The Fragrance of the Soul: Olfaction, Power, and Death in Ancient Egyptian Religion

By Nuri McBride

Sign up for our monthly newsletter!

As a society, we have an anosmic view of history. We don’t think about how things smelt or what olfaction meant to people in the past because olfaction is not a primary consideration in the present. When we think of the scents of the past, it is with modern snobbishness and assurance that all those early primitive people could hardly smell anything over the miasma of pre-modern filth. Nothing could be further from the truth for the Ancient Egyptians, as evidenced by their writings, art, and tomb goods. While they suffered from the same stinks that plagued urban areas for aeons, they also adored and exonerated aromatics and strongly associated them with divinity and preserving the soul in the afterlife.

“Pure, pure is the Osiris, Great of the Five, master of seats, Sishou. The perfume, the perfume opens your mouth. It is the saliva of Horus, the perfume, it is the saliva of, {///} the perfume. It is what makes firm the heart of the two lords, the perfume.”

The tomb of Petosiris

Lefebvre, Gustave Le Tombeau de Petosiris, 1924, vol.1, p.131

The First Perfume Lovers

A lot of what we know about ancient Egyptians comes from their tombs, which has skewed popular concepts of the Egyptians as death-obsessed and morose. I think it is more accurate to say that the Egyptians were sensualists whose appreciation for life was informed by an acceptance of death, as well as a rich and developed concept of an afterlife. They filled their tombs with wooden scenes and sculptures depicting everyday life as well as the accruements of daily existence, not only for use in the afterlife but as a celebration of life itself. Perfume was a big part of that celebration.

