The “Three Wise Men.” Detail from a mosaic in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy, “Mary and Child, surrounded by angels”, completed within 526 AD by the so-called “Master of Sant’Apollinare.”Nina-no CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia

Embodying Heaven: Frankincense and Myrrh and Their Connection to Divinity

By Nuri McBride

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

In Matthew’s account of the Birth of Jesus, three wise men, drawn by a star, came from the east to find a newborn messiah. They brought gifts for the child befitting a king: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. These exalted gifts have often been the butt of contemporary jokes, ‘the gold is nice, but who cares about frankincense and myrrh?’. This attitude, however, fundamentally misunderstands the role aromatics played in the Eastern Mediterranean during antiquity. Gold might make you rich, but the plant aromatics of frankincense and myrrh made you divine.

However, one should not make the mistake of assuming that aromatics used in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean were merely a matter of aesthetics or metaphor. Aromatics, primarily from plants, instead, were part of an embodied worldview. Olfaction was a sensorial path to knowledge, wholly divorced from the sensory hierarchy that would develop in later Hellenistic thought.

The pre-Modern nose marked time- with scent;

delineated sacred space- with scent;

communicated with their gods- through scent;

and believed truth could be known- through scent.

Evil and holiness were understood by how they smelt.

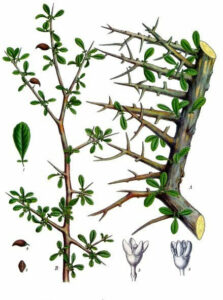

Frankincense, an aromatic resin obtained from Boswellia trees and myrrh, from the Arabian tree known as Balsamodendron myrrh, were aromatics deeply connected to divine communication long before Jesus was born. They were essential for the daily offerings at the Temple in Jerusalem, which God perceived through divine olfaction. Sacrifices were accepted if they had ‘an aroma pleasing to the LORD’. They were employed in the worship of the gods of Egypt for nearly 4,000 years. Frankincense and myrrh were the ‘sweat of the gods’, a physical manifestation of holiness. The Egyptian word for frankincense is senetjer, deriving from seneteri– to make divine.

As time passed and the seat of Christian thought shifted from the Eastern Mediterranean to Western Europe, the olfactive culture of Christianity changed as well. Despite that, vestiges of this older embodied tradition persisted in European Christianity, partly through the redolent spiritual phenomena of Myroblytism & Osmogenesia. The odour of frankincense and myrrh once again represented embodied truth and heavenly connection. We will explore two examples of this through St Nicolas and St Polycarp.

Saint Nicholas-The Myrrh Gushing Saint

The Santa Claus of popular imagination is based on St Nicholas, the 3rd century Bishop of Myra. Little is known about Nicholas’s life except that he attended the Council of Nicaea, signed the Nicene Creed, and supported the Trinitarian doctrine. Everything else comes from legends that may contain kernels of truth but have been heavily folklorised. For instance, almost every myth associated with St Nicolas involves the number three, perhaps in deference to his feelings on the trinity.

Myroblytism is the act of a supernatural aromatic liquid called myroblysia (sometimes referred to as Manna), exuding from the relics or burial place of a saint, with no know natural explanation. The Eastern Orthodox Church will also accept Myroblytism from icons or statuary. A whole category of saints is known as the Myroblyte (myrrh-gushing) saints.

Myron, the root word of Myroblytism, is the Koine Greek word for myrrh oil that would develop into the general term for perfumes in antiquity. However, myron remains closely associated with myrrh-infused oil in the Christian context. Chrism, Christian anointing oil, is based on the Shemen Ha-Mishchah of the Jewish Temple. The formula for this oil is found in Exodus 30 and primarily consists of myrrh-infused olive oil. Myroblysia is clearly meant to invoke otherworldly Chrism in the narratives surrounding the Myroblyte saints.

