layers of terraces, and beyond the grassy space lie the larger groups–heathers in bright sunshine and sandy soil; ferns in a damper hollow, and groups of azaleas near the sea with other native and alien plants.

When the idea for a permanent future for Reef Point began to develop in the minds of Max and Beatrix Farrand they realized that if any considerable number of visitors were to be welcomed to the garden there must be easier access than provided by the original entrance drive and circle near the house; therefore when two acres to the north were added to the four at the south the design began to evolve. First the old driveway was altered in line and widened to ensure safe passing of vehicles; but it was kept as the main entrance since it allowed a convenient right-hand approach to both house and garden paths. Then on the northern acres a new road was constructed as an exit, and two spaces made for cars of visitors and guests. The new lot had long been neglected and the soil denied all nourishment; however, a small groupof red spruce trees near the northern gate survived and the grove has been kept as an object lesson of the foetitude of native trees under adverse conditions.

“Reef Point,” Beatrix Jones Farrand house, Bar Harbor, Maine. Fieldstone pathway to bench. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

When the house was built it was perched on top of a ledge sloping sharply eastward towards the sea; the front door on the southwest was reached on a level but the whole east side of the house looked perilously suspended in air as it was supported by piers connected by flimsy latticework. Shrubs and sundry other attempts to disguise the awkward change in level between the east and west sides of the building were not convincing; so finally the decision was made to build several small terraces following the varying grades as they increased in steepness on the sea side. Few notice today that the ground falls quite abruptly from the near-by street to the house site, and fewer still realize that the tops of the house chimneys are approximately level with the principal village street.

A professional workroom separate and yet connected to the dewelling by a passageway was clearly needed as the house was often littered with plans, catalogues and seed lists, accordingly, when material was available for its construction an office was built a short distance frim the main building. A ground floor room was arranged for a secretary and the upper story made into a study, quiet, remote, yet conveniently near. On the north side of the the house another passageway leads to a second garden house and gives access to the northern spaces, thus linking the main building to the two garden houses, the office and the parking ground. Physical conditions dominate the lines of the plan; the arc of buildings from north to south follows the curve of the sea front at the finger tips of the mitten. The shore path, open to the public, the near-by streets, and the neighboring houses are also controlling elements in the design.

The development of the western part of the acreage has come naturally because it was cut by entrances and paths; in one sense it is the least horticulturally important since considerable space had to be allotted to necessary working units, such as vegetable garden, roads and parking spaces, the gardener’s house and adjacent toolhouses and greenhouse, fertilizer sheds, cold frames, and a small cutting garden.

Two or three paths lead to the garden, one in the deep shade of pine and spruce trees where acid soil loving plants are happy in the poft moist leaf mould under the evergreens; Christmas ferns, dog-tooth violets, goldthread, trilliums, and gingers seed themselves and spread happily.

The most interesting plant groups lie on footpaths between the house and the shore. All are surrounded by a truck service road which follows the south, east and north boundaries. This road gives necessary and easy access to the various plantations and peat, compost, plants, gravel or stone are taken close to where they are needed. When this road was first discussed all agreed in thinking it wasprobably an extravagance and likely to be of little use, but to everyone’s surprise it has developed into an essential artery and hardly a day passes without proving its usefulness.

The terrace shelves near the main building carry the most intimate and detailed planting. The earlist bulbs and latest flowers are here and from mid-March until November there is colour, whether timidly appearing in earliest spring or gallantly withstanding the autumn frosts. An easterly terrace is planted with single roses where they enjoy morning sun and are shielded from hot southwest winds and afternoon heat. A small lawn finishes the setting of the main building below the little layers of terraces, and beyond the grassy space lie the larger groups–heathers in bright sunshine and sandy soil; ferns in a damper hollow, and groups of azaleas near the sea with other native and alien plants.

Years of close observation have shown that certain shrubs are contented in special positions– for example, groups of rhododendrons were set out where they are shaded from the low winter sun, and in another place dwarf deciduous and evergreen azaleas thrive in a situation akin to their native birch groves on Tibetan highlands.

The flower fgarden lies behind a screen of trees, partly hidden and wholly protected. Theborders are planted with perennials chosen not merely for attractiveness of flowers but for character and beauty of growth and foliage. The plants are expected to be at least presentable when out of bloom and annuals are added here and there only to replace early sorts while later ones develop. A second path passes through a carpet of bunchberry, and a third in full sun crosses the heathers. The soil is gravelly to the north of the house; therefore several experiments have failed, but a group of the low-pasture juniper combined with the seaside species gives promise of good behaviour.

Years of close observation have shown that certain shrubs are contented in special positions– for example, groups of rhododendrons were set out where they are shaded from the low winter sun, and in another place dwarf deciduous and evergreen azaleas thrive in a situation akin to their native birch groves on Tibetan highlands.

Reef Point has been a part of its village for over sixty years and this close fellowship is valued; it wants to help local and visiting horticulturists who take an interest in their gardens and to welcome all who care for plants, birds and out-of-door beauty. In this way it hopes to take its place in the community and state. Those who are working at Reef Point will do their utmost to help Bar Harbor welcome visitors and friends as a mark of gratitude for preservation from destruction by the fires of last October.

Beatrix Farrand

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.