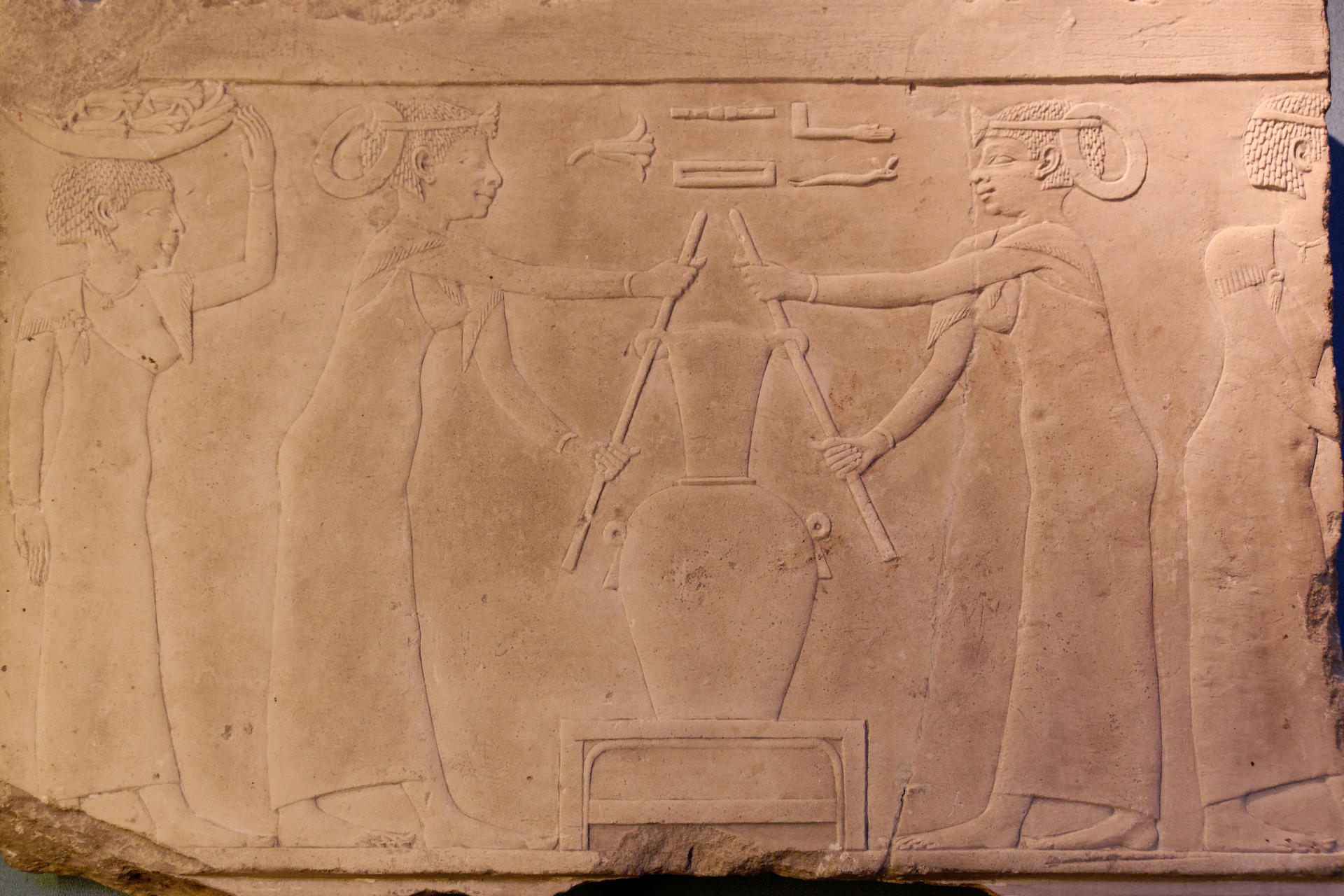

In later periods, when honouring one’s ancestors became a prominent practice, perfume was a common memorial offering. Perfuming equipment and perfume bottles were common grave goods for even those of modest means during the Ptolemaic Period. Descriptions of perfume-making, perfume application, and offering perfumed items to the gods are common motifs throughout Egyptian history in both temple and tomb art. In fact, an entire coded language in Egyptian art tells viewers what the subjects smelt like.

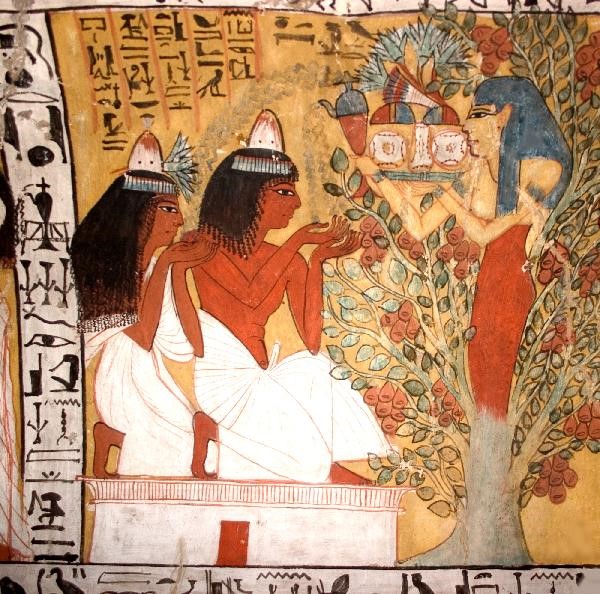

Let us look at the image of Sennedjem and his wife above. Hathor sprouts out of the Tree of Life, which in Egyptian art is a fig tree. Hathor is offering the food and waters of eternal life to the couple. Looks at what is just above the plate Hathor is holding. Those are four sacred Blue Lotuses and a Reed Flower, signifying that the items offered not only smell great but are, in fact, divine. As the scent of the Blue Lotus was considered holy and could consecrate divinity on things associated with it.

Also, look at Sennedjem and his wife; both are wearing perfumed wax cones on their heads. The cones have been freshly anointed with Myrrh; hence the reddish drips at the tops of the cones. Additionally, the wife’s cone has been pierced with a fragrant Blue Lotus, which may mean she pre-deceased her husband, or she just decided to throw an extra aromatic adornment on; it’s not completely clear. To an Egyptian audience, however, this would all be understood as information about the scent and spiritual state of the people present.

Temple of the Nose

It is important to remember that different cultures perceive and value olfaction differently than modern Western culture. I think we could learn a thing or two from societies that value olfaction. Ancient Egyptians lived for scent and understood their world through their noses. In their worldview, life came from breathing, and the breath of life was synonymous with the act of olfaction.