St Nicholas’s wonderous body has gone on quite an adventure since his death in 343 CE. He was initially entombed on the small island of Gemile. However, we have no documentation of his remains producing miraculous myron on the island. Nicholas’s Myroblytism began in the mid-600s when conflicts in the region left Gemile vulnerable to attack, and Nicholas’s remains were returned to Myra. It was in Myra that the remains allegedly began to produce myroblysia. In the oldest accounts, his myroblysia was said to smell like rosewater.

However, in 1087 CE, a group of Italian sailors ransacked St Nicholas’s church and smashed open his sarcophagus. They stole Nicholas’s skull and long bones. Those remains would end up in Bari, Italy, at the Basilica di San Nicola. Later in 1100 CE, Venetian crusaders took his remaining small bones and fragments to be housed at San Nicolò al Lido in Venice.

The Venetian remains never produced myroblysia and did not become a significant pilgrimage site. However, the bones in Bari did; only the odour changed in Italy. There, Nicholas’s bones produced an oily substance smelling like sweet myrrh. Nicholas’s myroblysia is still collected from his tomb in Bari on his feast day (December 6th). It is easy to write this all off as hokum from a superstitious age. The exact origin of the oil poured into St Nicholas bottles is inconsequential to the spiritual importance of Myroblytism to the sensoriality of the Christian mythos.

The presence of myroblysia served as sensorial validation to the faithful that miraculous intervention was possible. It was something people could see, touch, smell, and taste, which challenged the regular course of nature. It left open space for the divine and knowledge beyond reason. Myrrh-gushing is part of this embodied experience where one’s spiritual acts manifest in one’s body. In this, the state of the body can show proof of the disposition of the soul and indicate a connection to God. Because of these bones’ direct connection with the early Eastern Church, we see manifestations of this embodied religious experience surviving into his modern Western veneration.

The Fragrant Sacrifice of Saint Polycarp

The Odour of Sanctity, formally known as Osmogenesia, is a supernaturally pleasant odour, with no earthly origins, coming from the dead body of a saintly person. The fragrance emerges either during or after death. It has no physical component as myroblysia does. The scent could be brief or persistent, attached to the body, grave, site of martyrdom, or objects the person touched. While nearly any odour could be classified as Osmogenesia, odours of religious significance are most frequently cited, specifically rose, lily, frankincense, and myrrh.

The odour’s presence was a physical sign of a spiritual state of perfection that could defy the carnal scents of death. The concept rose to popularity in Europe in the early Middle Ages with roots in the early Christian communities of Greece and Egypt. In fact, Wise argues that the Coptic manifestation of the Odour of Sanctity developed out of the remains of pagan Egyptian incense worship1.

Modern theologians will say that the Odour of Sanctity is metaphorical and an ontological state of being. While that may be true now, or for religious scholars of the past, it was indeed understood and preached as a literal odour to the laity. Osmogenesia was born from the older embodied tradition of early Eastern Christianity. Yet it resonated with the Medieval and Early Modern European laity, who had their own embodied knowledge systems disrupted by the expansion of Christianity into the West. One of the earliest incense saints to have his mythical fragrance preserved in Western hagiography was St. Polycarp.

St. Polycarp, the 2nd century Bishop of Smyrna, was martyred by burning at the stake. In his hagiography, the flames domed around his body, baking him like bread instead of charring his flesh. From his pyre, the smell of frankincense and myrrh emerged and overwhelmed the onlookers.

Polycarp’s martyrdom was sensorially connected to the Temple’s incense offering and the gifts of the Magi through frankincense and myrrh. The odours used were intentional and conveyed information about the religious significance of Polycarp’s death. As incense was burnt in sacrifice to God at the Temple, so too was Polycarp burnt. Polycarp’s refusal to preserve his life wasn’t suicidal; instead, it was a willing sacrifice to God. The supernatural appearance of frankincense and myrrh become evidence of God’s approval and acceptance of the act as ‘an aroma pleasing to the LORD’.

Nativity, Temple & Embodied Mythos

In both Nicholas and Polycarp’s stories, the use of frankincense and myrrh connects the circumstances of their death to the olfactive manifestations of Jesus’s divinity. The gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh by the Magi should be understood as offerings to a god-king. After all, the Magi say to Herod, ‘We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.’

The Greek word used is proskyneō (προσκυνέω)- to prostrate, to kiss the ground, to show abasement and allegiance. This word was used in Greek concerning two types of people- kings and gods. The Herod of Matthew fears the birth of Jesus as a threat to his political power. However, the Magi clearly see Jesus as more than an earthly king. The gift of gold is a testament to kingship in the material world. Traditionally the myrrh of the nativity is depicted as anointing oil, which is fitting to both anoint the King of Judea and the Messiah (the anointed one). The Shemen Ha-Mishchah of the Temple performed the same function. Frankincense is an incense offering for a deity and the purifier of sacred spaces. Matthew’s nativity scene drives home the concept of Jesus as a divinely anointed king in heaven and on earth through its sensorial imagery and strongly links that imagery to the Temple.

Interestingly, Luke’s nativity has none of this and is a decidedly humbler scene. There are no kingly gifts or prophetic dreams. Luke’s Jesus is born in a manger and attended by shepherds. These two seemingly contradictory versions of the nativity story show two philosophical worldviews in conversation at the time of the Christian bible’s codification.

The gospel of Matthew was written by a Greek-speaking second-generation Jewish Christian. He was probably writing for Greek-speaking Christians in Syria. His work is engulfed in the messianic fervour of the first century. Matthew’s gospels repeatedly emphasise that the Jewish nature of early Christianity should not be lost in a church becoming increasingly gentile. As such, he doesn’t explain Jewish tradition the way Mark does. He assumes his audience should know and conform to these customs. He is also writing in their sensory cultural language, grounding his writings in multiple systems of knowledge (i.e., scent, dreams, reason, witnessed events). Luke, on the other hand, is a slightly later writer. He was also writing to Greek-speaking Christians, but Luke was a gentile writing to an almost wholly Romanised gentile church, who were more familiar with Greek and Roman narrative forms.

Polycarp, a 2nd century Smyrnaean, and Nicholas, a 3rd century Myrian, were near contemporaries to the Gospel Matthew. At the time of his death, Polycarp was 86 years old. Irenaeus and Tertullian say that he had been a direct disciple of John the Apostle in his youth. By his death, Polycarp was probably the last living connection to the first generation of Christians. When Nicholas died at 76, he was perhaps one of the last connections to the second generation. They both lived long enough to see dramatic shifts in the demographics and theology of Christianity, but they were grounded in that earlier time. Their bodies did not exist as mere vessels for their souls but became living testaments to their faith and embodiments of scripture.

It is no surprise that the accounts of Polycarp and Nicholas echo the language, odours, anointing, and evocative imagery of Matthew’s nativity. Nor is it an accident that the nativity story itself was anchored in the sensorial experiences of the Temple. These were all attempts to embody the unknowable and ground the Christian Mythos into the olfactive culture from which the early Eastern Church emerged.

It was through both reason and embodied knowledge that Truth could be fully known.

Nuri McBride is a perfumer and writer, examining the cultural history of floral scent. She is the Program Curator for the Scent & Society lecture series at the Institute for Art and Olfaction

1 Wise, Elliot. (2009) “An ‘Odor of Sanctity’: the Iconography, Magic and ritual of Egyptian Incense”. Studia Antiqua. Vol 7. No. 1. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol7/iss1/8 ⤶

Plantings

A Voice for the Trees

By Mary Ellen Hannibal

The Real Cost of Planting Trees

By Lauren E. Oakes

Monet’s Garden in Giverny

By Gayil Nalls

The Hidden Warning of Fall Colors

By Brian Gallagher

Riveted by Nature’s Beauty

By Matsuo Bashō

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Roasted Cauliflower Snowflakes

By Ina Garten

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.