Egyptian writing is filled with allusions to scents, from talk of a lover’s sweet-smelling sigh to lengthy descriptions of the foulness of Ibis droppings in the summer sun. The ancient Egyptians’ vocabulary for odour and taste was more sophisticated than modern English, which must borrow words from other languages (like umami) to describe the sensory phenomenon when English isn’t sufficient. New Kingdom physicians identified 20 different scent categories and recognised that people often lost their sense of smell as they aged. They concluded that it was a sign that the Ba component of the Egyptian concept of the soul was already dissipating from the body.

Egyptian physicians were interested in the anatomy of the nose. Though they didn’t understand the olfactive process, they did know that the internal chambers played a part. The ancient Egyptian word for nose is fnd. From the Edward Smith Surgical Papyrus, we know that the area of the very back of the internal nose where the cribriform plate is located was called shtyt nd fnd. This has been translated since the 1950s as the inner chamber of the nose. However, shtyt is a word only used in a religious context, specifically in religious architecture, and means the dwelling place of the gods. So a better translation of shtyt nd fnd would be the nasal sanctuary.

Rene Schwaller de Lubicz argued that the layout of the original Luxor temple corresponds to a longitudinal dissection of the human head which would place the cribriform plate at the back wall of Room V, which was the Anointing Room. The place where the Pharaoh would be ritually made divine through the application of fragrances. Thereby embedding the anatomy of olfaction into sacred architecture. Schwaller goes on to state that additions to the temple system corresponded with other body parts, thereby making Luxor an anthropomorphic structure, a temple of man. I’ve yet to see conclusive data to back up Schwaller’s theory, but it is a fascinating idea. It should also be noted that Room V has been the Sanctuary to Alexander the Great since the Hellenistic invasion of Egypt. So even if earlier generations did intend this olfactive architecture, the use of Room V changed over time.

Hail, O Ye Gods Whose Odour Is Sweet

Olfaction and fragrance played a huge role in both political legitimacy and religious sanctity in Egypt. Take the below re-branding of the birth of Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut was born in a turbulent time. Her grandfather usurped the throne, and her brother/husband was only the third ruler of her dynasty. When he died young, she, as Queen, only had a daughter, her nephew by a co-wife was the only male heir. However, he was too young to rule. So, Hatshepsut became Queen Regent and eventually became sole Pharoah naming her nephew as her heir instead of co-ruler. In this unprecedented move, it was important for Hatshepsut to legitimise her reign, which she did, in part, by re-branding herself from the daughter of an upstart Pharaoh to the pleasant-smelling offspring of a god.

“He (Amun-Ra) found her (Hatshepsut’s mother) as she slept in the beauty of her palace. She waked at the fragrance of the god, which she smelled in the presence of his majesty. He went to her immediately, coivit cum ea (slept with her), he imposed his desire upon her, he caused that she should see him in his form of a god. When he came before her, she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty, his love passed into her limbs, which the fragrance of the god flooded; all his odours were from Punt.”

J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Two, § 196

The reference to Punt is essential. Early in her reign as Pharaoh, Hatshepsut commissioned an expedition to Punt and set up trade relations with the far-off kingdom. This was a huge diplomatic success for her, showing the power and reach of the Pharaoh. It was also an economic triumph and a fragrant one, as the primary goods brought back were frankincense, myrrh, and other aromatics materials. The aromatic symbolism of this rewritten birth and expedition would have been evident to her subjects. Pleasant smells signify holiness, and the King of the Gods smells like the fragrances from Punt. Punt is viewed as the ancient Egyptians’ ancestral homeland and Amun’s birthplace. Amun is the natural father of the Pharaoh, and he gave his divine and ancestral fragrances to the Pharaoh at conception. Pharaoh Hatshepsut reaffirmed this birthright by bringing the odours from Punt to Egypt and enriching the kingdom, so clearly, she had the divine right to rule.

A Perfumed Cosmology

As we see in the Ani Papyrus and Sennedjem’s tomb, olfaction played a role in Ancient Egyptian cosmology and the concept of the afterlife, partly because the Egyptians did not associate the senses with the body but rather with the vital spark or Ka. So, of course, one could taste, see, touch, and smell after death because the Ka did not die.

Ancient Egyptian religion emphasised creating order (Ma’at) out of chaos (Isfet). They saw Ma’at personified in the progression of time and seasonality of nature. Pleasant aromas from the natural world were synonymous with Ma’at and the gods. Foul odours weren’t seen as evil, more like disordered or unbalanced. Perhaps because of scent’s ephemeral nature, fragrance and the soul are often paralleled in Egyptian mythology.

The Book of the Dead, known to ancient Egyptians as the Book of Emerging Forth into the Light, was a collection of spells and guidance for the soul in the afterlife. It was a New Kingdom best seller based on the older Coffin and Pyramid Texts. While copies varied, most Books of the Dead included the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony, The 42 Negative Confessions, and the Weighing of the Heart. Along with spells to keep away all the beasties and baddies of Duat (the underworld). What is surprising is how often olfaction is alluded to in these ceremonies and spells.

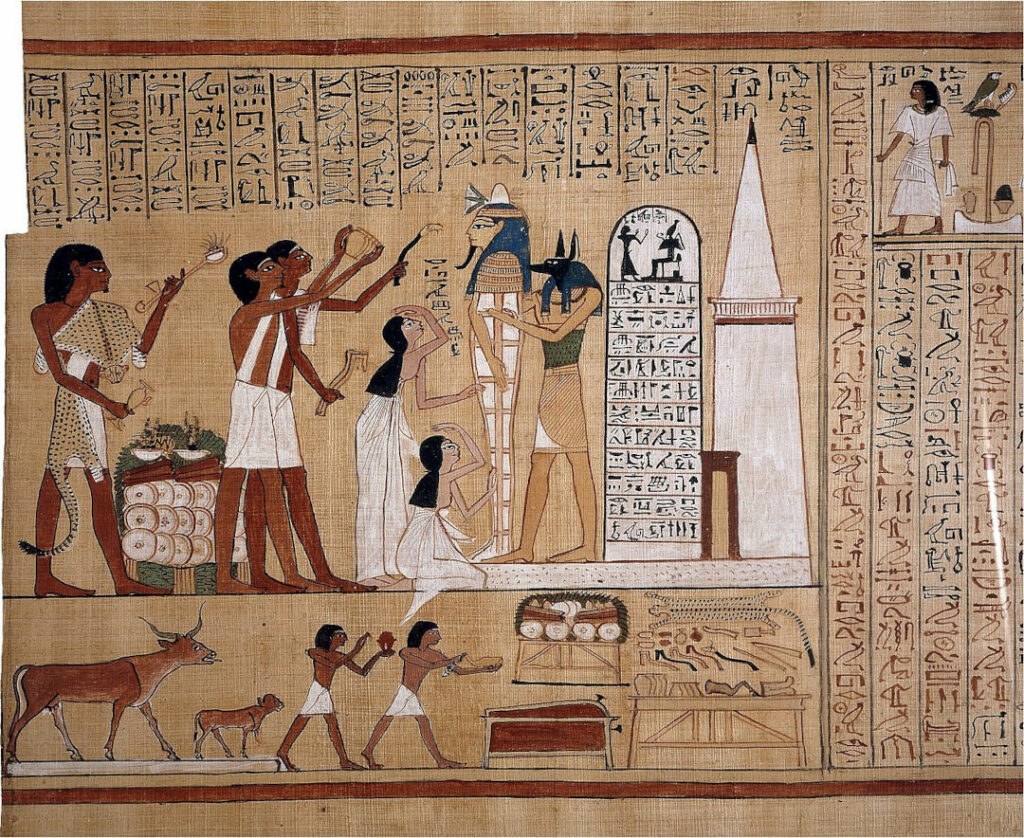

In the Ani Papyrus, the most extensive and intact Book of the Dead found, there is a feast of scent references. Ani, a new New Kingdom scribe, commissioned his beautifully decorated Book of the Dead to help guide him in the afterlife. In a treatise comprised of only 68 modern pages, the nose or nostrils are discussed six times. The burning, offering, or smelling of incense occurs 12 times. Six times the odour of the Blue Lotus is used to invoke holiness. The sweet-smelling breath of the gods has been alluded to 8 times. Discussion of the savoury smells of cooked meat happens four times. Fragrant unguents appear six times. Myrrh unguent is named explicitly as a needed item for performing the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony, which was a mandatory ritual for the dead to be able to continue into the afterlife. The Duat of the Ani Papyrus is a visually and olfactory magnificent place.

Instead of stating that the gods of the Duat bow before Osiris, it is phrased thusly:

“The Companies of the Gods praise thee, and the gods of the Duat smell the earth in paying homage to thee”

Ani Papyrus, approx. 1250 BCE Hymn of Osiris, E.A. Wallis Budge translation

More than just the descriptive landscape of the Book of the Dead, the gods recognise and evaluate human souls based on their smells. Here Anubis ushers Ani into the Hall of the 42 Judges and tells the judges he is a pretty good guy; after all, he smells godly.

“The god Anpu (Anubis) spake unto those about him with the words of a man who cometh from Ta-mera, saying, “He knoweth our roads and our towns. I am reconciled unto him. When I smell his odour it is even as the odour of one of you.”

Ani Papyrus, approx 1250 BCE, Chapter: Entering into the Hall of the Ma’ati to praise Osiris Khenti-Amenti, E.A. Wallis Budge translation

While most people couldn’t afford a custom-made book like Ani, these Books of the Dead were bought during a person’s lifetime, often with blank spaces in the spells to fill in with the owner’s name. They would have read over the scroll for years and committed it to memory.

Kyphi was burnt in every temple and most homes three times a day (morning, noon, and night). The Blue Lotus bloomed and perfumed the air every year after the inundation. Egyptians would have experienced these fragrances their whole lives. They would have associated them with Ma’at, divine cosmic order. The same order makes the Nile flood yearly and the sun travel across the sky daily. I like to think that these familiar odours, written about so frequently in the Book of the Dead, comforted those contemplating their deaths. Even in the world of jackal-headed gods and golden boats that flew in the sky, the kyphi still burned, and the Blue Lotus still bloomed.

We may never know for sure how the Egyptians felt about these smells. We do know that an ancient Egyptian would have understood their world through olfaction as much as any other sense, maybe even more so. Beyond the material world, they would have worried about the weight and scent of their souls in the afterlife.

Nuri McBride is a perfumer and writer, examining the cultural history of floral scent. She is the Program Curator for the Scent & Society lecture series at the Institute for Art and Olfaction.

Plantings

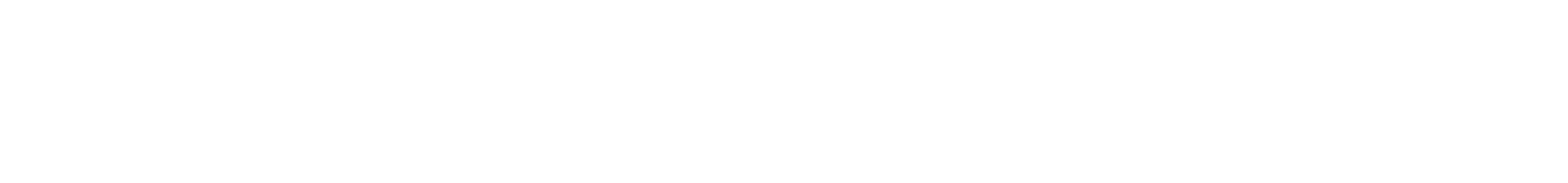

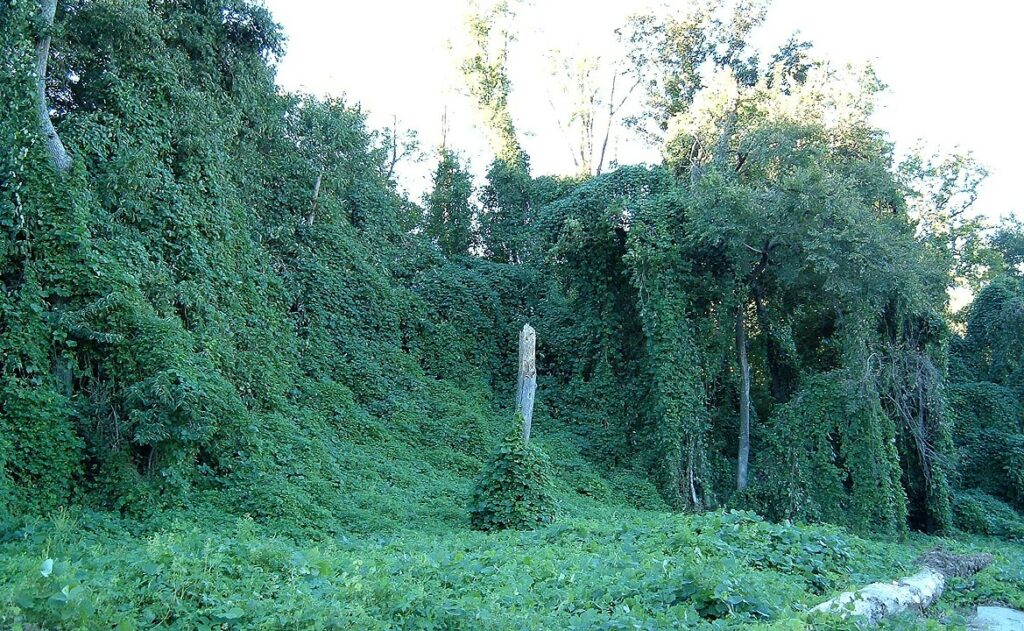

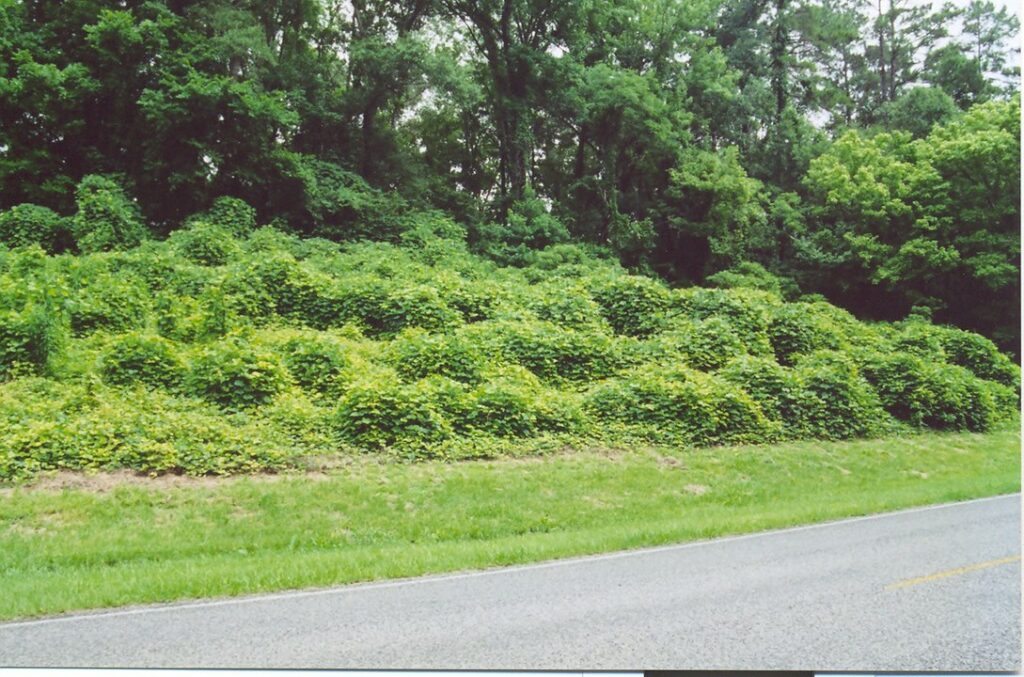

A Notorious Invasive Plant Shows Promise in Green Construction

By Tolu Olasoji

A Building Material That Consumes CO2 Has Finally Come to the US

By Peter Yeung

Australia’s Secret Rescue of Ancient Trees Offers an Insight Into Evolution

By Brian Gallagher

How are the Bees

By Lois Parshley

Robert Dash’s Madoo

By Gayil Nalls

Eat More Plants Recipes:

Pea Coffee

As Ireland transitions from the rich, smoky scent of peat-burning to a more sustainable future, its olfactory heritage is evolving. What will become the next iconic aromatic symbol of Ireland?

Click to watch the documentary trailer.